Bharhut

| Author: Laxman Burdak IFS (R) |

Bharhut (भरहुत) is a village in Satna district of Madhya Pradesh, Central India, known for its famous Buddhist stupa. Bharhut stupa is one of the earliest extant Buddhist structures and due to the presence of dedicatory inscriptions, it was patronized by almost exclusively by monks, nuns and the non-elite laity. The Bharhut stupa may have been established by the Maurya king Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE, but many works of art were apparently added during the Sunga period, with many friezes from the 2nd century BCE. An epigraph on the gateway mention its erection "during the supremacy of the Sungas"[1] by Vatsiputra Dhanabhuti[2].

Location

Geographic coordinates: 24°26′49″N 80°50′46″E / 24.446891°N 80.846041°E

Bharhut is located at the head of the narrow Mahiyar valley in central India, 200 miles northwest of Sanchi, where the ancient trade route from the western coastal regions to the eastern metropolis of Pataliputra joined the road to northern Sravasti. The Bharhut developed during second century AD which was the last phase of Mauryan dynasty. Bharhut is the name of hill seen behind the stupa site. Besides Bharhut hill is situated the Nairo hill, which has a flat top (plateau) having traces of an ancient fort. The constructions of Bharhut consist of red stones obtained from Nairo hill and Bharhut hill. [3]

Variants of name

- Barhut (बरहुत)

- Bagud (Alexander Cunningham)

- Balsevati (Prasenjit's purohit in the book 'Bavri')

- Bardawati /Bardavati (Bardadeeh village , situated 2 miles north of Satna, MP)

- Bardaotis (Ptolemy in his 'Geography')

- Bhar-Bhukti/Bharbhukti ('the country of Bhars'. Bharbhukti later changed to Bharhut)[4]

- Bharhat (T.W. Rhys Davids)

- Vardavati (ancient name)

- Vardavati Nagar

Origin

The place gets name Bharhut after its rulers of clan Bhar or Rajbhar. It became Bharhut over a period of time.[5] Bharhut was located on route from Kosambi, the capital of Vatsa Janapada to Vidisha, the capital of Dasharna janapada.[6] On this very route is situated another important ancient Buddhist stupa of Deur Kothar discovered very recently, which is 140 kms away from Bharhut in northeast direction in Rewa district. The origin of the word 'Bharhut' would have been from 'Bhar-Bhukti', which means 'the country of Bhars'. Bharbhukti later changed to Bharhut. [7]

Bhar is the Jat clan found in Districtt Hisar (villages-Singhwa Khas) in Haryana. They are also in Punjab who were originally from Rajasthan. In Rajasthan they are found in Tonk distrct (villages-Raghunathpura Parli). Similarly Bharshiv, derived from Bhar, is also a Jat gotra originated from Nagavansh[8] Bhar clan Jats are found in Multan area in Pakistan. [9],[10]

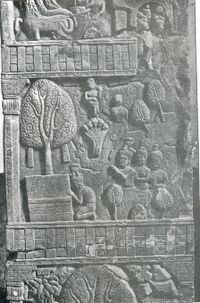

T.W. Rhys Davids writes that Bharhat and Bharhut both names are correct but Bharhat is more correct. He has mentioned both the names in his book. [11] He writes that plate 13 of Bharhut stupa depicts Raja Prasenjita 600 BCE on a chariot with 24 spiked Dhamma Chakra of Buddha. [12] This shows that Raja Prasenjit was not only the follower of Buddhism but had also adopted Buddha's Dhamma Chakra as state symbol. [13]

The ancient name of Bharhut was Vardavati. Ptolemy in his 'Geography' has mentioned a city named 'Bardaotis' situated on the route from Ujjain to Pataliputra, which according to Alexander Cunningham is related with Bharhut. According to Tibetan 'Dhulva' a Shakya monk named Samyak was expelled from Kapilavastu and came to Bagud and built a stupa here. Alexander Cunningham tells us that Bagud is Bharhut. It has been mentioned to be within the Ātavī province of the ancient literature. Samudragupta has mentioned Atavi in the list of places won by him. KP Jayaswal has identified Atavi with Bundelkhand and eastern Baghelkhand. [14]

Vardavati was a very prosperous town in ancient times and it was one of important centres of trade. The Koshambi ruler, Prasenjit's purohit has mentioned in the book 'Bavri', about this city as 'Balsevati'. A. Cunningham also supports this view. In samvat 197 (140 AD) the Bharshiv people became ruler of this region and renamed it as 'Bharbhukti' after them. The 'Bardadeeh' village , situated 2 miles north of Satna city, gets the name from Bardavati. Deeh means the abondoned place. [15]

History

As per Balmiki Ramayana this region was under the influence of Sutikshana Muni. The region was known as Dandakaranya and mentioned later in Koshala Kingdom. During Mahabharata period Kārūpā tribe ruled here. According to Pali literature this region was part of Majjhima Province. Tibetan literature 'Dhulva' tells us that when Buddha visited Kapilvastu he gave his hair and nails to one Shakya named Samyak and sent him to 'Bagud' province. At that time this region was part of Vatsa Janapada. Shakya Samyak came and stayed at place called Vardavati Nagar. This ancient city was near 'Naro Pahar' and 'Bharhut Parvat'. The region was ruled by Mauryas, Shungas, Nagas, Bharashivas, Vakatakas, Guptas, Kalachuris, and Chandelas.[16]

In the last phase of Mauryan rule there were many janapada states in India. In Madhya Pradesh there were seven cities namely - Tripuri, Eran, Mahishmati, Bhagil, Vidisha, Ujjayani and Padmavati which were important centres of Mauryan rulers and Buddhists. [17] There are large number of archaeological sources scattered around in these areas about these sites.

The Naga dynasty had its hold in the present Gwalior - Bhopal divisions of Madhya Pradesh from about beginning of third to the middle of fourth century AD. Their centres were at Padmavati (Pawaiya near Gwalior) and Kantipuri (Kutwār district Morena ). Several thousand copper coins have been discovered at these sites and other sites. The successors of Satvahanas in the Tripuri region were Bodhis. Names of five Bodhi rulers are known from the recent excavations at Tripuri. [18] Eran can be called to be the oldest historical town of Sagar district in Madhya Pradesh. In earlier coins and inscriptions its name appears as Airikiṇa. From an early inscription at Sanchi we know that the residents of Eran had made some gifts to the famous Stupa situated there. The word erakā probably refers to a kind of grass which grows at Eran in abundance. [19]

Cunningham writes that it seems probable, however, from the long inscription on the East Gateway of the Bharhut Stupa that the Stupa itself was situated "in the kingdom of Sugana " (Sugana raje). At a later date we know that it must have belonged to the wide dominions of the Gupta dynasty, whose inscriptions have been found at Garhwa, Eran, and Udayagiri. During the rule of that powerful family, the country around Bharhut would seem to have fallen into the hands of petty chiefs, as a number of copper-plate inscriptions have been found within 12 miles of the Stupa referring to two different families who were content with the simple title of Maharaja. These inscriptions range in date from 156 to 214 of the era of the Guptas, or from A.D. 350 to 408.[20]

Somewhat more than two centuries ater Bharhut was under Harsha Vardhana of Kanoj as lord paramount, but it is almost certain that the district had also a petty chief of its own. After the death of Harsha the Baghels and Chandels rose to power, the former ruling in Bandhogarh, the latter in Khajuraho, Mahoba, and Kalinjjar. [21]

Probable age of the Stupa of Bharhut

The probable age of the Stupa which Cunningham has assigned to the Asoka period or somewhere between 250 and 200 B.C. Bharhut was on the high road between Ujjain and Bhilsa in the south, and Kosambi and Sravasti in the north, as well as Pataliputra in the east. On this line at a place called Rupnath, only 60 miles from Bharhut, there is a rock inscription of Asoka himself. As he was governor of Ujjain during his father's lifetime Asoka must often have passed along this road, on which it seems only natural to find the Stupas of Bhilsa, the rock inscription of Rupnath, the Stupa of Bharhut, and the Pillar of Prayaga or Allahabad ; of which two are actual records of his own, while the inscriptions on the Railings of the Stupas show that they also must belong to his age.

The inscription of Raja Dhanabhuti, the munificent donor of the East Gateway of the Stupa — and most probably of the other three Gateways also. In his inscription he calls himself the Raja of Sugana, which is most likely intended for Sughna or Srughna, an extensive kingdom on the upper Jumna. I have identified the capital of Srughna, with the modern village of Sugh which is situated in a bend of the old bed of the Jumna, close to the large town of Buriya. Old coins are found on this site in considerable numbers. In this inscription on the East Gateway at Bharhut Raja Dhanabhuti calls himself the son of Aga Raja and the grandson of Viswa Deva, and in one of the Rail-bar inscriptions we find that Dhanabhuti's son was named Vādha Pala. Now the name of Dhanabhuti occurs in one of the early Mathura inscriptions which has been removed to Aligarh. The stone was originally a corner pillar of an enclosure with, sockets for rails on two adjacent faces, and sculptures on the other two faces. The sculpture on the uninjured face represents Prince Siddhartha leaving Kapilavastu on his horse Kanthapa, whose feet are upheld by four Yakshas to prevent the clatter of their hoofs from awakening the guards. On the adjacent side is the inscription placed above a Buddhist Railing. At some subsequent period the Pillar was pierced with larger holes to receive a set of Rail-bars on the inscription face. One of these holes has been cut through the three upper lines of the inscription, but as a few letters still remain on each side of the hole it seems possible to restore some of the missing letters. We read the inscription as follows :

1. Kapa (Dhana)

2. Bhutisa * * * Vatsi

3. Putrasa (Vadha Pa) lasa

4. Dhanabhutisa dānam Vedika

5. Torana cha Ratnagraha sa —

6. -va Buddha pujāye sahā māta pi-

7. -tā ki sahā* chatuha parishāhi.

There can be little doubt that this inscription refers to the family of Dhanabhuti of Bharhut, as the name of Vātsi putra of the Mathura pillar is the Sanskrit form of the Vāchhi putra of the Bharhut Pillar. This identification is further confirmed by the restoration of the name of Vādha Pāla, which exactly fits the vacant space in the third line. From this record, therefore, we obtain another name of the same royal family in Dhanabhuti II., the son of Vadha Pala, and . grandson of Dhanabhuti I. Now in this inscription all the letters have got the matras, or heads, which are found in the legends of the silver coins of Amoghabhuti, Dara Grhosha, and Varmmika. The inscription cannot, therefore, so far as we at present know, be dated earlier than B.C. 150. Allowing 30 years to a generation, the following will be the approximate dates of the royal family of Srughna :

- B.C. 300. Viswa Deva.

- B.C. 270, Aga Raja.

- B.C. 240. Dhanabhuti I.

- B.C. 210. Vadha Pala.

- B.C. 180. Dhanabhuti II.

- B.C.150. -------------

Now we learn from Vadha Pala's inscription, Plate LVI., No. 54, that he was only a Prince (Kumara) the son of the Baja Dhanabhuti, when the Railing of the Bharhut Stupa was set up. We thus arrive at the same date of 240 to 210 B.C. as that previously obtained for the erection of the magnificent Gateways and Railing of the Bharhut Stupa. To a later member of this family I would ascribe the well-known coins of Raja Amogha-bhuti, King of the Kunindas, which are found most plentifully along the upper Jumma, in the actual country of Srughna. His date, as I have already shown, must be about B.C. 150, and he will therefore follow immediately after Dhana-bhuti II. I possess also two coins of Raja Bala-bhuti, who was most probably a later member of the same dynasty. But besides these I have lately obtained two copper pieces of Aga Raja, the father of Dhana-bhuti I. One of these was found at Sugh, the old capital of Srughna, and the other at the famous city of Kosambi, about 100 miles to the north of Bharhut.

I may mention here that my reading of the name of the Kunindas on the coins of Amogha-bhuti was made more than ten years ago in London, where I fortunately obtained a very fine specimen of his silver mintage. This reading was published in the "Academy," 21st November 1874. I have since identified the Kunindas, or Kulindas, as the name is also written, with the people of Kulindrime, a district which Ptolemy places between the upper courses of the Bipasis and Ganges. They are now represented by the Kunets, who form nearly two-thirds of the population of the hill tracts between the Bias and Tons Rivers. The name of Kunawar is derived from them ; but there can be little doubt that Kunawar must once have included the whole of Ptolemy's Kulindrine as the Kunets now number nearly 400,000 persons, or rather more than sixty per cent, of the whole population between the Bias and Tons Rivers. They form 58 per cent, in Kullu ; 67 per cent, in the states round about Simla, and 62 per cent, in Kunawar. They are very numerous in Sirmor and Bisahar, and there are still considerable numbers of them below the hills, in the districts of Ambala, Karnal, and Ludiana, with a sprinkling in Delhi and Hushiarpur.

Note - This section is from The stūpa of Bharhut: a Buddhist monument ornamented with numerous sculptures by Alexander Cunningham 1879, pp.14-17

Bharhut stupa

The Bharhut stupa (now dismantled and reassembled at Kolkata Museum) contains numerous birth stories of the Buddha's previous lives, or Jataka tales. Many of them are in the shape of large, round medallions. In conformity with the early aniconic phase of Buddhist art, the Buddha is only represented through symbols, such as the Dharmachakra, the Bodhi tree, an empty seat, footprints, or the triratana symbol. The style is generally flat (no sculptures in the round), and all characters are depicted wearing the Indian dhoti, except for one foreigner, thought to be an Indo-Greek soldier, with Buddhist symbolism.

An unusual feature of Bharhut panels is inclusion of text in the narrative panels, often identifying the individuals.

All the archaeological objects from the stupa have been moved to the Calcutta's Indian Museum.[22] No antiquities exist at Bharhut now. Some antiquities were sent to Allahabad museum and some are preserved at Ramavana museum in Satna district.

General Cunningham had visited this area in 1873 on way to Nagpur. He was fascinated to find such a heritage site but at the same time pained at its ignorance by the people and the government. He left some guards behind to look after the site and came back in February 1874. He collected the scattered pieces of sculptures and records and tried to understand its design and lay out. He came third time in November 1874 with some legal rights. He carried some of the sculptures to Kolkata and started a Bharhut gallery in the National Museum. After a detailed study of Buddhist literature and the sculptures from the site, he published in 1876 a book titled "The Stupa of Bharhut", which is still an authentic book about the Bhahut stupa.

The famous 8 Buddhist stupas have been built on the relics of Buddha in his honour. Bharhut is not in that list. It is still not clear about on whose relics this stupa is built. General Cunningham had found in 1874 excavations a small box carrying the "Rakh Phool (ashes)" , which could not be identified but he handed it over to the Raja of Nagaud for safe custody. [23]

The Barhut stupa is an example of people's contribution in building the stupa. The construction of this stupa was a slow process. It took decades to come to the final shape. It was started by the Mauryan ruler Ashoka, later it was completed by the contributions from the followers of Buddhism, who visited this place and their names are inscribed as donors. The construction continued from first century B C to first century A D. [24]

In the days of Mauryan Emperor Asoka (c. 272-234 BC) a brick stupa measuring about 68 feet in diameter and covered with plaster was constructed at Bharhut. During the reign of the Sungas, who were in power in the second century BC and reigned until the year 72 BC, a richly decorated stone railing, 88 feet in diameter, was added to enclose the mound. Nothing is now visible of the celebrated stupa at this Buddhist site other than a shallow depression in the ground. Bricks and sandstone fragments are strewn all around. The remains of the sandstone railing pillar and gateways that surrounded the stupa have all been removed. They are mostly displayed in the Bharhut gallery at the Indian Museum, Calcutta. [25]

Bharhut is famous for the ruins of a Buddhist stupa (shrine) discovered there by Major General Alexander Cunningham in 1873. The stupa's sculptural remains are now mainly preserved in the Indian Museum, Calcutta, and in the Municipal Museum of Allahabad. The stupa was probably begun in the time of Asoka (c. 250 BC). It was originally built of brick, and it was enlarged during the 2nd century BC, when a surrounding stone railing with entrances on the four cardinal points was constructed. This railing bears a wealth of fine relief carving on its inner face. Around the beginning of the 1st century BC four stone gateways (toranas), each elaborately carved, were added to the entrances. An inscription on these gateways assigns the work to King Dhanabhuti in the rule of the Sungas (i.e., before 72 BC). The sculptures adorning the shrine are among the earliest and finest examples of the developing style of Buddhist art in India. [26]

Decline of Bharhut

Following the Mauryans, the first Brahmin king was Pusyamitra Sunga, who is frequently linked in tradition with the persecution of Buddhists and a resurgence of Brahmanism that forced Buddhism outwards to Kashmir, Gandhara and Bactria.[27] According to the 2nd century Ashokavadana:

- "Then King Pusyamitra equipped a fourfold army, and intending to destroy the Buddhist religion, he went to the Kukkutarama. (...) Pusyamitra therefore destroyed the sangharama, killed the monks there, and departed. After some time, he arrived in Sakala, and proclaimed that he would give a hundred dinara reward to whomever brought him the head of a Buddhist monk" [28]

Later Sunga kings were seen as amenable to Buddhism and as having contributed to the building of the stupa at Bharhut.[29] Brahmanism competed in political and spiritual realm with Buddhism in the gangetic plains. Buddhism flourished in the realms of the Bactrian kings. [30]

With the decline of Buddhism in India, the number of visitors to Bharhut came down and so was the funding for its maintenance. With the changed situations the opposition to Buddhism increased and people forgot its importance. People used the decayed material from the stupa for the construction of temples of their deities. The glory of the stupa was lost. When Nagaud state was founded about 700 years back, the local people collected material from stupa to establish new villages and used in construction of wells, bawdis and fortresses. Some material of stupa was collected from the fortress of Bhatnawra about 40 years back. [31] With the decline of Buddhism, it started the decline of Bharhut stupa also. The stupa was completely destroyed over a period of about one thousand years. There were attempts to transform the stupa to a Hindu place of worship. It was converted in to a Shiva temple after assembling the ruins and reconstruction. The name of Bharhut village also changed to Bhairopur in 10th century[32]. During 12 century some local ruler named Ballaldeva put his inscription. Later during Mugal rule and the British rule the villagers took away the stone pillars to construct wells, houses etc. These were used by the contractors in the construction of Maihar-Satna Railway line bridges and in the Satna-Maihar road construction.

Vehicles at Bharhut

Alexander Cunningham found at Bharhut that the only vehicles which were observed amongst all the varied scenes of Bharhut Sculptures are the Boats, the horse chariots, and the bullock cart. Of the boat there are two examples, but unfortunately they are both in the same bas-relief, and that still lies buried under the walls of the palace at Uchhahara in Satna district. Of the horse chariots there are also two examples. One is the royal chariot of Raja Prasenjit, having two-wheels, holds four people including Raja Prasenjit and is drawn by horses. The other chariot occurs in the Mygapaka Jataka. It is empty but is exactly the same with the last, with the same four horses. Of the bullock cart there are likewise two specimens. One in the bas-relief of the Jetavana monastry and the other filling the whole of the medallion of the rail-bars.[33]

The sculptures at Bharhut

Alexander Cunningham has compiled information about Sculptures found at Bharhut and published in his book - "The Stupa of Bhahut". Some of the figures could not be interpreted by him. Some which have been understood are as under:

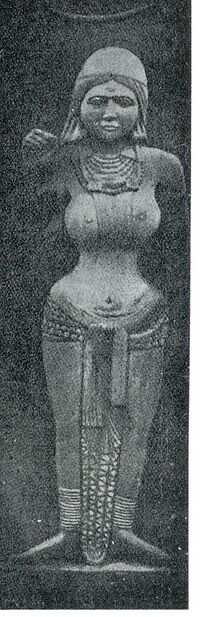

The Yakshas at Bharhut

The Yakshas - The most striking of all the representations of the demigods are the almost life-size figures of no less than six Yakshas and Yakshmis, which stand out boldly from the faces of the corner pillars at the different entrances to the Courtyard of the Stupa. According to the Buddhist cosmogony the palace of Dhritarashtra and the Gandharvas occupies the East side of the Yugandhara rocks, that of Virudha and the Kumbhandas the South, that of Virupaksha and the Nagas the West, and that of Vaisravan and his Yakshas the North. Two of these guardian demigods I have been able to identify with two of the Yakshas figured on the entrance pillars'of the Bharhut Stupa. The Pali name Waisrawana, in Sanskrit Vaisravana, is a patronymic of Kuvera, the king of all the Yakshas, whose father was Visravas. To him was assigned the guardianship of the Northern quarter; and accordingly I find that one of the figures sculptured on the comer pillar of the Northern Gate at Bharhut is duly inscribed Kupiro Yakho, or Kuvera Yaksha. To Virudhaka was entrusted the guardianship of the South quarter, and accordingly the image of Virudako Yakho is duly sculptured on the corner pillar of the South Gate. With Kupiro on the North are associated Ajakalako Yakho and Chada Yakhi, or Chanda Yakshini; and with Virudaka on the South are associated Gangito Yakho and Chakavako Naga Raja. The West side was assigned to Virupaksha; but here I find only Suchiloma Yakho and Sirima Devata on one pillar, and on a second the figure of Supāvaso Yakho. Dhritarashtra was the guardian of the East side ; but unfortunately the two corner pillars of this Gate have disappeared. There is, however, in a field to the west of the Stupa a corner pillar bearing the figure of the Yakshini Sudasava, which could only have belonged to the Eastern Gate. We have thus still left no less than six figures of Yakshas and two of Yakshinis, which are most probably only about one-half of the number which originally decorated the Bharhut Railing. I may note here that the corner pillar of the Buddhist Railing which once surrounded the Great Temple at Bauddha Gaya bears a tall figure of a Yakshini on one of the outward faces as at Bharhut.

The Yakshas were the subjects of Kuvera, the guardian of the North quarter of Mount Meru, and the God of Riches. They had superhuman power, and were universally feared, as they were generally believed to be fond of devouriiag human beings. This must certainly have been the belief of the early Buddhists, as the legend of the Apannaka Jataka is founded on the escape of Buddha, who was then a wise merchant, from the snares of a treacherous Yaksha, while another merchant who had preceded him in the same route had been devoured with all his followers, men and oxen, by the Yakshas, who left " nothing but their bones." I suspect that this belief must have originated simply in the derivation of their name Yaksha, " to eat", for there is nothing ferocious or even severe in the aspects of the Yakshas of the Bharhut sculptures. These must, however, have been considered as friendly Yakshas, to whom was entrusted the guardianship of the Four Gates of the Stupa. The ancient dread of their power has survived to the present day, as the people of Ceylon still try " to overcome their malignity by Chaunts and Charms. I think it probable also that the Jak Deo of Kunawar and Simla may derive its name from the ancient Yaksha or Jakh.

Of Kuvera, the king of the Yakshas, there is frequent mention in the Buddhist books under his patronymic of Wessawano or Vaisravana, as on attendant an Buddha along with the guardian chiefs of the other three quarters.

Regarding the general appearance of the Yakshas we are told that they resembled mortal men and women. That this was the popular belief is clearly shown by the wellknown story of Sakya Sinha's first appearance at Rajagriha as an ascetic. The people wondered who he could be. Some took him for Brahma, some for Indra, and some for Vaisravana. This is confirmed by the figures of the Yakshas and Yakshinis in the Bharhut Sculptures, which in no way differ from human beings either in appearance or in dress. In the Lalita Vistara also Vaisravana is enumerated as one of the chiefs of the Kāmāvachara Devaloka, of which all the inhabitants were subject to sensual enjoyments.

Note - This section is from The stūpa of Bharhut: a Buddhist monument ornamented with numerous sculptures by Alexander Cunningham 1879, pp.19-20

The sculptures of following named Yakshas have been found at Bharhut:

- Vaisravana i.e. Kuvera, the king of Yakshas - On the northern gateway at Bharhut Stupa. The character of Vaiśravaṇa is founded upon the Hindu deity Kubera. Vaiśravaṇa (Sanskrit वैश्रवण) or Vessavaṇa (Pāli वेस्सवण,Sinhala වෛශ්රවණ) also known as Jambhala, is the name of the chief of the Four Heavenly Kings and an important figure in Buddhist mythology. Vaiśravaṇa is the guardian of the northern direction, and his home is in the northern quadrant of the topmost tier of the lower half of Mount Sumeru. He is the leader of all the yakṣas who dwell on the Sumeru's slopes. Bhedaghat is a place of tourist importance near Jabalpur city in Madhya Pradesh on the banks of River Narmada. The banks of river Narmada is described as the birth place of Yaksha king Kuvera (Vaisravana), where his father Visravas, who was a sage, lived (MBh 3,89). King Vaisravana or Kubera was the ruler of Lanka Kingdom which was guarded by hosts of Rakshasas.

- Virudhaka - Who was son of Raja Prasenjit and king of Kashi. This king is probably related with Burdak gotra of Jats.

- Ajakalako - The word Ajakalako cosists of Aja+Kalaka. Ajmedia (अजमेदिया) jat gotra gets its name from Raja Aja (अज). Kalaka is a name of Asura mentioned with Pannagas in Vana Parva, Mahabharata/Book III Chapter 170 verse 2 like this: थरुमै रत्नमयैश चैत्रैर भास्वरैश च पतत्रिभिः, पौलॊमैः कालकेयैश च नित्यहृष्टैर अधिष्ठितम. Ajakalako (Ajakalaka or Ajakalāpaka) can be associated with a specific shrine. In particular, Ajakalāpaka is mentioned in Udana as being a resident of town Pātali.[34]

- Gangito

- Suchiloma Yakho - It is believed, the Buddha met and conversed with evil spirit, Suchiloma. Reference regarding Suchiloma can be found in Sutta Nipata, discourse No 5. Suchiloma, the demon thug was won over to learn teaching is very remarkable instance. It reasserts how the Buddha used his knowledge of psychology as a supreme teaching. Once the Buddha was staying in Gaya in the residence of demon Suchiloma. The demon saw the Buddha and made his way near him. Having come closer, Suchiloma pressed his body against the Buddha and He bent his body away. Then Suchiloma asked the Buddha, “Monk, do you fear me?” The Buddha replied, “No, sir, I fear you not, though your touch be unpleasant.” This unusual encounter eventually gave rise to a remarkable conversation on the nature human emotions and their origins. (Sn. Suchiloma Sutta).

- Purnaka Yaksha - The Yaksha named Pūrṇaka is the same name as that of Yaksha depicted in narrative reliefs is listed in the Mahamayupuri as being associated with the town Malaya. [35] Malaya (मलया) Malya (मलया) is ancient gotra of Jats who live in Tonk district (in villages Bagadi and Ganeshpura) in Rajasthan.

- Dhritarashtra - Dhritarashtra (धृतराष्ट्र) was a Nagavanshi ruler. Dhetarwal (धेतरवाल) gotra of Jats are descendant of this mahapurusha Dhritarashtra (धृतराष्ट्र) of Nagavansh.[36]

- The Yakshinis

- Chanda Yakshini - At northern gateway

- Sudasava Yakshini -

- Sudarsana Yakshini - Who is shown as riding Makara. This pillar was donated by Kanaka (कनक). [37] The Sudasana on Bharhut pillar inscription is most likely the same as Sudarshana mentioned in the Mahāmāyūpuri as being the tutelery deity of the town Champa. [38]

The Jat historian Hukum Singh Panwar (Pauria)[39] writes that Jakhar is derived from Yaksha. This tribe Jakhar claim Jakha or Jakhu, known as Yaksha or Yakshu in Sanskrit, to be their most ancient eponymous progenitor. [40][41] The Jakha and Jakhaudiya gotra are also derived from Yaksha.

The Devas at Bharhut

- The Devas

- Sirima Devta (Bhumata) - The mother goddess

- Chulakoko Devta - Chulakoko Devta on southern gateway is shown standing on elephant catching a branch of tree with one hand. The name of donar inscribed is Dharma Gupta. [42] It is probably connected with Chalka gotra of Jats. There are two such inscription in Hathigumpha inscriptions

The Nagas at Bharhut

In the history of Buddhism the Nagas play even a more important part than the Yakshas. One of their chiefs named Virupaksha was the guardian of the Western quarter.

Like the Yakshas the Nagas occupied a world of their own, called Nagaloka, which was placed amidst the waters of this world, immediately beneath the three-peaked hill of Trikuta, which supported Mount Meru. The word Naga means either a " snake " or an " elephant," and is said to be derived from Naga, which means both a " mountain " and a " tree." In the Puranas the Nagas are made the offspring of Kasyapa by Kadru. In Manu and in the Mahabharata they form one of the creations of the seven great Rishis, who are the progenitors of all the semi-divine beings such as Yakshas, Devas, Nagas, and Apsarases, as well as of the human race. The capital of the Nagas, which was beneath the waters, was named Bhogawati, or the " city of enjoyment." Water was the element of the Nagas, as Earth was that of the Yakshas ; and the lake-covered land of Kashmir was their especial province. Every spring, every pool, and every lake had its own Naga, and even now nearly every spring or river source bears the name of some Naga, as Vir Nag, Anant Nag, etc., the word being used as equivalent to a " spring or fount of water."

Even a bath, was sufficient for a Naga as we learn from the story of the birth of Durlabha the founder of the Karkotaka, or Naga dynasty of Kashmir Rajas in A.D. 625.

In Buddhist history the Naga chiefs who are brought into frequent contact with Buddha himself, are generally connected with water.

Thus Apalāla was the Naga of the lake at the source of the Subhavastu, and Elāpatra was the Naga of the well-known springs at the present Hasan Abdāl, while Muchalinda was the Naga of a tank on the south side of the Bodhi tree at Uruvilwa, the present Bauddha Gaya. At Ahichhatra also there was a Nāga Raja who dwelt in a tank outside the town, which is still called Ahi-Sāgar or the " serpent's tank," as well as Adi-Sāgar, or " king Adi's tank." The connection of the Nagas with water is further shown by their supposed power of producing rain, which was possessed both by Elapatra and by the Naga of Sankisa, and more especially by the great Nāga Raja of the Ocean, named Sagara, who had full power over the rains of heaven. In the Vedas also the foes of Indra, or watery clouds, which obscure the face of the sky, are named Ahi and Vritra, both of which names are also terms for a snake. The connection of the Nagas with water would therefore seem to be certain, whatever may be the origin of their name.

In the Bharhut sculptures there are several Naga subjects, all very curious and interesting, of which the principal are the Trikutaha Chakra, and the conversion of Elapatra Naga.

Note - This section is from The stūpa of Bharhut: a Buddhist monument ornamented with numerous sculptures by Alexander Cunningham 1879, pp.23-25

- The Nagas

- Chakavako Nagaraja - Chakavako or Chakavaka Nagaraja Under trikuta (Meru Parvat), Bhogawati capital

- Apalana Naga

- Elapatra Naga - Naga Erapatra is described in both Mahavastu and Dhammapada commentaries as being a resident of a lake in Takshashila. [43]

- Muchlinda Naga (Blind)

- Sagara

- Kalika Nagaraja - Kalika is progenitor of Jat clan khatkal. 'Kata Kalika' became 'Katkal' or Khatkal.

- Nandopananda Naga king - Shalya Parva, Mahabharata/Book IX Chapter 44 mentions about this king. पुत्र मेषः परवाहश च तदा नन्दॊपनन्दकौ, धूम्रः शवेतः कलिङ्गश च सिद्धार्दॊ वरदस तदा (Mahabharata:IX.44.59)

- The Apsaras - The following apsaras have been shown dancing with their names inscribed:

- Urvasi

- Menaka

- Misrakesi

- Alambusha

- Subhadra

- Sudasana

- The human beings - Royal personage

- Rama

- Janaka Raja

- Sivala Devi

- Raja Prasenjit

- Ajatasatru

- Royal Princes Maya Devi

- Vipachitta Asura - There is no battle scene but a single figure of a soldier is available. His costume is tunic with long sleeves, cords, dhoti, boots, swords, belt, weared Omega (Tri-rtna). The warrior is having a grape climber in right hand. According to 'Sanyukta nikaya' Buddhist grantha this figure is of Vipachitta Asura. Barua considers it Surya devta. [44]

- Shalabhanjika - This sculpture of Shalabhanjika from Bahrhut, of the period c.100 BC, is at Indian Museum Kolkata. Here Shalabhanjika is grasping the tree in time honoured pose, one of several from Bharhut. The Yakshi who grasps, kicks, or twines herself around a tree is a symbol of fruitfulness, like the dryads of ancient Greek mythology, and a similar pose is often used in scenes of Maya giving birth to the Buddha, who emerges from her side.

It would seem, then, that these spirit-deities have been collected fron through out the subcontinent in order to be displayed on the rails and gateways of this early Buddhist monument.[45]

The costumes

Both male and female wear small cloth below the waste. The males wear cloth utariya on upper part of the body but females wear only ornaments. Females put a light muslin wrapper on the face but face is visible. The female dresses and ornaments include necklaces, collars, gridles (Mekhala), dhoti, veils, keep hair parted in middle, scarf, laltika (bindi of eight types), earrings (kundals), jhumka, tri-ratna, i.e. Buddhist triads (Buddha, Dhamma, Sangha), armlets (bracelets), anklets, thumb rings, finger rings mostly wear female and male both. The Royal and lay costume include dhoti, veils, (chaddar), muslin worked with gold and precious stones, flowered robes, (all white). [46]

Of the lay costume I can speak with more certainty, as there are several good examples of it, both male and female. The main portion of the male dress is the dhoti, or sheet passed round the waist and then gathered in front, and the gathers passed between the legs, and tucked in behind. This simple arrangement forms a very efficient protection to the loins, and according to the breadth of the sheet it covers the mid thigh, or the knees, or reaches down to the ankles. In the Bharhut Sculptures the dhoti uniformly reaches below the knee, and sometimes down to the mid leg. As there is no appearance of any ornamentation, either of flowers or stripes, it is most probable that then, as now, the dhoti was a plain sheet of cotton cloth. That it was of cotton we learn from the classical writers who drew their information from the companions of Alexander, Thus Arrian says, " The Indians wear cotton garments, the substance whereof they are made " growing upon trees. . . . They wear shirts of the same, which reach down to the " middle of their legs, and veils which cover their head, and a great part of their " shoulders." Here the word rendered shirt by the translator is clearly intended for the well-known Indian dhoti, and the veil must be the equally well-known Chaddar, or sheet of cotton cloth, which the Hindus wrap round their bodies, and also round their heads when they have no separate head-dress. Similarly Q. Curtius states that " the land is prolific of cotton, of which most of their garments are made," and he afterwards adds that " they clothe their bodies down to the feet in cotton cloth (carbaso)." To these extracts I may add the testimony of Strabo, who states that " the Indians wear white garments, white linen, and muslin." But though the cotton dress was white, it was not always plain, as Strabo mentions in another place that " they wear dresses worked with gold and precious stones, and flowered (or variegated) robes." These flowered robes must have been the figured muslins for which India has always been famous.

Above the waist the body is usually represented as quite naked, excepting only a light scarf or sheet, which is generally thrown over the shoulders, with the ends hanging down outside the thighs. In some cases it appears to be passed round the body, and the end thrown over the left shoulder,

The head-dress is by far the most remarkable part of the costume, as it is both lofty and richly ornamented. I have already quoted the description of Prince Siddhartha's hair as braided and plaited, and gathered into a knot on the right side of the head. This description seems to apply almost exactly to the head-dresses in the Bharhut sculptures. But judging from some difierences of detail in various parts, and remembering how the Burmese laymen still wear their hair interwoven with bands and rolls of muslin, I think that of the two terms braided and plaited, one must refer to the hair only, and the other to some bands of cloth intertwisted with the hair. The most complete specimen of the male head-dresses is that of the royal busts on two of the bosses of the rails. The head is about the size of life, and tlie details are all well preserved. In this sculpture, and in the companion medallion of a queen, I observe the bow of a diadem or ribbon, which I take to be a sure sign of royalty. A head-dress of a similar kind is worn by all the Naga Rajas, and in the case of the larger figure of the Naga king Chakavaka I think that I can distinguish the plaited hair from the bands of interwreathed cloth. The two bands which cross exactly above the middle of the forehead appear to be cloth, while all the rest is hair, excepting perhaps a portion of the great knot on the top. Similar cross bands or rolls of cloth may be seen in the head-dresses of the soldiers and standard bearer in Plate XXXII. figs 2, 3, 4, and 5. This interwreathing of muslin with the hair is also described by Q. Curtius, who says that " they wind rolls of muslin round their heads." The plaiting of hair, which I have described above from the Lalita Vistara, was likewise noticed by the Greeks, as Strabo records that " all of them plait their hair and bind it with a fillet." These quotations seem to describe very accurately the peculiar style of head-dresses worn by all men of rank in the Bharhut Sculptures ; and as the chief classical authority for such details was Megasthenes, who resided for many years at Palibothra, their close agreement with the sculptured remains of the same age offers a strong testimony to his general veracity. The only exception that I have observed to the use of this rich head-dress is in that of Kupiro Yakhoo, or Kuvera the King of the Yakshas, who wears an embroidered scarf like that of the females as a head covering.

The ornaments worn by the men will be described along with the female ornaments, as several of them are exactly the same.[47]

The Historical Scenes

Besides the Jatakas, there are large number of other curious scenes, several of them are labelled. Amongst them are some of the greatest historical interest, as they refer directly to events, either true or supposed, in the actual career of sakya muni himself. Of these, six are there with names inscribed over them, and seventh is recognized by its subject. These are as follows:-

- Tikutiko Chakamo

- Maya Devi's dream

- The Jetvana Monastry

- Indra Sala-guha

- Visit of Ajatasatru to Buddha

- Visit of Prasenjit to Buddha

- The Sankika Ladder

Bharhut inscriptions

- Main article: Bharhut inscriptions

There are hundreds of inscriptions found at Bharhut. The Buddhist stupa site of bharhut has yielded some 225 inscriptions, of which 141 are donative in nature while the remaining 84 are labels describing the accompanying sculptural representations of Jatakas, avadanas etc. Bharhut pillar inscription (C I I:2.2,11-12) recording the donation of gateway (torana) provides the only epigraphic attestation of dynastic name Sunga.

Recently found Buddhist remains in region near Bharhut and Sanchi

Several minor Stupas and Buddhist statues have been discovered in the region near Sanchi and Bharhut dating up to 12th century CE. They demonstrate that Buddhism was widespread in this region and not just confined to Sanchi and Bharhut, and survived until 12th century, like the Sanchi complex itself, although greatly declining after 9-10th century. These include:

- Banshipur village, Damoh [48]

- Madighat in Rewa district [49]

- Buddha Danda, Singrauli [50]

- Bilahri, Katni [51]

- Kuwarpur, Sagar Dist/Bansa Damoh Dist[52]

- Damoh Museum Buddha

- Deur Kothar, Rewa

- Devgarh, Lalitpur [53]

- Khajuraho (Museum)[54]

- Mahoba, 11-12th cent. sculptures[55]

भरहुत

विजयेन्द्र कुमार माथुर[56] ने लेख किया है....भरहुत, सतना जिला,(AS, p.666): मध्य प्रदेश के बुन्देलखण्ड के भूतपूर्व नागोद रियासत में स्थित एक ऐतिहासिक स्थान है। भरहुत द्वितीय- प्रथम शताब्दी ईसा पूर्व में निर्मित बौद्ध स्तूप तथा तोरणों के लिए साँची के समान ही प्रसिद्ध है। स्तूप के पूर्व में स्थित तोरण के स्तंभ पर उत्कीर्ण लेख से ज्ञात होता है कि इसका निर्माण 'बाछीपुत धनभूति' ने करवाया था जो गोतीपुत अगरजु का पुत्र और राजा गागीपुत विसदेव का प्रपौत्र था. इस अभिलेख की लिपि से यह विदित होता है कि यह स्तूप शुंगकालीन (प्रथम-द्वितीय शती पूर्व) है और अब इसके केवल अवशेष ही विद्यमान हैं। यह 68 फुट व्यास का बना था। इसके चारों ओर सात फुट ऊँची परिवेष्टनी (चहार दीवारी) का निर्माण किया गया था, जिसमें चार तोरण-द्वार थे। परिवेष्टनी तथा तोरण-द्वारों पर यक्ष-यक्षिणी तथा अन्यान्य अर्द्ध देवी-देवताओं की मूर्तियाँ तथा जातक कथाएँ तक्षित हैं। जातक कथाएँ इतने विस्तार से अंकित हैं कि उनके वर्ण्य-विषय को समझने में कोई कठिनाई नहीं होती। भरहुत और साँची के तोरणों की मूर्तिकारी तथा कला में बहुत साम्यता है। इसका कारण इनका निर्माण काल और विषयों का एक होना है। इसके तोरणों के केवल कुछ ही कलापट्ट कलकता के संग्रहालय में सुरक्षित हैं किन्तु ये भरहुत की कला के सरल सौंदर्य के परिचय के लिए पर्याप्त हैं.

भरहुत भारत के मध्य प्रदेश राज्य में सतना जिले में स्थित एक गाँव है जो अपने प्राचीन बौद्ध स्तूप, कलाकृतियों एवं अन्य पुरातात्विक वस्तुओं के लिए प्रसिद्ध है। यहाँ एक बौद्ध स्तूप के भग्नावशेष प्राप्त हुए हैं जिसका निर्माण सम्राट अशोक या पुष्यमित्र शुंग के काल में हुआ था। अलेक्जैंडर कनिंघम ने सर्वप्रथम 1873 ई. में इस स्थल का पता लगाया था। यहाँ से प्राप्त पुरातात्विक महत्व की कुछ वस्तुओं को कोलकाता के भारतीय संग्रहालय में तथा कुछ अन्य को प्रयागराज के संग्रहालय में रखा गया है।

भरहुत के लाल पहाड़ के ऊपरी चोटी से बलालदेव का 14वीं शदी का प्रारंभिक देवनागरी में लेख मिला है जिससे यह सिद्ध होता है कि इसका महत्त्व इस समय तक था।

भरहुत का स्तूप अपने समय के समाज का दर्पण कहा जा सकता है। वर्तमान में भरहुत उजड़ चुका है।

Gallery

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Bharhut Yavana

References

- ↑ John Marshall, "An Historical and Artistic Description of Sanchi", from A Guide to Sanchi, citing p. 11. Calcutta: Superintendent, Government Printing (1918). Pp. 7-29 on line, Project South Asia.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Mohan Lal varma "Mukut":"Bharhut ki Bolati Shilayen" , Bharhut Stoopa Gatha (Hindi), Ed. Ramnarayan Singh Rana, Satna, 2007, p. 135-136

- ↑ Dr Naval Viyogi: Nagas the Ancient Rulers of India, 2002, p.332

- ↑ Prof. Suddyumn Acharya, Bharhut Stoopa Gatha (Hindi), Ed. Ramnarayan Singh Rana, Satna, 2007, p. 41

- ↑ M.L. Chadhar, Bharhut Stoopa Gatha (Hindi), Ed. Ramnarayan Singh Rana, Satna, 2007, p. 65

- ↑ Dr Naval Viyogi: Nagas the Ancient Rulers of India, 2002, p.332

- ↑ Mahendra Singh Arya et al.: Ādhunik Jat Itihas, Agra 1998, p. 272

- ↑ Jats the Ancient Rulers (A clan study), Bhim Singh Dahiya, p. 333

- ↑ Rose:'Tribes and Castes', Vol. I, p. 84

- ↑ T.W. Rhys Davids, The Buddhist India, 1971, p. 209

- ↑ T.W. Rhys Davids, The Buddhist India, 1971, p. 91

- ↑ Dr C.D. Naik, Bharhut Stoopa Gatha (Hindi), Ed. Ramnarayan Singh Rana, Satna, 2007, p. 25

- ↑ Abha Singh, Bharhut Stoopa Gatha (Hindi), Ed. Ramnarayan Singh Rana, Satna, 2007, p. 119

- ↑ Dr Bhagwandas Safadia, Bharhut Stoopa Gatha (Hindi), Ed. Ramnarayan Singh Rana, Satna, 2007, p. 89

- ↑ Dr Bhagwandas Safadia, Bharhut Stoopa Gatha (Hindi), Ed. Ramnarayan Singh Rana, Satna, 2007, p. 88

- ↑ Dr Hemlata Acharya, Bharhut Stoopa Gatha (Hindi), Ed. Ramnarayan Singh Rana, Satna, 2007, p. 84

- ↑ K D Bajpai, Indian Numismatic studies, p. 16

- ↑ K D Bajpai, Indian Numismatic studies, Ch 5, Pl I,4

- ↑ [http://www.archive.org/stream/cu31924016181111/cu31924016181111_djvu.txt The stūpa of Bharhut: a Buddhist monument ornamented with numerous sculptures,p.3

- ↑ [http://www.archive.org/stream/cu31924016181111/cu31924016181111_djvu.txt The stūpa of Bharhut: a Buddhist monument ornamented with numerous sculptures,p.4

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ Neeraj Jain, Bharhut Stoopa Gatha (Hindi), Ed. Ramnarayan Singh Rana, Satna, 2007, p. 51-52

- ↑ Neeraj Jain, Bharhut Stoopa Gatha (Hindi), Ed. Ramnarayan Singh Rana, Satna, 2007, p. 52-53

- ↑ Alexander Cunningham, The Stupa of Bharhut : A Buddhist Monument Ornamented with Numerous Sculptures Illustrative of Buddhist Legend and History in the Third Century B.C. Reprint. First published in 1879, London. 1998

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britanica

- ↑ Sarvastivada pg 38-39

- ↑ (Shramanas) Ashokavadana, 133, trans. John Strong.

- ↑ Akira Hirakawa, Paul Groner, "A History of Indian Buddhism: From Sakyamuni to Early Mahayana", Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1996, ISBN 8120809556 pg 223

- ↑ Ashok Kumar Anand, "Buddhism in India", 1996, Gyan Books, ISBN 8121205069 pg 91-93

- ↑ Ramsail Garg, Bharhut Stoopa Gatha (Hindi), Ed. Ramnarayan Singh Rana, Satna, 2007, p. 107

- ↑ Neeraj Jain, Bharhut Stoopa Gatha (Hindi), Ed. Ramnarayan Singh Rana, Satna, 2007, pp. 54-55

- ↑ Bharhut Stoopa Gatha (Hindi), Ed. Ramnarayan Singh Rana, Satna, 2007, p.17

- ↑ Haunting the Buddha By Robert DeCaroli, p.73

- ↑ Haunting the Buddha, p.74

- ↑ Mahendra Singh Arya et al.: Ādhunik Jat Itihas, Agra 1998, p.258

- ↑ Harihar Prasad Tewari, Bharhut Stoopa Gatha (Hindi), Ed. Ramnarayan Singh Rana, Satna, 2007, pp. 130

- ↑ Haunting the Buddha, p.73

- ↑ The Jats - Their Origin, Antiquity & Migrations, 1993, p. 150-151

- ↑ Yoginder Pal Shastri, op. cit., p. 468

- ↑ Amichand Sharma, Jat Varna mimansa, v.s. 1967

- ↑ Harihar Prasad Tewari, Bharhut Stoopa Gatha (Hindi), Ed. Ramnarayan Singh Rana, Satna, 2007, pp. 130

- ↑ Haunting the Buddha, p.74

- ↑ Harihar Prasad Tewari, Bharhut Stoopa Gatha (Hindi), Ed. Ramnarayan Singh Rana, Satna, 2007, pp. 130

- ↑ Haunting the Buddha, p.74

- ↑ Bharhut Stoopa Gatha (Hindi), Ed. Ramnarayan Singh Rana, Satna, 2007, p. 8

- ↑ The stūpa of Bharhut: a Buddhist monument ornamented with numerous sculptures pp31-32

- ↑ Buddhist stupas of Gupta period unearthed, Indian Express, June 17, 1999

- ↑ he Statesman, New Delhi, 17/06/99

- ↑ Madhya Pradesh: Swastika-shaped 6th century Stupas found, TOI April 1, 2019

- ↑ Buddha Stolen from Bilhari in Central India, November 30, 2012

- ↑ Y.K. Malaiya, “Research Notes,” Anekanta, Vol. 24, No. 5, November 1971, pp. 213-214

- ↑ Ancient Buddha Vihar, Devgarh

- ↑ An inscribed Buddha image at Khajuraho, Devangana Desai, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Mumbai, Volume 79, p. 63

- ↑ Six Sculptures from Mahoba. BY. K. N. DIKSHIT, New Delhi, 1921

- ↑ Aitihasik Sthanavali by Vijayendra Kumar Mathur, p.666

Further reading

- Alexander Cunningham, The Stupas of Bharhut, 1876

- Benimadhav Barua, BARHUT (PART 1,2,3), 1926

- S C Kala: Bharhut Vedika

- T.W. Rhys Davids, The Buddhist India, 1971

- Bharhut Stoopa Gatha (Hindi), Ed. Ramnarayan Singh Rana, Satna, 2007

External links

- Full text of The stūpa of Bharhut: a Buddhist monument ornamented with numerous sculptures by Alexander Cunningham 1879

- Full text of "CORPUS INSCRIPTIONS INDICARUM VOL II PART II"

- Haunting the Buddha:Indian popular religions and the formation of Buddhism, By Robert DeCaroli, Edition: illustrated, revised Published by Oxford University Press US, 2004, ISBN 0195168380, 9780195168389

Back to Jats in Buddhism

Back to Jat Villages