Chhota Nagpur

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R), Jaipur |

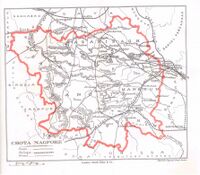

Chhota Nagpur (छोटा नागपुर) is the plateau region which mainly covers the state of Jharkhand and it also also stretches in Chhattisgarh, Bihar and Orissa. Chhotta Nagpur Plateau includes Hazaribagh, Ranchi, Palamau, Singhbhum and Manbhum (present Purulia in West Bengal) districts.

Variants

- Chhota Nagpur (छोटा नागपुर) (AS, p.349)

- Chutia Nagpur

- Chota Nagpur (छोटा नागपुर)

- Chhota-Nagpur (छोटा नागपुर)

- Chhotanagpur (छोटा नागपुर)

- Chhota Nagpur Plateau (छोटा नागपुर पठार)

- Kokara (कोकरा) (AS, p.229)

- Kokrah (कोकरा)

Etymology

The name Nagpur is probably taken from Nagavanshis, who ruled in this part of the country in ancient times. Chota is a corruption of the word Chutia, a village in the outskirts of Ranchi, which has the remains of an old fort belonging to the Nagavanshis.[1] Chutia Naga or Chhota Naga was the name of Nagavanshi King who defended the territory from Mughals and gave name to this region. [2]

Jat Gotras Namesake

Given below is partial list of the peoples or places in Chhota Nagpur of Jharkhand, which have phonetic similarity with Jat clans or Jat Places. In list below those on the left are Jat clans (or Jat Places) and on right are people or place names in Chhota Nagpur Districts. Such a similarity is probably due to the fact that Nagavanshi Jats had been rulers of this area in antiquity as is proved by Inscriptions found in this region and mentioned in Jat History Dalip Singh Ahlawat[3].

History

Dr Naval Viyogi[4] writes... Since the Naga rulers of South India made their colonies in Indonesia and Burma, who reached there by sea as early as 137 AD and used power of their navy to launch incursion as far as South Indo-China or Champa.[5] They carried aforesaid tradition along with them in that region particularly Megalithic tradition went from South India (see map no. II). Under these circumstances tradition of coming of some tribes from the east has no meaning.

However variation in physical type or tradition in individual tribe may be due to some particular reasons in historical age which should be investigated and found out for the satisfaction of all. But evidences of their movement from west are more realiable and based on historical fact and well proved.

The ex-Raja of Chutia or Chhota Nagpur derives their origin from Naga Pundarika. How it happened is most interesting: Pundarika [6],as the story says, once assumed the form of a Brahman and repaired to the house of a certain Guru at Banaras to acquaint himself with the sacred scriptures. The learned instructor was so pleased with his pupil that he gave him to wife his only daughter, the beautiful Parvati. Unfortunately the Naga even in his human form could not rid himself of his double tongue and his foul breath. He begged his wife not to question him about the secret of these unpleasant peculiarities, but once while they were making a pilgrimage of Puri, she insisted on knowing the truth. He had to gratify her curiosity, but having done so, he plunged into a pool and vanished from her sight. In the midst of her grief and remorse, she gave birth to a child. When the child grew up he became king of Chhota Nagpur. The royal family is progeny of the same Naga King.[7]

Famous ancient Buddhist university of Nalanda also had relation with the Nagas. J. Ph Vogel[8], to show above relations, produces archaeological evidences-"A very fine specimen of a seated Naga (See title page) was found on the site of Nalanda in the course of excavations carried out in the cold season of 1920.This Naga holding a rosary in "his right hand and a vase in his left hand is shown sitting in easy posture on the coils of a snake, whose windings are also visible on both sides of the figure,whilst a grand hood of seven cobra-heads forms a canopy over-shadowing him. This image has been tentatively indentified with the Buddhist saint Nagarjuna, master of the Mahayana. The sculpture, how-ever:-presents a type of Naga images peculiar to the mediaeval art of India. (A. S. R. for 1912-13 Part I PI IX 6), although it would be difficult to point out another specimen of equal artistic merit. In this connection, it is interesting to note that according to the Chinese pilgrims Nalanda was named after a Naga (Hieuntsang, si-yu-ki. (Beal) Vol ii P-167). Other instances may be quoted of Buddhist sanctuaries such as Sarnath and Sankisa, which are at the same time dedicated to Serpent worship.

According to Dr Naval Viyogi, It seems from the evidence of Puri Kushan coins that some branch Tanka of Taka royal family owing to attack of Kushanas up to Magadha, reached Mayurbhanj, Singhbhumi, Ganjam and Balasore and established colonies there, where remains of their offshoot, the royal family of Dhavaldev is still existing at Dalbhumigarh near Kharagpur. [9]

In ancient times the area was covered with inaccessible forests inhabited by tribes who remained independent. The entire territory of Chhotanagpur, now known as Jharkhand (meaning forest territory) was presumably beyond the pale of outside influence in ancient India. Throughout the Turko-Afghan period (up to 1526), the area remained virtually free from external influence. It was only with the accession of Akbar to the throne of Delhi in 1557 that Muslim influence penetrated Jharkhand, then known to the Mughals as Kokrah. In 1585, Akbar sent a force under the command of Shahbaj Khan to reduce the Raja of Chotanagpur to the position of a tributary. After the death of Akbar in 1605, the area presumably regained its independence. This necessitated an expedition in 1616 by Ibrahim Khan Fateh Jang, the Governor of Bihar and brother of Queen Noorjehan. Ibrahim Khan defeated and captured Durjan Sal, the 46th Raja of Chotanagpur. He was imprisoned for 12 years but was later released and reinstated on the throne after he had shown his ability in distinguishing a real diamond from a fake one.[10]

In 1632, Chotanagpur was given as Jagir (endowment) to the Governor at Patna for an annual payment of Rs.136,000. This was raised to Rs.161,000 in 1636. During the reign of Muhammad Shah (1719–1748), Sarballand Khan, the Governor of then Bihar, marched against the Raja of Chotanagpur and obtained his submission. Another expedition was led by Fakhruddoula, the Governor of Bihar in 1731. He came to terms with the Raja of Chotanagpur. In 1735 Alivardi Khan had some difficulty in enforcing the payment of the annual tribute of Rs.12,000 from the Raja of Ramgarh, as agreed to by the latter according to the terms settled with Fakhruddoula.

This situation continued until the occupation of the country by the British. During the Muslim period, the main estates in the district were Ramgarh, Kunda, Chai and Kharagdiha. Subsequent to the Kol uprising in 1831 that, however, did not seriously affect Hazaribagh, the administrative structure of the territory was changed. The parganas of Ramgarh, Kharagdiha, Kendi and Kunda became parts of the South-West Frontier Agency and were formed into a division named Hazaribagh as the administrative headquarters. In 1854 the designation of South-West Frontier Agency was changed to Chota Nagpur Division, composed of five districts - Hazaribagh, Ranchi, Palamau, Manbhum, and Singhbhum. The division was administered as a Non-regulation province under a Commissioner reporting to the Lieutenant Governor of Bengal.[11] In 1855-56 there was the great uprising of the Santhals against the British but was brutally suppressed. During British rule, one had to go by train to Giridih and then travel in a vehicle called push-push to Hazaribagh. It was pushed and pulled by human force over hilly tracts. It was an exciting journey across rivers and through dense forests infested with bandits and wild animals. Rabindranath Tagore travelled in a push-push along the route in 1885. He recorded the experience in an essay, "Chotanagpur families". When the Grand Chord railway line was opened in 1906, Hazaribagh Road railway station became the link with the town. For many years, Lal Motor Company operated the rail-cum-bus service between Hazaribagh town and Hazaribagh Road railway station.

In 1912, a new province of Bihar and Orissa was split from Bengal Province. In 1936, the province was split into separate provinces of Bihar and Orissa, with the Chota Nagpur Division being a part of Bihar. Bihar's boundaries remained mostly unchanged after Indian Independence in 1947. Giridih district was created in 1972 by carving some parts of Hazaribagh district. After the 1991 census, the district of Hazaribagh was divided into three separate districts, Hazaribagh, Chatra and Koderma.[12] The two sub-divisions Chatra and Koderma were upgraded to the status of independent districts.

In 2000, Jharkhand was separated from Bihar to become India's 28th state.

In 2007, Ramgarh was separated and made into the 24th district of Jharkhand.

Jat History

Dilip Singh Ahlawat [13] mentions that The Naga Jats ruled over Kantipur, Mathura, Padmavati, Kausambi, Nagpur, Champavati, (Bahgalpur) and in the central India, in western Malwa, Nagaur (Jodhpur- Rajasthan). In addition they ruled the ancient land of Shergarh, (Kotah Rajasthan), Madhya Pradesh (Central India), Chutiya Nagpur, Khairagarh, Chakra Kotiya and Kawardha. The great scholar, Jat Emperor, Bhoja Parmar, mother Shashiprabha was a maiden of a Naga Clan.

Jat clans associated with Chhota Nagpur

- Chusia (चुसिया) Chusiya (चुसिया) is gotra of Jats started after people who moved out from place called Chutia Nagpur or Chhota Nagpur after Nagavanshi Jat King named Chhota Naga. [14]

- Kokra (कोकड़ा) or Kokra (कोकरा) is a gotra of Jats.[15] Kokra (कोकरा) is a variant of Khokar. [16]Bustam Raja, surnamed Kokra, was governor of the Punjab and had his capital at Kokrana[17], present districts of Sargodha and Jhang in Pakistan.

- Agharia (अघरिया) Aghariya (अघरिया) Agaria (अगरिया) are Jat Kshatriyas found in Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Orissa and Chhota Nagpur. They have originated from Agra region and hence known as Agaria which changed to Agharia due to linguistic variations. This link suggests movement of people from Agra/Mathura area to Chhota Nagpur region.

- More Jat clans : See List of Places in Jharkhand Based on Jat Gotras and List of Places in Orissa Based on Jat Gotras

Why Tak Jats moved to Eastern Coast ?

Puri Kushan (पुरी कुषाण), properly called Imitation Kushan, are copper coins discovered in the littoral districts of Ganjam, Puri, Cuttack, Bhadrakand Balasore as well as hill districts in of Mayurbhanj and Keonjhar in Orissa; Ranchi and Singhbhum in Bihar and a few in Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal.[18]

B S Dahiya[19] writes: Tanks or Taks are mentioned by Col. Tod as one of the Thirty –six royal houses of Indian Kshatriyas, but he said about them that they have disappeared from history owing to their conversion to Islam in the Thirteenth Century. But this is not true because they have not disappeared completely as yet; it is true a large number of Tanks are now followers of Islam but there still exist many Tanks among the Hindu Jats also. [20]

A Tak kingdom is mentioned by Hiuen-Tsang (631-643 A.D.). It is mentioned by him as situated towards east of Gandhara. Hiuen-Tasng gives its name as Tekka, and the History of Sindh, Chach-Nama, mentions it as Tak. Its capital was Shekilo (Sakala, modern Sialkot) and formerly King Mihiragula was ruling from this place. In seventh century A.D. its people were not preeminently Buddhists, but worshiped the sun, too. Abhidhana Chintamani says that Takka is the name of Vahika country (Punjab). For what follows, we are indebted to Chandrashekhar Gupta for his article on Indian coins. [21] The Tanks must have come to India, Prior to fourth century A.D. i.e. with the Kushana. And with the Kushanas, they must have spread up to Bengal and Orissa, like the Manns and Kangs who spread into southern Maharashtra and the Deccan. In Orissa, the Tanks, had their rule in Orissa proper, Mayurbhanj, Singbhoom, Ganjam, and Balasore Districts. They are called by historians as “ Puri Kushans” or Kushanas of Puri (Orissa). Their coins have been found at Bhanjakia and Balasore (Chhota Nagpur) and these coins have the legend Tanka written in Brahmi script of the fourth century A.D. Allan suggested the reading Tanka as the name of a tribe “ [22] and others generally accepted the reading Tanka as correct. [23] Allan placed them in the third or early fourth century A.D., while V.A. Smith placed them in the fourth or fifth century A.D. ; R.D. Bannerji called them “ Puri Kushanas” [24]

Dr Naval Viyogi [25] tells that it is not improper to assume that probably these people migrated from the North-West Region of India to the Eastern Coastal area for some unknown reasons. Probably this was due to some political pressure or economic causes. In the vast region comprising - Orissa, Mayurbhanj, Singhbhumi, Ganjam and Balasore districts, they established their colonies. This is supported by the findings of the so called 'Puri Kushan' copper coins from this area.

Dr Naval Viyogi [26] writes that it seems from the evidence of Puri Kushan coins that some branch Tanka of Taka royal family owing to attack of Kushanas up to Magadha, reached Mayurbhanj, Singhbhumi, Ganjam and Balasore and established colonies there, where remains of their offshoot, the royal family of Dhavaldev is still existing at Dalbhumigarh near Kharagpur.

As for the proof that they were Jats, we invite attention to the fact that they still exist as such. Their association with the Kushanas (Kasvan Jats) further supports it. Their central Asian origin is proved by the fact that Niya Khrosthi documents from Central Asia refer to coin denomination as Tangumule. [27] Here the word Tanga is the same as Tanka, and Muli meant “Price” in Central Asia. [28]

Chhotta Nagpur Plateau

Chhotta Nagpur Plateau is one of the primary topographical division of Chhattisgarh. In the north of this plateau lies the Indo Gangetic plain and in its south river Mahanadi has formed its riverine basin. The topography of Chhota Nagpur Plateau is undulating and it is dotted with small hillocks and mounds.

The Chhota Nagpur Plateau can be divided into three parts. The plateau region occupies an area of about 65,509 sq km. The smaller plateau regions of Kodarma, Hazaribagh and Ranchi form parts of Chhota Nagpur Plateau region. Of these three plateaus, the Ranchi plateau is the largest one. The elevation of the plateau land in this part is about 700 meter. Chhottanagpur Plateau is formed of ancient Precambrian rocks.

Chhota Nagpur Plateau is one of the oldest geographical division of India. It is associated with the ancient civilizations of India. This plateau region is also associated with the glorious history of India. The plateau region of India is rich in mineral deposits. There are some tourists sites located near Chhota Nagpur plateau region.

कोकरा

विजयेन्द्र कुमार माथुर[29] ने लेख किया है ...कोकरा (AS, p.229) - कोकरा मुग़ल काल में छोटा नागपुर का नाम था। इसका नामोल्लेख अबुल-फ़ज़ल तथा 'तुजुक-ए-जहाँगीरी' में हुआ है।[30]

छोटा नागपुर

छोटा नागपुर (AS, p.349)- इस प्रदेश का नाम, किवदंती के अनुसार, छोटानाग नामक नागवंशी राजकुमार-सेनापति के नाम पर पड़ा है. छोटानाग ने, जो तत्कालीन नागराजा का छोटा भाई था, मुगलों की सेना को हराकर अपने राज्य की रक्षा की थी. सरहूल की लोककथा छोटानाग से संबंधित है. इस नाम की आदिवासी लड़की ने अपने प्राण देकर छोटानाग की जान बचाई थी. सर जॉन फाउल्टन का मत है कि छोटा या छुटिया रांची के निकट एक गांव का नाम है जहां आज भी नागवंशी सरदारों के दुर्ग के खंडहर हैं. इनके इलाके का नाम नागपुर था और छुटिया या छोटा इसका मुख्य स्थान था. इसीलिए इस क्षेत्र को छोटा नागपुर कहा जाने लगा. (देखें: सर जॉन फाउल्टन - बिहार दि हार्ट ऑफ इंडिया, पृ. 127) छोटा नागपुर के पठार में हजारीबाग, रांची, पालामऊ, मानभूम और सिंहभूम के जिले सम्मिलित हैं. [31]

छोटा नागपुर परिचय

छोटा नागपुर भारत में स्थित एक पठार है जिसका ज़्यादातर हिस्सा झारखंड और कुछ हिस्से उड़ीसा, बिहार और छत्तीसगढ़ में फैले हुये हैं। यह पठार पूर्व कैंब्रियन युगीन (5,4000,000, वर्ष से भी अधिक पुरानी) चट्टानों से बना है। रांची, हज़ारीबाग़ और कोडरमा के पठारों का संयुक्त नाम ही छोटा नागपुर है। इसकी मुख्य विशेषताओं में से एक 'पाट भूमि' है। इसे 'भारत का रूर' भी कहा जाता है, क्योंकि यहाँ संसाधनों की प्रचुरता है।

क्षेत्रफल: छोटा नागपुर का क्षेत्रफल 65,509 वर्ग किमी इसका बड़ा हिस्सा रांची का पठार है, जिसकी औसत ऊंचाई 700 मीटर है। छोटा नागपुर का समूचा पठार उत्तर में गंगा और सोन के बेसिन और दक्षिण में महानदी के बेसिन के बीच स्थित है; इसके मध्य भाग में पश्चिम से पूर्व दिशा में कोयला क्षेत्र वाली दामोदर घाटी गुजरती है।

उत्पादन: सदियों से भारी पैमाने पर होने वाली खेती ने पठार की अधिकांश प्राकृतिक वनस्पति को नष्ट कर दिया है, इसके बावजूद अब भी कुछ महत्त्वपूर्ण वन बचे हुए है। टसर रेशम और लाख जैसे वन उत्पाद आर्थिक रूप से महत्त्वपूर्ण हैं। भारत में खनिज संसाधनों का सबसे महत्त्वपूर्ण संकेंद्रण छोटा नागपुर में है। दामोदर घाटी में कोयले के विशाल भंडार हैं और हज़ारीबाग़ ज़िला विश्व में अभ्रक के प्रमुख स्त्रोतों में से एक है। अन्य खनिज हैं-तांबा, चूना-पत्थर, बॉक्साईट, लौह अयस्क, एस्बेस्टॉस और ऐपाटाइट (फ़ॉस्फ़ेट उर्वरक के उत्पादन में उपयोगी) बोकारो में एक विशाल तापविधुत संयंत्र और इस्पात कारख़ाना है। इस पठार से गुजरने वाले रेलमार्ग इसे दक्षिण-पूर्व में कोलकाता (भूरपूर्व कलकत्ता) और उत्तर में पटना से जोड़ते हैं और दक्षिण तथा पश्चिम के अन्य नगरों से भी संपर्क उपलब्ध कराते है।

संदर्भ: भारतकोश-छोटा नागपुर

Notable persons

External links

References

- ↑ Sir John Houlton, 'Bihar, the Heart of India', pp. 127-128, Orient Longmans, 1949.

- ↑ Aitihasik Sthanavali by Vijayendra Kumar Mathur, p.349

- ↑ Jat History Dalip Singh Ahlawat/Chapter III, p.242

- ↑ Dr Naval Viyogi: Nagas – The Ancient Rulers of India, p.26

- ↑ Mahajan V.D. "Prachin Bharat Ka Itihas",p.779

- ↑ Vogel J PH, p.35

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ Vogel J PH,p.43

- ↑ Dr Naval Viyogi: Nagas – The Ancient Rulers of India, p.158

- ↑ https://hazaribag.nic.in/history/

- ↑ Chota Nagpur Division" in The Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1909, Clarendon Press, Oxford. Vol. 10, Page 328.

- ↑ "HISTORY/District Court in India | Official Website of District Court of India". districts.ecourts.gov.in.

- ↑ Jat History Dalip Singh Ahlawat/Chapter III, p.242

- ↑ Dr Mahendra Singh Arya etc,: Ādhunik Jat Itihas, Agra 1998 p.242

- ↑ डॉ पेमाराम:राजस्थान के जाटों का इतिहास, 2010, पृ.297

- ↑ A glossary of the Tribes and Castes of the Punjab and North-West Frontier Province By H.A. Rose Vol II/K, pp.540-541

- ↑ A glossary of the Tribes and Castes of the Punjab and North-West Frontier Province By H.A. Rose Vol II/K, pp.540-541

- ↑ 'Newly Found Imitation Kushan Coin Hoard From Dolashai, Bhadrak Orissa' by Ajay Kumar Nayak

- ↑ Jats the Ancient Rulers (A clan study)/Jat Clan in India,p. 273-274

- ↑ Bhim Singh Dahiya, Jats the Ancient Rulers ( A clan study), p. 274

- ↑ Vishveshvaranand Indological Journal (Hoshiarpur, Pb.) Vol, XVI, pt. I. p.92 ff

- ↑ Ancient India, Plate XII, fig. 3

- ↑ Journal of Numismatic Society of India, 12, 1950 p.72

- ↑ Bhim Singh Dahiya, Jats the Ancient Rulers ( A clan study), p. 274

- ↑ Dr Naval Viyogi: Nagas – The Ancient Rulers of India, p.157

- ↑ Dr Naval Viyogi: Nagas – The Ancient Rulers of India, p.158

- ↑ ibid., 16-1954 p. 220 f.n. 4

- ↑ Bhim Singh Dahiya, Jats the Ancient Rulers ( A clan study), p. 274

- ↑ Aitihasik Sthanavali by Vijayendra Kumar Mathur, p.229

- ↑ Aitihasik Sthanavali by Vijayendra Kumar Mathur, p.229

- ↑ Aitihasik Sthanavali by Vijayendra Kumar Mathur, p.349

Back to Mountains