Indus Valley Civilization: Difference between revisions

| Line 179: | Line 179: | ||

The Indus Valley people were very resolute and flexible and continued to evolve even in the face of declining monsoon. The people shifted their crop patterns from large-grained cereals like wheat and barley during the early part of intensified monsoon to drought-resistant species like rice in the latter part. As the yield diminished, the organised large storage system of the Mature Harappan period gave way to more individual household-based crop processing and storage systems that acted as a catalyst for the de-urbanisation of the civilization rather than an abrupt collapse, they say. | The Indus Valley people were very resolute and flexible and continued to evolve even in the face of declining monsoon. The people shifted their crop patterns from large-grained cereals like wheat and barley during the early part of intensified monsoon to drought-resistant species like rice in the latter part. As the yield diminished, the organised large storage system of the Mature Harappan period gave way to more individual household-based crop processing and storage systems that acted as a catalyst for the de-urbanisation of the civilization rather than an abrupt collapse, they say. | ||

== 900-year drought wiped out Indus civilisation: IIT-Kharagpur == | |||

Ref - [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/900-year-drought-wiped-out-indus-civilisation-iit-kharagpur/articleshow/63776710.cms Jhimli Mukherjee Pandey, Times of India, Apr 16, 2018] | |||

The Indus Valley civilisation was wiped out 4,350 years ago by a 900-year-long drought, scientists at the Indian Institute of Technology in Kharagpur (IIT-Kgp) have found. Evidence gathered during their study also put to rest the widely accepted theory that the said drought lasted for only about 200 years. | |||

The study will be published in the prestigious Quaternary International Journal by Elsevier this month. | |||

Researchers from the geology and geophysics department have been studying the monsoon’s variability for the past 5,000 years and have found that the rains played truant in the northwest Himalayas for 900 long years, drying up the source of water that fed the rivers along which the civilisation thrived. This eventually drove the otherwise hardy inhabitants towards the east and south, where rain conditions were better. | |||

The IIT-Kgp team mapped a 5,000-year monsoon variability in the Tso Moriri Lake in Leh-Ladakh — which too was fed by the same glacial source — and identified periods that had continuous spells of good monsoon as well as phases when it was weak or nil. | |||

“The study revealed that from 2,350 BC (4,350 years ago) till 1,450 BC, the monsoon had a major weakening effect over the zone where the civilisation flourished. A drought-like situation developed, forcing residents to abandon their settlements in search of greener pastures,” said Anil Kumar Gupta, the lead researcher and a senior faculty of geology at the institute. | |||

Top Comment | |||

Final nail in the myth of Aryan InvasionSachin Kondke | |||

These displaced people gradually migrated towards the Ganga-Yamuna valley towards eastern and central UP; Bihar and Bengal in the east; MP, south of Vindhyachal and south Gujarat in the south, Gupta added. | |||

== The Harappan Civilization and cult of Naga Worship == | == The Harappan Civilization and cult of Naga Worship == | ||

[[Image:Naga Seals from Indus Valley.jpg|thumb|Naga Seals from [[Indus Valley]]]] | [[Image:Naga Seals from Indus Valley.jpg|thumb|Naga Seals from [[Indus Valley]]]] | ||

Revision as of 12:36, 19 April 2018

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Indus Valley Civilization (सिंधु घाटी सभ्यता) was a Bronze Age civilization (3300–1300 BCE; mature period 2600–1900 BCE) extending from what today is northeast Afghanistan to Pakistan and northwest India.

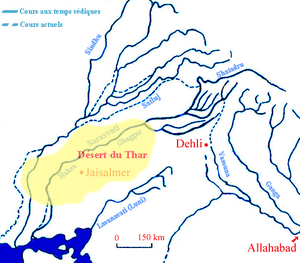

River Basins

It flourished in the basins of the Indus River, one of the major rivers of Asia, and the Ghaggar-Hakra River, which once coursed through northwest India and eastern Pakistan.

Also known as Harappan Civilization

The Indus Valley Civilization is also known as the Harappan Civilization, after Harappa, the first of its sites to be excavated in the 1920s, in what was then the Punjab province of British India, and is now in Pakistan.[1] The discovery of Harappa, and soon afterwards, Mohenjo-Daro, was the culmination of work beginning in 1861 with the founding of the Archaeological Survey of India in the British Raj.[2] Excavation of Harappan sites has been ongoing since 1920, with important breakthroughs occurring as recently as 1999.[3] There were earlier and later cultures, often called Early Harappan and Late Harappan, in the same area of the Harappan Civilization. The Harappan civilization is sometimes called the Mature Harappan culture to distinguish it from these cultures. By 1999, over 1,056 cities and settlements had been found, of which 96 have been excavated,[4] mainly in the general region of the Indus and Ghaggar-Hakra Rivers and their tributaries.

Sites of Indus Valley Civilization

The Indus cities are noted for their urban planning, baked brick houses, elaborate drainage systems, water supply systems, and clusters of large non-residential buildings.[5] Among the settlements were the major urban centres of Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Dholavira, Ganeriwala and Rakhigarhi.[6]

Here is the list of sites in Indus Valley Civilization:

- Alamgirpur (Meerut Tahsil & District, Uttar Pradesh, India) - Eastern most IVC site

- Allahdino (Karachi, Pakistan)

- Amri (Dadu district, Sindh province, Pakistan)

- Babar Kot (Saurashtra, Gujarat, India)

- Banawali (Fatehabad tahsil & district, Haryana, India)

- Balu (Kaithal tahsil and district, Haryana, India)

- Bara Punjab (Rupnagar district Punjab, India)

- Bargaon (Saharanpur District, Uttar Pradesh, India)

- Baror (Sri Ganganagar district, Rajasthan, India)

- Bet Dwarka (Devbhoomi Dwarka district, Gujarat, India)

- Bhagatrav (Bharuch District, Gujarat, India)

- Bhagwanpur Thanesar (Thanesar tahsil, Kurukshetra district, Haryana)

- Bhirrana (Fatehabad district, Haryana, India)

- Budana (ta:Narnaud, Hisar, Haryana)

- Chanhudaro (Nawabshah District, Sindh, Pakistan)

- Dabarkot (Loralai District, Balochistan, Pakistan)

- Daimabad (Ahmadnagar District, Maharashtra, India)

- Desalpar Gunthli (Nakhtrana Taluka, Kutch, District Gujarat, India)

- Dher Majra (Rupnagar district, Indian state of Punjab)

- Dholavira (Khadirbet in Bhachau Taluka of Kutch District, Gujarat, India)

- Gamra (ta:Narnaud, Hisar, Haryana)

- Ganeriwala (Cholistan, Punjab, Pakistan)

- Ganeshwar (Neem Ka Thana tahsil, Sikar district, Rajasthan, India)

- Gianpura (tahsil and district Hisar, Haryana)

- Gola Dhoro (Bagasara, Amreli district, Gujarat, India)

- Gunkali (Jind District in Haryana)

- Haibatpur (Jind tehsil and district of Haryana)

- Harappa (Sahiwal District, Punjab, Pakistan)

- Hisar (inside Firoz Shah Palace, Hisar District, Haryana, India)

- Hulas (Saharanpur District, Uttar Pradesh, India)

- Jognakhera (Tahsil Thanesar, Kurukshetra district, Haryana, India)

- Kagsar (Narnaund tehsil, Hisar, Haryana)

- Kalibangan (Kalibangan of Pillibangan Tehsil, Ditrict Hanumangarh, Rajasthan, India)

- Kanmer (Rapar Taluk, Kutch District, Gujarat, India)

- Kanwari (Hansi Tehsil , Hisar district, Haryana, India)

- Karanpura Hanumangarh (Bhadra tehsil, Hanumangarh, Rajasthan)

- Karanpura (near Bhadra city, Hanumangarh district, Rajasthan, India)

- Kerala-no-dhoro or Padri (Padari, Bhavnagar district of Saurashtra, Gujarat, India)

- Kheri Jalab (Narnaud Tehsil, district Hisar, Haryana)

- Kheri Lochab (Narnaud Tehsil, district Hisar, Haryana)

- Khirasara (Nakhatrana Taluka, Kutch District, Gujarat)

- Kinnar (Narnaund tehsil of district Hisar, Haryana)

- Kot Bala (Lasbela District, Balochistan, Pakistan)

- Kot Diji (Khairpur District, Sindh, Pakistan)

- Kotla Nihang Khan (Rupnagar, Punjab, India)

- Kulli (Balochistan (Gedrosia) in Pakistan)

- Kunal (Fatehabad District, Haryana, India)

- Kuntasi (Maliya taluka, Rajkot District (now Morbi district), Gujarat, India)

- Lakhueen-jo-daro (Sukkur District, Sindh, Pakistan)

- Larkana (Larkana District, Sindh, Pakistan)

- Lohari Ragho (Narnaund tahsil, Hisar, Haryana)

- Loteshwar (Mehsana District, Gujarat, India)

- Lothal (Village of Saragwala, Dholka taluka, Ahmedabad district, Gujarat, India

- Manda Jammu (Jammu District, Jammu & Kashmir, India) - Northern most IVC site

- Malwan (Surat District, Gujarat, India) - Southern most IVC site

- Mandi (Muzaffarnagar district, Uttar Pradesh, India)

- Masudpur ((Hansi Tehsil, Hisar district, Haryana)

- Mehrgarh (Kachi Distric, Balochistan, Pakistan)

- Milkpur (Narnaund tahsil, Hisar district, Haryana)

- Mirchpur (Narnaund tahsil, Hisar district, Haryana)

- Mitathal (Bhiwani District, Haryana, India)

- Mohenjo-daro (Larkana District, Sindh, Pakistan)

- Mundigak (Kandahar Province, Kandahar, Afghanistan)

- Nagwada (Dasada Taluka, Surendranagar District, Gujarat, India)

- Nara (Narnaund tehsil, district Hisar, Haryana)

- Naurangabad Jattan (Charkhi Dadri tahsil, Bhiwani district, Haryana, India)

- Nausharo (Near Dadhar, Kachi District, Balochistan, Pakistan)

- Nindowari (Kalat District of Balochistan, Pakistan)

- Pabumath (Kutch District, Gujarat, India)

- Pali (Tehsil Narnaund , Hisar District,Haryana)

- Panhari (tahsil Hisar and district Hisar, Haryana)

- Pir Shah Jurio (Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan)

- Pirak (Sibi district, Balochistan, Pakistan)

- Rajpura (Narnaund tehsil, district Hisar, Haryana)

- Rakhigarhi (Village Rakhigarhi, Hisar district, Haryana, India)

- Rangpur (Ahmedabad District, Gujarat, India)

- Rehman Dheri (Dera Ismail Khan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan)

- Rojdi (Rajkot District, Gujarat, India)

- Rupnagar (Rupnagar district in Punjab, India)

- Sanauli (Baraut tahsil, Baghpat District, Uttar Pradesh, India)

- Sanghol (Khamanon tahsil, district Fatehgarh Sahib, Punjab, India)

- Sheri Khan Tarakai (Bannu District, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan)

- Shikarpur (Bhachau Taluka, Kutch District, Gujarat, India)

- Shahr-i-Sokhta (Sistan Basin, Helmand River, Arghandab, Kandahar Sarasvati, Afghanistan)

- Sisai (ta:Hansi, Hisar, Haryana)

- Sokhta Koh (Pasni:Cysa in Arrian's treatise Indica, Gwadar District, Makran, Balochistan, Pakistan)

- Shortugai (Takhar Province, Afghanistan)

- Siswal (Adampur tehsil, Hisar district, Haryana, India)

- Sotha (Hisar, Haryana, India)

- Sothi (Baraut, Bagpat district, Uttar Pradesh, India)

- Sulchani (Narnaund tehsil, Hisar district, Haryana)

- Surkotada (Kutch District, Gujarat)

- Sutkagan Dor (Makran, Balochistan, Pakistan) - Western most IVC site

- Tepe Yahya (Kermān Province, Iran)

Indus era 8,000 years old, not 5,500

Ref - Jhimli Mukherjee Pandey,Times of India, Jaipur, May 29, 2016

It may be time to rewrite history textbooks. Scientists from IIT-Kharagpur and Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) have uncovered evidence that the Indus Valley Civilization is at least 8,000 years old, and not 5,500 years old, taking root well before the Egyptian (7000BC to 3000BC) and Mesopotamian (6500BC to 3100BC) civilizations. What's more, the researchers have found evidence of a pre-Harappan civilization that existed for at least 1,000 years before this.

The discovery, published in the prestigious 'Nature' journal on May 25, may force a global rethink on the timelines of the so-called 'cradles of civilization'. The scientists believe they also know why the civilization ended about 3,000 years ago — climate change.

"We have recovered perhaps the oldest pottery from the civilization. We used a technique called 'optically stimulated luminescence' to date pottery shards of the Early Mature Harappan time to nearly 6,000 years ago and the cultural levels of pre-Harappan Hakra phase as far back as 8,000 years," said Anindya Sarkar, head of the department of geology and geophysics at IIT-Kgp.

The team had actually set out to prove that the civilization proliferated to other Indian sites like Bhirrana and Rakhigarrhi in Haryana, apart from the known locations of Harappa and Mohenjo Daro in Pakistan and Lothal, Dholavira and Kalibangan in India. They took their dig to an unexplored site, Bhirrana — and ended up unearthing something much bigger. The excavation also yielded large quantities of animal remains like bones, teeth, horn cores of cow, goat, deer and antelope, which were put through Carbon 14 analysis to decipher antiquity and the climatic conditions in which the civilization flourished, said Arati Deshpande Mukherjee of Deccan College, which helped analyse the finds along with Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad.

The researchers believe that the Indus Valley Civilization spread over a vast expanse of India — stretching to the banks of the now "lost" Saraswati river or the Ghaggar-Hakra river - but this has not been studied enough because what we know so far is based on British excavations. "At the excavation sites, we saw preservation of all cultural levels right from the pre-Indus Valley Civilization phase (9000-8000 BC) through what we have categorised as Early Harappan (8000-7000BC) to the Mature Harappan times," said Sarkar.

While the earlier phases were represented by pastoral and early village farming communities, the mature Harappan settlements were highly urbanised with organised cities, and a much developed material and craft culture. They also had regular trade with Arabia and Mesopotamia. The Late Harappan phase witnessed large-scale de-urbanisation, drop in population, abandonment of established settlements, lack of basic amenities, violence and even the disappearance of the Harappan script, the researchers say.

"We analysed the oxygen isotope composition in the bone and tooth phosphates of these remains to unravel the climate pattern. The oxygen isotope in mammal bones and teeth preserve the signature of ancient meteoric water and in turn the intensity of monsoon rainfall. Our study shows that the pre-Harappan humans started inhabiting this area along the Ghaggar-Hakra rivers in a climate that was favourable for human settlement and agriculture. The monsoon was much stronger between 9000 years and 7000 years from now and probably fed these rivers making them mightier with vast floodplains," explained Deshpande Mukherjee.

Indus Valley evolved even as monsoon declined:

They took their dig to an unexplored site, Bhirrana — and ended up unearthing something much bigger. The excavation also yielded large quantities of animal remains like bones, teeth, horn cores of cow, goat, deer and antelope, which were put through Carbon 14 analysis to decipher antiquity and the climatic conditions in which the civilization flourished, said Arati Deshpande Mukherjee of Deccan College, which helped analyse the finds along with Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad.

The researchers believe that the Indus Valley Civilization spread over a vast expanse of India — stretching to the banks of the now "lost" Saraswati river or the Ghaggar-Hakra river — but this has not been studied enough because what we know so far is based on British excavations. "At the excavation sites, we saw preservation of all cultural levels right from the pre-Indus Valley Civilisation phase (9,000-8,000 years ago) through what we have categorised as Early Harappan (8,000-7,000 years ago) to the Mature Harappan times," said Sarkar.

The late Harappan phase witnessed large-scale de-urbanisation, drop in population, abandonment of established settlements, violence and even the disappearance of the Harappan script, the researchers say. The study revealed that monsoon started weakening 7,000 years ago but, surprisingly, the civilization did not disappear.

The Indus Valley people were very resolute and flexible and continued to evolve even in the face of declining monsoon. The people shifted their crop patterns from large-grained cereals like wheat and barley during the early part of intensified monsoon to drought-resistant species like rice in the latter part. As the yield diminished, the organised large storage system of the Mature Harappan period gave way to more individual household-based crop processing and storage systems that acted as a catalyst for the de-urbanisation of the civilization rather than an abrupt collapse, they say.

900-year drought wiped out Indus civilisation: IIT-Kharagpur

Ref - Jhimli Mukherjee Pandey, Times of India, Apr 16, 2018

The Indus Valley civilisation was wiped out 4,350 years ago by a 900-year-long drought, scientists at the Indian Institute of Technology in Kharagpur (IIT-Kgp) have found. Evidence gathered during their study also put to rest the widely accepted theory that the said drought lasted for only about 200 years.

The study will be published in the prestigious Quaternary International Journal by Elsevier this month.

Researchers from the geology and geophysics department have been studying the monsoon’s variability for the past 5,000 years and have found that the rains played truant in the northwest Himalayas for 900 long years, drying up the source of water that fed the rivers along which the civilisation thrived. This eventually drove the otherwise hardy inhabitants towards the east and south, where rain conditions were better.

The IIT-Kgp team mapped a 5,000-year monsoon variability in the Tso Moriri Lake in Leh-Ladakh — which too was fed by the same glacial source — and identified periods that had continuous spells of good monsoon as well as phases when it was weak or nil.

“The study revealed that from 2,350 BC (4,350 years ago) till 1,450 BC, the monsoon had a major weakening effect over the zone where the civilisation flourished. A drought-like situation developed, forcing residents to abandon their settlements in search of greener pastures,” said Anil Kumar Gupta, the lead researcher and a senior faculty of geology at the institute.

Top Comment

Final nail in the myth of Aryan InvasionSachin Kondke

These displaced people gradually migrated towards the Ganga-Yamuna valley towards eastern and central UP; Bihar and Bengal in the east; MP, south of Vindhyachal and south Gujarat in the south, Gupta added.

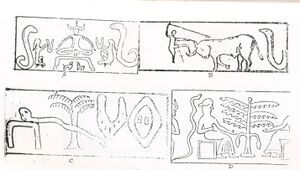

The Harappan Civilization and cult of Naga Worship

Dr Naval Viyogi[7]writes that The Indus Valley Civilization which is the most ancient civilization of India, was spread up in North-West: Harappa, Mohenjodaro , Chanhudaro and Lothal were its most important towns. The founders of Indus valley civilization were Mediterraneans or Dravidians and Australoids, [8] where as, round headed Alpines, appeared, in mature age of this culture. [9] In excavation of these towns, in addition to Burnished Red ware, a very high number of seals and seal impressions have also been found out. Among the seals so found out on one seal, there is a figure of chief deity with buffalo head, on its both sides, are two other man deities and behind each of them is a serpent in standing posture (See Illustration - Seal A). On another seal, there is a serpent, in standing posture, behind the bull, which is fighting with a mighty man (See Illustration - Seal B). [10] On another third seal, there is a serpent resting his head on a Wooden bench or seat, which is protecting a tree deity (See Illustration - Seal C). [11]

The presence of serpents on all the above three seals, establishes that the Naga (serpent) was their (Harappans) protector deity and symbol of authority of rule. We can draw the following conclusion from the above detail:

- The tradition of serpent worship or totemisim was prevalent in Indus Valley Civilization

- The scene depicted on the seal no.-2 (See Illustration - Seal B), shows its relation with the myths of Bobylonia, which proves origin of this tradition on Western Asia.

This fact finding is further corroborated by seal, No.4 (See Illustration - Seal D) This figure is incised on a cylinder seal recovered form Babylonia (Lajards culte de Mithra). This proves the origin of tradition of tree and serpent worship in Babylonia, from where later on it was transferred to Indus Valley. [12]

References

- ↑ Beck, Roger B.; Linda Black, Larry S. Krieger, Phillip C. Naylor, Dahia Ibo Shabaka, (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell.

- ↑ Wright, Rita P. (2010), The Ancient Indus: Urbanism, Economy, and Society, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-57219-4,p.2

- ↑ "'Earliest writing' found". BBC News. 4 May 1999

- ↑ Morrison, Kathleen D. (Ed.); Junker, Laura L. (2002). Forager-traders in South and Southeast Asia : long term histories ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 62. ISBN 9780521016360.

- ↑ Wright, Rita P. (2010), The Ancient Indus: Urbanism, Economy, and Society, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-57219-4,pp.115-125

- ↑ Wright, Rita P. (2010), The Ancient Indus: Urbanism, Economy, and Society, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-57219-4,p.107

- ↑ Dr Naval Viyogi: Nagas – The Ancient Rulers of India, P.227

- ↑ Whealer R.E.M., “A.I.” Vol III Bulletin of Archaeological Survey of India (January,1947); Bose N.K. and others “Human Skeleton from Harappa” ASIC (1963) pp.58-59

- ↑ Sarkar S.S., “Aboriginal Races of India”, pp.143-45

- ↑ Sastri Kedarnath, New lights on the Indus Civilization” Vol I p.35

- ↑ Dr Naval Viyogi: Nagas the Ancient Rulers of India, p.228

- ↑ Dr Naval Viyogi: Nagas the Ancient Rulers of India, p.229