Parihar

| Author:Laxman Burdak, IFS (R) |

Parihar (परिहार)[1]/ Pratihar (प्रतिहार)[2] [3] Parhar (पड़हार) Padhiyar (पढियार) Parhiyar (पढियार) Padiyar (पडियार) Padiyal (पडियाल) is gotra of Jats found in Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat in India and in Pakistan. They are called Padhiyar in Gujarat, Parhiyar in Sindh, Pakistan. Pratihara (प्रतिहार) are Agnivanshi Jats. [4] They are also found in Gujars and Rajputs. Pari clan is found in Afghanistan.[5] James Tod places it in the list of Thirty Six Royal Races.[6]

Origin

The Sanskrit equivalent of Parihar is Pratihar (प्रतिहार). The word "Pratihara" means keeper or protector, and was used by the Gurjara-Pratihara rulers as self-designation. The Pratihara rulers claim descent from the Hindu mythological character Lakshmana, who had performed the duty of a door-keeper (pratihara) for his elder brother Rama.

A 1966 book published by the Directorate of Public Relations Government of Rajasthan mentions that the kings of this dynasty came to be known as the Pratiharas, because they guarded the north-western borders of the Indian subcontinent against foreign invasions.[7]

The Pratiharas spread from Mandor in Rajasthan. One of its branched moved to Bhinmal (Jalor) under leadership of Nagabhatta I (730-756 AD). Since their place of origin was Gurjaratra hence in Jalor they were called Gurjaras on the basis of their place of Origin. When they came to Kanauj they were known as Gurjara-Pratiharas. After the fall of Pratiharas Chalukyas came into power and the worder Gurjar continued to be in use for next three centuries. Slowly word Gurjar was used for the entire territory ruled by Chalukyas. Gurjaratra in Prakrat form was Gujarat. [8]

According to D.R. Bhandarkar[9] Gurjaratra comprised the districts of Didwana and Parbatsar of the princely Jodhpur State, now in Nagaur district in Rajasthan. Gurjaratra can be considered to be a sandhi of Gur + Jarta = Gurjarata = Gurjaratra. Gur means great and Jarta is identified with Jats by many historians. It means 'Great Jats' same as Massagetae of Herodotus.

R.C. Majumdar in the "The Gurjara Pratiharas"[10] mentions verse 18 of Jodhpur Inscription of Bauka dated 837 which tells us that he fixed the perpetual boundary of the provinces of Travani and Valla. Now these two provinces, along with a few others are said to have been included in the territories of Kakkuka, the 14th king of the dynasty. It may be held, therefore, that there was some disturbance in the kingdom. That some danger had befallen it is also implied in the next verse wherein we are told that the protector of Vallamandala gained the confederacy of the Bhattis by overthrowing Devaraja. [11]

Here the, Bhattis seem to be the name of the sab-clan to which the rulers belonged, for in verse 26 of inscription No. I, Padmini the queen of Kakka, is said to be the purifier of the Bhatti clan. Bhati is a Jat clan. Travani (त्रवणी) is the same as Tivari (तिवरी), a Village in Osian tahsil of Jodhpur district in Rajasthan. Jat history tells us that Tawal (तावल) gotra of Jats originated from this place. [12]

Vallamandala ( वल्लमण्डल) is mentioned in V.19 of Jodhpur Inscription of Bauka dated 837 and also in verse-3 of Ghatiyala Inscriptions of Kakkua dated 861 AD. Here Valla is sanskritized form of Ball (बल्ल) or Bal (बल). Thus this represents the 'Bal Division' (बलमण्डल) mentioned in Jat history. We know that Ball (बल्ल) or Bal (बल) or Balhara (बलहारा) are all Jat clans. Balhara needs a special mention here. In Sanskrit, "Bal" means "strength" and "hara" means "the possessor". Balhara means "the possessor of strength". About the origin of Balhara, the early Arab Geographers are unanimous in their spelling of the title "Balhará." The merchant Sulaimán says it is a title and not a proper name. Ibn Khurdádba says that it signifies "King of Kings." Balhara Jats were the rulers in Sindh and Rajasthan from 8th to 10th century. Balharas ruled the area, which can be remembered as 'Bal Division' (बलमण्डल) . [13]

It is a well known fact that the Arabs had established themselves in Sindh at the beginning of the eighth century A.D. and used to send military expeditions into the interior from time to time. The Nausari plates of the Gujarat Chalukya Pulakesiraja, dated in 738 A.D., refers to an expedition of the Arabs in course of which they are said to have defeated the kings of the Saindhavas 1, the Kachchhellas 2, Saurashtra 3, the Chavotakas 4, the Mauryas 5and the Gurjaras 6. It seems very likely that the Arab invasion referred to in the grant was that undertaken by the officers of Junaid, the general of Kalif Hasham (724-743 AD).

It is interesting to nate that 1. Sindhu (सिंधु), 2. Kachela (काचेला), 3. Sorout (सोरोत), 4. Chapotkat (चपोत्कट)/ Chapu (चापू), 5. Maurya (मौर्य) / Mor (मोर), 6. Gurjara (गूर्जर) mentioned above are all in the list of Jat clans. Thakur Deshraj[14] tells us that a group of Jats around Kandahar was known as Gujar.

These facts in view of the Arab raids indicate that a confederacy of existing clans was formed to fight with Arab invaders. This led to the rise of a new ruling dynasty among the Pratiharas.

Jat Gotras Namesake

In Mahabharata period

In Mahabharata epic we find mention of Dwarapala tribe which is synonymous with Pratihara, who are dwelling in the neighbourhood of Ramathas. Thus the search of Ramatha from various Parvas we can find Pratihara Kshatriyas located on the western borders of India in Mahabharata period.

Sabha Parva, Mahabharata/Book II Chapter 29 mentions deeds and triumphs of Nakula where he defeats Dwarapala tribe which is synonymous with Pratihara.

- ". ....and the whole of the country called after the five rivers Panchanada, and the mountains called Amara , and the country called Uttarajyoti and the city of Divyakutta and the tribe called Dwarapala. And the son of Pandu, by sheer force, reduced to subjection the Ramathas, the Harahunas, and various kings of the west..."

- कृत्स्नं पञ्चनदं चैव तदैवापरपर्यटम

- उत्तरज्यॊतिकं चैव तदा वृण्डाटकं पुरम

- द्वारपालं च तरसा वशे चक्रे महाथ्युतिः (Mahabharata, 2.29.10)

- रमठान हारहूणांश च परतीच्याश चैव ये नृपाः

- तान सर्वान स वशे चक्रे शासनाथ एव पाण्डवः (Mahabharata, 2.29.10)

Vana Parva, Mahabharata/Book III Chapter 48 mentions chiefs of many islands and countries on the sea-board as also of frontier states who attended Rajasuya sacrifice of Yudhisthira:

- ...all the kings of the West by hundreds, and all the chiefs of the sea-coast, and the kings of the Pahlavas and the Daradas and the various tribes of the Kiratas and Yavanas and Sakras and the Harahunas and Chinas and Tukharas and the Sindhavas and the Jagudas and the Ramathas and the Mundas and the inhabitants of the kingdom of women and the Tanganas...

- पश्चिमानि च राज्यानि शतशः सागरान्तिकान

- पह्लवान दरदान सर्वान किरातान यवनाञ शकान (Mahabharata,3.48.20)

- हारहूणांश च चीनांश च तुखारान सैन्धवांस तदा

- जागुडान रमठान मुण्डान सत्री राज्यान अद तङ्गणान (Mahabharata,3.48.21)

Karna Parva/Mahabharata Book VIII Chapter 51 describes terrible massacre on seventeenth day of Mahabharata War and gives the list of Kshatriyas, who have been nearly exterminated in the van of battle. This includes Ramathas also. Thismay be reason of absence of this clan in present times.

- ..."the Tusharas, the Yavanas, the Khasas, the Darvabhisaras, the Daradas, the Sakas, the Kamathas, the Ramathas, the Tanganas the Andhrakas,...."

- उग्राश च करूरकर्माणस तुखारा यवनाः खशाः

- दार्वाभिसारा दरदा: शका रमठ तङ्गणाः (Mahabharata, 3.51.18)

Hukum Singh Panwar (Pauria)[15] gives us Tribal and Geographical Identifications based on India in Greece by E. Pococke, Indian Reprint, Oriental Publishers, Delhi-6. He gives at S. No. 69. Arcas/Ramatha who migrated from Afghanistan to Babylonia, where they were known as Arkas (Greece).

The conquests of Mahipala Pratihara (912-931 AD) are described in a grandiloquent verse by the poet Rajasekhara in the Introduction to his Play Balabharata or Prachanda Pandava, where Mahipala is said to be very axe to the Kuntalas ; and who by violence has appropriated the fortunes of the Ramathas. (See page-63 below) Thus both Mahabharata and Rajasekhara point out Ramathas in their neighbourhood.

We find very interesting information about Ramtha from Wikipedia at J. Z. Knight. Ramtha (the name is claimed to be derived from Ram and to mean "the God" in Ramtha's language) is an entity whom Knight claims to channel. According to Ramtha, he was a Lemurian warrior who fought the Atlanteans over 35,000 years ago.[16] Ramtha speaks of leading an army over 2.5 million strong (more than twice the estimated world population at about 30,000 BC) for 63 years, and conquering three fourths of the known world (which was going through cataclysmic geological changes). According to Ramtha, he led the army for ten years until he was betrayed and almost killed.[17]

Gotrachara and Genealogy

The Parihar gotra is found among the Rajputs, Jats and Gujars. They were the main Kshatriyas out of four Agnikula kshtriyas created in Mount Abu. Rajeshwara writes them Raghuvanshi on the basis of elder son Raghudeva of their ancestral king Nahara Deva (Nahadadeva I). The symbols of this dynasty are[18]:

- Gotra - Kaushika,

- Pravara - Vishvamitra, Kashaypa, Madhudandasa

- Mantra - Gayatri

- Veda - Yajurveda

- Upaveda - Dhanurveda

- Shakha - Vajasnehi

- Sooksha - Paraskara Griha Sooksha

- Kuladeva - Ramachandra

- Kuladevi - Pitambara/Chamundadevi

- Nadi - Sarasvati

- Teertha - Chitrakuta

- Nishana - Sun marked Red flag

- Pakshi - Garuda

- Vriksha - Shirisha (Pipal)

Pratiharas consider them Suryavanshi. First kingdom of Parihara vansha was Karapatha, which was handed over to Angada by Rama. Angada's descendants ruled for thousand years and rulers were: 1. Suchita, 2. Suchita, 3. Bharata, 4. Devajita, 5. Brahma, 6. Indradhruma, 7. Indrabhagna, 8. Parameshthi, 9. Sudhanva etc. In their 64th generation was Raghu. The descends of Ragu were 64. Raghu, 65. Aja, 66. Dasharatha, 67. Rama, 68. Lavakusha, Angada, Chitraketu, Pushkara, Subahu and Surasena 69. Atithi, 70. Nishadha, 71 Nala, 72. Nabha, 73. Pundarika, 74. Kshemadhandha, 75. Devanika, 76. Ahinagu, 77. Rupa, 78. Rura, 79. Paripatra, 80. Dala, 81. Chhala, 82. Ukatha, 83. Suvarga, 84. Kumutrijita, 85. Brahmadaja, 86. Dhami, 87. Kritanjaya, 88. Rananjaya, 89. Sanjaya, 90. Shakya, 91. Suddhodana, 92. Ratula, 93. Prasenajita, 94. Kshudra, 95. Kundaka, 96. Suratha, 97. Sumitra etc.

Starting from Angada to Chandraketu and Harichandra there was a period of thousands of years. Chronological ancestry is not available. After Mahabharata we get history of Parihara Rajavansha of Dhanyadesha.

The King Ajarana founded kingdom named Gurjartra on the banks of River Narmada and founded the city Nagaur. His son Nahada Rao repaired the Pushkara Tirtha and installed chaturmukhi Brahma Statue. Hence spread the rule of Pratiharas. [19] [20]

Early history

Earliest mention

D R Bhandarkar[21] provides us from Basantgarh Inscription of Varmalata of V.S. 682 (625 AD) - The second name is Pratihara Botaka, the first of which words I think signifies the race. Botaka was thus a Pratihara, i.e. Padiyar, and this is the earliest instance of the denomination Pratihara occurring in an inscription.

Jat History

Ram Swarup Joon[22] writes about Parihar, Prathihar, and Panwar: According to many writers they belong to the Gujar dynasty and their ancestors are said to have been associated with the Mauryan Jatti clan .

At the time of becoming Rajputs their capitals were in Bhinmal and Tirah.

According to the descriptions provided by Bal Clans, Prathihara and Maha Prathihara were titles only.

They may or may not be Gujars, but they are Chandravanshi and are descendants, of Yayati.

After the Agnikula ceremony they decided to forget their original roots in order to rise in status.

Dhaul-s and Bhakarwa-s belong to the Panwar clans.

जाट इतिहास:ठाकुर देशराज

ठाकुर देशराज[23] लिखते हैं.... परिहार : यह राजकुल जाटों के अन्दर आगरा-मथुरा के जिलों में पाया जाता है। परिहार नाम नहीं, किन्तु इस कुल (गोत्र) की उपाधि है। परन्तु वे इसी नाम से मशहूर हैं। इनकी उत्पत्ति के सम्बन्ध में पुराणों तथा अन्य ग्रन्थों में जो विचित्र बातें लिखी हैं, उनसे भी यही बात सिद्ध होती है कि परिहार उपाधि वाची शब्द है। कहा जाता है कि आबू के यज्ञ से सर्वप्रथम जो पुरुष पैदा हुआ, उसे प्रतिहार (द्वारपाल) का काम दिया। द्वारपाल होने के कारण ही वह परिहार कहलाया।

जाट इतिहास:ठाकुर देशराज,पृष्ठान्त-145

- दूसरे ढंग से यों भी कहा जाता है कि अश्वमेध यज्ञ के समय श्री लक्ष्मणजी द्वारपाल रहे थे, अतः उनके वंशज प्रतिहार अथवा परिहार कहलाये। राजपूतों में जो इस समय परिहार हैं, सी० वी० वैद्य ने उन्हें गूजरों में से बताया है, किन्तु गूजरों में जो परिहार हैं, वह कहां से आये, तथा यह नाम क्यों पड़ा, इसका निर्णय उन्होंने कुछ नहीं किया। डाक्टर भांडारकर तथा स्मिथ उन्हें विदेशी मानते हैं। उनका कहना है कि आबू में इन जातियों को आर्य-धर्म में दीक्षित किया गया । यह कथन उस हालत में मान लिया जाता जब कि परिहारों में जाटों का अस्तित्व न होता। जाट जाति के अन्दर उनका होना साबित करता है कि वे पहले से ही आर्य हैं और भारतीय हैं। क्योंकि आबू के यज्ञ से तो उन्हीं परिहारों का तात्पर्य है जो राजपूत हैं। यह सर्वविदित बात है कि जाट शब्द राजपूत शब्द से पुराना है। आबू-यज्ञ वाली घटना सही है, किन्तु यह सही नहीं कि वे विदेशी हैं। यज्ञ द्वारा दीक्षित होकर गूजरों में से राजपूत बने हों तो भारतीय हैं और गूजरों में जाटों से गए हों तो भी भारतीय हैं। बौद्ध-काल में जितना समूह उनमें से राजपूतों में (आबू महायज्ञ के महोत्सव के समय) चला गया, वह राजपूत-परिहार और जो पुराने नियमों के मानने वाले शेष रह गए, वे जाट-परिहार और गूजर-परिहार हैं।

History

The history section is mainly based on Reference - R.C.Majumdar: "The Gurjara Pratiharas", Journal of the Department of Letters Vol.X, Calcutta University Press, 1923 The page numbers given in the text are from this book.

Pratiharas of Jodhpur

Our knowledge of this dynasty is based upon six inscriptions, viz.

- (I) Mandor (Jodhpur) inscription of Bauka of V.894 (837 AD) - It was published in J.R.A.S., 1894, p. 1 ff. The inscription is dated, but the portion containing the date has been variously interpreted. Thus Munsi Deviprasad, Dr. Kielhorn and Professor D. R. Bhandarkar read the date respectively as Samvat 940, 4, and 894. [24] We have accepted Prof. Bhandarkar's interpretation of the date as the correct one. The topic will be fully discussed in Ep. Ind.

- (II- VI) The five Ghantiyala inscriptions of Kakkuka S.V. 918 (861 AD). One of these was published in J.R.A.S., 1895, p. 513 ff. and the remaining four, in Ep. Ind., Vol. IX, p. 277 ff. Three of these five inscriptions bear the date Samvat 918. The other two have no dates.

We have following more inscriptions about Pratihara dynasty:

- Buchkala Inscription of Nagabhatta of V. S. 872 (815 AD)

- Sambhal Copper-Plate of Nagabhata II of V.S. 885 (828 AD) ==

- Daulatpura copper plate of Partihar Bhojadeva of V.S. 900 (943 AD

- Siyadoni Inscription of Devapala of V.S. 1005 (948 AD)

The inscriptions supply us with the following genealogy of a line of kings belonging to the Pratihara dynasty.

All the above names except that of Kakkuka occur in inscription of No. I Mandor. In the Ghantiyala inscriptions of the Pratihara Kakkuka dated in V.S. 918 some names are slightly modified, such as Silluka for Siluka and Bhilluka for Bhilladitya. As they trace only the line of descent, they omit the names of the three brothers of Rajjila and the brother of Tata. They add a new name to the dynastic list, viz., that of Kakkuka, the step-brother of Bauka. The inscriptions thus furnish us with a line of kings extending over twelve generations. Taking twenty-five years as an average for each generation, the total reign period of the dynasty would be about 300 years. As the known date of Kakkuka is Samvat 918 (861 A.D.), and that of his step-brother Bauka, Samvat 894 (837 A.D.),

[Page-8] the founder of the dynasty Harichandra may be placed at about 550 A.D.

The verse 9 of inscription No. I tells us that the four sons of Harichandra built a large rampart round the fort of Mandavyapura which was gained by their own prowess (nija-bhujarjjite). Mandavyapura must be the same as Mandor whence the stone bearing the inscription was probably brought to Jodhpur five miles to the south. It is thus proved that the Pratihara clan of had advanced as far south as Mandor in the heart of Rajputana shortly after the middle of the sixth century A.D. This part of Rajputana is referred to in inscriptions of the ninth century A.D. as Gurjaratra, and must therefore be looked upon as a stronghold of the Gurjara power. It is permissible to hold, then, that the historic origin of the name is to be traced to the Pratihara clan of the Gurjaras which strongly established itself in the locality and ruled there for three hundred years up to the middle of the ninth century A.D. It is further legitimate to identify it with the Gurjara power to which various references are made in the records of the seventh century A.D. Let us discuss these one by one.

1) [Page-9] The Chinese traveller Hiuen Tsang visited a Gurjara kingdom which was about three hundred miles north of Valabhi. The direction and the distance lead us to the territory round Jodhpur over which Harichandra's dynasty was ruling at the time of the pilgrim's visit. There can be scarcely any doubt, therefore, that the Gurjara kingdom visited by Hiuen Tsang was the principality ruled over by the Pratihara line under consideration. Nay, I believe that we are even able to identify the king whose court was visited by the pilgrim. " The king' says he, " is of the Kshatriya caste. He is just twenty years old. He is distinguished for wisdom and he is courageous. He is a deep believer in the law of Buddha and highly honours men of distinguished ability." (Beal, Vol. II, p, 270) Now, as the pilgrim visited the kingdom about 100 years after the foundation of the dynasty we may reasonably expect four generations of kings to have passed away during that period, and the young king may be looked upon as belonging to the fifth. On referring to the dynastic list we find king Tata occupying this position. The verses 14-15 of the inscription No. I inform us that the king Tata, considering life to be evanescent as lightening, abdicated in favour of his younger brother, and himself retired to a hermitage, practising there the rites of true religion. The curious confirmation about the religious fervour of the king who may be held on other grounds to have been a contemporary of the pilgrim gives rise to a strong presumption about the correctness of our identification.

It has been urged by Buhler and V. A. Smith that the kingdom visited by Hiuen Tsang was that of king Vyaghramukha, who belonged to the Chapa (चाप) dynasty1.

Note - 1. Chapal is a Muslim Jat clan found in Pakistan.

[Page-10] The theory rests upon the fact that Brahmagupta, the astronomer, who wrote his astronomical work Brahma-sphuta-siddhanta under the patronage of king Vyaghramukha of the Chapa dynasty, was known as Bhillamalavakacharya. It has been contended that Bhillamala which is thus proved to be the capital of Vyaghramukha, is identical with Pi-lo-mo-lo, the name given by Hiuen Tsang to the capital of the Gurjara kingdom visited by him and that the latter is therefore the principality ruled over by Vyaghramukha. Professor Bhandarkar has pointed out several drawbacks in this explanation. It will suffice here to point out that the identification of Pi-lo-mo-lo with Bhillamala is far from satisfactory in view of its distance from Valabhi as given by Hiuen Tsang. Besides, the Chavotakas1, who are looked upon as identical with the Chapas 2, are clearly distinguished from the Gurjaras in the Nausari Grant of the Gujarat Chalukya Pulakesiraja, and the Chapa kingdom cannot therefore be identified with the Gurjara kingdom visited by Hiuen Tsang.

(2) The feudatory Gurjara chiefs of Broach claim descent from a race of Gurjara kings (Garjara-nripa-vamsa). Now the earliest known date of the third of these chiefs is 629 A.D.. Allowing fifty years for the two generations that preceded him we get the date 580 A.D., for the feudatory (samanta) Dadda who founded the line. This date corresponds so very well with that of Dadda, the youngest son of Harichandra, that the identity

Notes - 1. Chapotkat (चपोत्कट) and 2. Chapu (चापू) both are in the list of Jat clans

[Page-11] of the two may be at once presumed. It has been already suggested, on general grounds, that the Broach line was feudatory to the main line of the Gurjaras further north, and the proposed identification shows that the main Gurjara power in the north was the Pratihara line under consideration. An important piece of evidence in support of this has recently been brought to light by Mr. A. Venkata Subbiah. We learn from the colophon and the opening stanzas of the commentary known as Laghuvritti on Udbhata's Kavyalamkarasamgraha, that it was written by Induraja, who was a Pratihara and an inhabitant of Konkana. This goes a great way towards proving that the Gurjara rulers of Broach belonged to the Pratihara clan.

(3) It is recorded in the Aihole inscription (EI, VI,p.1) that the Latas, Malavas and the Gurjaras submitted to the Chalukya hero Pulakesi II. The Gurjaras must here be taken to refer to the Pratihara dynasty under consideration, for it cannot denote the feudatory line founded by Dadda as it is included under the Latas. The mention of the Gurjaras along with the Malavas and the Latas clearly show that they occupied a territory contiguous to these two provinces, and the kingdom of the Pratihara line under consideration exactly corresponds to this.

(4) Banabhatta refers to Prabhakaravardhana's successful wars against the Gurjaras. Prof. D. R. Bhandarkar has shown, on general grounds, that the Gurjaras in this passage must refer to those in Rajputana. This conclusion is supported by another consideration. The feudatory Dadda II of Broach is said to have protected a lord of Valabhi against the Kanauj emperor. Surprise has

[Page-12] justly been expressed how a small state like Broach could withstand the force of the mighty emperor. Everything however appears quite clear if we admit Broach to have been a feudatory state of the dynasty of Harichandra and remember its hereditary enmity with the royal house of Thaneswar. That the Gurjaras were not worsted in their struggles with Thaneswar kings appears quite clearly from the fact that they retained their independence, as Hiuen Tsang informs us, till at least a late period in the reign of Harshavardhana. The struggle between Dadda II and the rulers of Kanauj, incidentally referred to in inscriptions, may thus be looked upon as an episode in the long-drawn battle between the two powers. The various inferences to the Gurjaras in the records of the seventh century A. D. may thus be held to apply to the Pratihara line under consideration. It may of course be argued, in the absence of pompous and high- sounding titles in the inscriptions of this line of rulers, that they were only small feudatory chiefs; but the contention can hardly be maintained in view of the fact that in this respect our inscription No. I bears a close resemblance to the Gwalior inscription of the emperor Bhoja. Inscription No. I applies the term rajni to Bhadra, the queen of Harichandra, and to Jajjikadevi, the queen of Nagabhata, and the term maharajni to Padmini, the queen of Kakka. It refers to the rajadhani of Nagabhata and the rajya of Tata, Jhota and Bhilladitya.

[Page-13] The sons of Harichandra are called Bhudharanakshama (भूधरणक्षम), Kakka is styled bhupati, and Bauka is called nripisimha. The Gwalior inscription gives no royal epithet to Nagabhata, the first chief, calls the second and fourth chiefs respectively as kshhabhridisha and kshmapala, while Nagabhata II and Bhoja, the greatest kings of the dynasty are introduced without any royal epithet. Whatever might be the reasons, the close parallel between these two contemporary records would preclude any conclusion regarding the subordinate rank of the chiefs under consideration on the ground of the absence of high sounding royal epithets. It may also be observed in this connection that the inscriptions do not assign any such subordinate titles to these rulers as are used by the feudatory Gurjara chiefs, and this contrast between the two lines of rulers undoubtedly testify to the fact that the Pratihara rulers under consideration were independent and not subordinate. Having discussed these preliminary points we are now in a position to reconstruct the history of the Pratihara rulers of Rajputana. It would appear that towards the middle of the sixth century A.D., the Gurjaras advanced from their settlements in the Punjab towards the heart of India. The period was indeed a suitable one for their conquering expeditions. After the downfall of the short-lived empires of Yasodharman and Mihirakula, Northern India must have presented a favourable field for the struggle of nations, and the Gurjaras thus found a favourable opportunity to press forward. It may be readily imagined that their advance towards the east was checked by the rising power of the ruling house of Thaneswar, and

[Page-14] that was probably the origin of the hostility between the two powers. In the south, however, there was no great power to oppose any successful resistance to them, and hence they were able to make rapid advances in this direction. Harichandra must have been the leader or at least one of the principal leaders of this advanced section of the Gurjaras ; in any case his family emerged as the most powerful of the clan and established itself in the territory now roughly represented by the Jodhpur State.

Wives of Harichandra: We possess some information about this Harichandra from inscription No. I. He was a brahmana, versed in the Vedas and other Shastras and is described as a preceptor like Prajapati. It is interesting to note that he married two wives, one from a Brahmana and the other from a Kshatriya family. The sons, " born of the brahmana wife, became Pratihara Brahmanas," "while those born of the Kshatriya, the queen Bhadra," became the founders of the royal line of the Pratiharas. A word of explanation is given in inscription No. I as regards the origin of the name Pratihara. This, added to what we learn from the Gwalior inscription of Bhoja, informs us that the clan claimed descent from the epic hero Lakshmana, and the fact that he served as a door-keeper (pratihara) to his brother Rama on a memorable occasion, gave rise to the epithet assumed by it. All these serve to

[[Page-15] show the great extent to which the Gurjaras had imbibed the culture of the land in their settlements in the Punjab. Then, again, it is significant that the Kshatriya wife of Harickandra is called a queen, while no such royal epithet is added to his Brahmana wife. The fact possibly was, that Harichandra, versed in the Sastras, began his life as a preceptor in one of the peaceful settlements of the Gurjaras in the Punjab; but when the tribes once more resumed their military campaign, his racial instincts triumphed over the veneer of his borrowed culture and he changed the Sastra for the Shastra. He proved to be the most successful military leader among the Gurjaras and established a royal line that kept alive his name and fame for generations to come. The onward rush of the Gurjaras was not stopped with the death of Harichandra. The verse 9 of inscription No. 1 informs us that his sons conquered Mandavyapura (Mandor) and built a fortress there, to keep the enemies in check. (Cf. Verse 9 of the Jodhpur inscription of Pratihara Bauka.) Again, we are told in verse 12 of inscription No. 1 that Nagabhata, the fourth king, fixed his capital at the large city of Medantaka (Cf. verse 12 of the Jodhpur inscription. J.R.A.S., 1894, p. 3.), which has been identified by Munshi Deviprasad with Merta, 120 miles north-east of Mandor. The territory round Mandor is almost due south from the Gujarat and Gujranwala districts of the Punjab. It may be held, therefore, that the Gurjaras proceeded, generally speaking, towards the south from these strong- holds. Their gradual advance in this direction ultimately led them across the Nerbudda as far as the river Kim, and possibly even beyond it. Our knowledge about the

[[Page-16] different stages of this extensive conquest is as yet imperfect, but some main facts may be brought out by a study of the contemporary records. As has already been noted above, these southern territories were ruled in the seventh century A.D. by a feudatory line of Gurjara chiefs who traced their descent from Samanta Dadda. This person I have already identified with Dadda, the son of Harichandra. It is legitimate to infer, that, adopting a practice afterwards followed by both tho Chalukyas and the Rashtrakutas, Rajjila created a feudatory principality in the south under his younger brother Dadda, evidently as a check against the rising power of the Valabhis and the Chalukyas. Altogether six rulers of this line are known to us, viz., Dadda I, Vitaraga- Jayabhata I, Prasan-taraga-Dadda II, Jayabhata II, Bahusahaya-Dadda III, and Jayabhata III, each of these being the son of his predecessor. The earliest records of the family, dated 629 A.D. and 641 A.D., belong to the time of Dadda II, and we possess also several grants of the last king Jayabhata III dated 706 and 736 A.D. The identification of the villages mentioned in these grants enables us to form an estimate of the extent of the feudatory Gurjara principality. As Dr. Fleet remarks, " these records cover the country from the north bank of the river Kim to the south bank of the Mahi, and so show the extent of the Gurjara territory in the neighbourhood of the coast; inland it doubtless extended to the Ghats." Now, it is a noticeable fact that all these territories belonged to the Katachchuris or Kalachuris. The Sankheda (संखेडा) Grant of Shantilla (शांतिल्ल)(EI, II, p.21) shows that the territory round Dabhoi were ruled by Nirihullaka, a feudatory of Sankaragana.

[Page-19] There can be scarcely any doubt that the Gurjaras in Lata were able to hold their own against the royal houses of Thaneswar, Valabhi and Badami simply because they were backed by the main power of the Pratihara ruling family at Medantaka. For, otherwise it is difficult to explain how such a small principality could manage to maintain its independent existence against such powerful foes. We have already referred above to the first four kings of this main dynasty.

Confederacy of clans under the Bhattis

Verses 13-17 of inscription No. I describe the next four kings, of whom, however, nothing of particular importance is known. The next king Shiluka is described in verses 18-20. The verse 18 tells us that he fixed the perpetual boundary of the provinces of Travani and Valla. Now these two provinces, along with a few others are said to have been included in the territories of Kakkuka, the 14th king

[Page-20] of the dynasty. It may be held, therefore, that there was some disturbance in the kingdom. That some danger had befallen it is also implied in the next verse wherein we are told that the protector of Vallamandala gained the confederacy of the Bhattis by overthrowing Devaraja. (भट्टिकं देवराजं यो वल्लमण्डल-पालक: | नि(पा)त्य तत्ख(?)नम् भूमन प्राप्तवान-च्छत्र-चिह्नक: || V.19 Jodhpur Inscription)

These verses which occur in the Ghantiyala inscriptions of Kakkuka seem undoubtedly to imply that Kakkuka ruled over the countries mentioned therein. Prof. D. B. Bhandarkar holds the same view in J. Bo. Br. R. A., S., Vol. XXI, p. 414. For the identification of the countries see Ep. Ind , Vol. IX, p. 278.

Here the, Bhattis seem to be the name of the sab-clan to which the rulers belonged, for in verse 26 of inscription No. I, Padmini the queen of Kakka, is said to be the purifier of the Bhatti clan. These facts, by themselves alone, are not easy to understand, but when taken along with other known facts, they yield interesting information. These facts are :

(1) The Arab raids.

(2) The rise of a new ruling dynasty among the Pratiharas.

(I) It is a well known fact that the Arabs had established themselves in Sindh at the beginning of the eighth century A.D. and used to send military expeditions into the interior from time to time. The Nausari plates of the Gujarat Chalukya Pulakesiraja, dated in 738 A.D., refers to an expedition of the Arabs in course of which they are said to have defeated the kings of the Saindhavas 1, the Kachchhellas 2, Saurashtra 3, the Chavotakas 4, the Mauryas 5and the Gurjaras 6. It seems very likely that the Arab invasion referred to in the grant was that undertaken by the officers of Junaid, the general of Kalif

Notes - 1. Sindhu (सिंधु), 2. Kachela (काचेला), 3. Sorout (सोरोत), 4. Chapotkat (चपोत्कट)/ Chapu (चापू), 5. Maurya (मौर्य) / Mor (मोर), 6. Gurjara (गूर्जर) are all in the list Jat clans

[Page-21] Hasham (724-743 A.D.). Biladuri gives a short account of these expeditions, and mentions, among other things, that Junaid sent his officers to Marmad, Mandal, Barus and other places, and conquered Bailaman and Jurz. (Elliot, History of India, Vol. I, p. 126) There can be no doubt that Marmad is the same as Maru-Mara which is referred to in the Ghatiyala inscription No. II above, and includes Jaisalmer and part of Jodhpur State. (Ep. Ind., Vol. IX, p. 278) Barus is undoubtedly Broach, and Mandal probably denotes Mandor. It is now a well known fact that Jurz was the Arabic corruption of Gurjara. Bailaman probably refers to the circle of states referred to in inscription No. I, as Valla-Mandala. It would thus appear that the Arabian army under Junaid conquered the main Gurjara states in the north as well as the feudatory state of Broach in the south. This catastrophe must have taken place about the beginning of the second quarter of the eighth century A. D. According to Biladuri, the Arab expeditions were arranged by Junaid during the Caliphate of Hasham who ruled from 724 to 743 A.D. According to Elliot Junaid was succeeded by Tamim about 726 A.D. (Elliot, History of India, Vol. I, p. 442) Evidently this last date is far from being definitely known and we may therefore conclude that the expeditions were undertaken shortly after 724 A.D. The Nausari plates show, however, that the expeditions referred to in them took place between 731 A. D. and 738 A. D. For, according to the Balsar plates, Avanijanashraya Pulakesiraja did not come to the throne till the year 731 A. D. and as he himself takes the credit of having repelled the Arabs from Nausari the event must be dated after that year. Now Biladuri tells us that besides the Gurjara territories

[Page-22] noted above Junaid sent officers against Ujjain, and against the country of Maliba (evidently meaning the eastern and western Malwa), but Junaid's successor was feeble and in his days the Musulmans retired from several parts of India, and left some of their possessions. (Elliot, History of India, Vol. I, p. 126) If we consider together the information supplied by the Indian inscriptions and the Arab historians, we may safely conclude that the Arab expeditions which began shortly after 724 A. D. lasted for a period of about ten years. During the first part of this period, under the direction of Junaid, the Arabs achieved great successes and overran the neighbouring provinces as far as Ujjain in the east and Lata in the south. But the force of the first onward rush was soon spent up, and under Tamim, the feeble successor of Junaid, they had to retire from their newly conquered territories. In the south they were defeated by the Gujarat Chalukyas under Avanijanashraya Pulakesiraja, while in the east they met with a new power which not only checked their present aggressions but was destined to prove one of the strongest bulwarks against the advance of the Islamic power in future. This was the Pratihara dynasty of Avanti, of which we next proceed to give some detailed account.

(2) It has been already noticed above that the Gurjaras advanced southwards from the Punjab till they settled in and about Mandor in Rajputana, and that from this place they not only continued to advance towards the south but also moved towards the east. The available evidence shows that they settled in various parts of the country in both these directions. Thus Dr. V. A. Smith has

[Page-23] shown that there are consistent traditions, current in different parts of Bundelkhand, to the effect, that the Pariharas settled there about the eighth century A. D. Towards the south their occupation of Lata has already been referred to and it is not impossible that they proceeded even further south ; for Mr. A. Venkatasubbiah has traced the existence of Pratihara chiefs even in the Kanara country.

Pratihara kingdom in Ujjain

But by far the most important settlement in this direction was that of Avanti, or western Malwa, for the Pratihara chiefs of this place were the founders of the great imperial family at Kanauj. This fact, so far as I know, has not been recognised by any historian, but it seems to me to rest on unimpeachable grounds. I shall therefore deal with the question in some detail. Mr. K. B. Pathak brought to light a passage in Jaina Harivamsa of Jinasena which gives the precise date of its composition. The passage was subsequently noticed by Peterson and Fleet (Ep, Ind., Vol. VI, pp, 195.6) and the following remarks of the last named scholar may be taken to fairly represent the views of all the three regarding its interpretation. " A passage in Jaina Harivamsa of Jinasena tells us that the work was finished

[Page-24] in Saka-Samvat 705 (expired), = A. D. 783-784, when there were reigning, in various directions determined with reference to a town named Vardhamanapura (वर्धमानपुर), which is to be identified with the modern Wadhwan (वढवाण) in the Jhalawar division of Kathiawar, in the north, Indrayudha ; in the south Srivallabha ; in the east, Vatsaraja, king of Avanti (Ujjain); and, in the west, Varaha or Jayavaraha, in the territory of the Sauryas."

This seems to have been the accepted view till 1902 when Prof. D. R. Bhandarkar gave a somewhat different interpretation of the passage. " The second half of the stanza," said he, " beginning with sakeshv-abda-sateshu, etc., does not appear to me to have been properly translated. The word nrpipa in my opinion, shows that Avanti-bhubhriti is to be connected with purvam and Vatsadiraje with aparam. The translation would then be as follows : " in the east, the illustrious king of Avanti ; in the west king Vatsaraja (and) in the territory of the Sauryas, the victorious and brave Varaha."

Dr. V. A. Smith writing in 1909, accepted the interpretation of Prof. Bhandarkar with the prefatory remark " that the translation has been the subject of dispute." Later on Mr. R. Chanda, Mr. R. D. Banerji and Sten Konow accepted the translation given by Prof. Bhandarkar, which may thus be said to have held the field till now. In my humble opinion, however, the views of Fleet and Pathak seem to be preferable. For, in the first place, the author evidently seeks to describe the four kings in the four directions; but according to Prof. Bhandarkar's view, apart from grammatical difficulties, there being no object of the verb avati, -we

[Page-25] get a fifth province and there remains no name for the king of the east, the only exception of the kind. Secondly, as the writer was indicating these directions with reference to Vardhamanapura, modern Wadhwan, in the Jhalawar division of Kathiawar, " the west " can only refer to Saurashtra and cannot be taken to apply to a country like Gurjaratra or even to any part of Rajputana where Vatsaraja is supposed to have been ruling. According to the interpretation of Dr. Fleet, Vatsaraja, the king of Avanti, would be the king of the east, and king of Saurya or Sauramandala, evidently Saurashtra, the king of the west, referred to by the author. It will be observed that this is fully in keeping with the geographical position of Wadhwan, where the author wrote his book. Quite recently, Prof. D. R. Bhandarkar has drawn my attention to a passage in an unpublished copper plate grant in his possession, which runs as follows:

- Hiranyagarbham rajanyaih Ujjayinyam yada==sitam |

- Pratihari(h) kritam yena Gurjjares = adi rajakam ||

This points to a Gurjara Pratihara kingdom in Ujjain, for the word Pratihara, apart from its usual meaning, is evidently an allusion to the name of the clan. Professor Bhandarkar admits that this finally settles the point, in regard to the interpretation of the passage in Harivamsa, in favour of Pathak, Peterson and Fleet. Now, an account of the Pratihara dynasty to which this Vatsaraja, King of Avanti, belonged, has been

[Page-26] preserved in the Gwalior inscription of Bhoja. It tells us that, Nagabhata, the founder of the family, defeated the powerful forces of a Mlechchha king. (Gwalior inscription, verse 4). The manner in which this solitary fact is mentioned with regard to the founder of the royal line seems to show that it was looked upon as of great importance in the history of the family. Now the locality of Nagabhata's kingdom and the period when he flourished, may be gathered from the passage in the Jaina Harivamsa referred to above. It has been unanimously held by scholars that the Vatsaraja, referred to in the above passage, is the Pratihara king of the same name, the grand-nephew of Nagabhata. As Vatsaraja was ruling in 783-784 A. D., Nagabhata may be taken to have flourished about 725 A.D. Again Avanti must be looked upon as the home territory of the dynasty, for although Vatsaraja ruled over an extensive kingdom, he is called the ruler of Avanti in the above passage. It may be held therefore, that Nagabhata was ruling over Avanti about 725 A. D. As we have seen above this was the period when the great Arab raid took plans, and Biladuri clearly mentions Uzain as being attacked by the Arabs. Uzain is no doubt the same as Ujjain, the capital of Avanti and there can scarcely be any doubt, therefore, that the Gwalior inscription, like the Nausari plates, refers to the Arab expedition described by Biladuri. According to tho Gwalior inscription of Bhoja, the Arab forces were defeated by Nagabhata and this is fully

[Page-27] in keeping with the account of Biladuri, who observes : " They (i.e., the Arabs) made incursions against Uzain, and they attacked Baharimand and burnt its suburbs. Junaid conquered Al Bailaman and Jurz " Thus whereas other places were conquered, the Arabs merely sent incursions against Ujjain, and if we remember that this is from the pen of an Arab historian, it must be looked upon as a tacit admission that the Arabs failed in their expedition against Ujjain. It is also significant that the Nausari plates do not include the king of Avanti among the list of those that were defeated by the Arabs. We are now in a position to follow intelligently the account of the Pratihara dynasty of Jodhpur. It is possible that from the very beginning their kingdom consisted of a number of feudatory principalities which together composed a Mandala. At least the expression Vallamandalapalaka, applied to one of the kings in verse 19 of inscription No. I, seems to show that they were looked upon as the head of the confederacy. The disruption of this confederacy must have been one of the disastrous consequences of the Arab expeditions by which the whole country was overrun. In any case the outlying principality of Lata does not seem to have been retained long, for 736 A.D. is the latest date obtained for the Gurjaras in this quarter. Siluka who occupied the throne in the second quarter of the eighth century A. D. seems to have been able to avert a total wreck of his empire, and preserved the provinces of Travani and Valla to his family. Fortunately for him the fury of the Arab invasions passed away in a few years ; but a new danger was ahead. The rival Pratihara line of Avanti had acquired prestige and renown by hurling back the

[Page-28] Islamic hordes from their frontier, and it was inevitable that they should seek to wrest the supreme power from the Jodhpur Pratiharas, whose power must have been considerably weakened by the recent reverses. As noticed above, the verse 19 of inscription No. I informs us that " Siluka, possessed of the sign of umbrella, gained the confederacy of the Bhattis by having defeated Devaraja." It appears to me that this Devaraja is identical with the king of the same name in the Avanti family, who was the nephew of Nagabhata. This assumption rests upon three grounds :

- (1) The contemporaneity of Siluka and Devaraja, both having lived about 750 A. D.

- (2) This Devaraja is described in the Gwalior inscription of Bhoja as having laid the foundation of the future greatness of his family by defeating other kings.

- (3) Vatsaraja, the successor of Devaraja, is said in the same inscription to have wrested the empire from the famous Bhandi clan. (Cf. verse 7 in the Gwalior inscription of Bhoja) It seems to me very likely that this famous Bhandi clan is no other than the Bhatti clan to which the Jodhpur Pratiharas belonged.

The whole history of the period may then be construed as follows with the help of the data referred to above. As we have seen, shortly after the beginning of the eighth century A. D., a Pratihara dynasty was ruling in Avanti or western Malwa. That this dynasty was closely allied to the ruling dynasty of Jodhpur admits of no doubt, for both possessed the common tradition of being

[Page-29] descended from Lakshmana the brother of Rama; both traced the common name Pratihara to the fact that the hero once served as a doorkeeper to his elder brother Rama ; and the two families contained such common names of kings as Kakkuka, Nagabhata and Bhoja, the first two of which are not to be met with anywhere else. It is not definitely known in what relation the new dynasty stood to the old one, and when it advanced as far as Western Malwa. It is not of course impossible that the same wave of conquest which brought the Gurjaras as far as Lata in the south also established another branch in Avanti, a little to the east of it. This supposition is strengthened by the consideration that both these territories belonged to the Katachchuris just when the Gurjaras were advancing from Rajputana. That the Katachchuris had to give way before the advanced hordes of the Gurjaras appears quite clearly from the occupation of Lata by the latter some time before 629 A.D., as has been already noticed above. It is quite probable that the conflict between the Gurjaras and the Katachchuris continued even after the occupation of Lata by the latter, till they had also wrested Western Malwa from their enemies. In the century, 625-725 A. D., then, the Gurjaras held sway over an extensive territory, and so far as is known to us at present, there was something like a confederacy of states over which the Pratihara family of Jodhpur ruled as suzerains. But then came the disastrous Arab invasions when the mighty Gurjara power lay prostrate before the vanguards of Islam. One of the Gurjara principalities, however, successfully withstood this terrible shock. The natural defences, as well as its remoteness might have contributed towards the result, but in any case the Gurjara-Pratihara ruler of Avanti hurled back the forces of Islam and probably also caused the ultimate retreat of the marauders not long afterwards. This triumphant

[Page-30] success of one of the Gurjara principalities must have sadly contrasted with the serious reverses sustained by others and in particular by the ruling family which had hitherto exercised the suzerain power. It was inevitable that the successful power should make a bold bid for the supreme position, and it was natural that the Gurjara states should favourably entertain this claim of one who had proved to be their true saviour. That explains the struggle between Devaraja of the new family, and Siluka, who possessed the sign of umbrella, i.e., hitherto held the supreme position. Devaraja was however defeated and Siluka regained, or rather retained his suzerainty over at least a part of the Gurjara states. The rising Pratihara power of Avanti was not, however, to be checked by a single reverse. Vatsaraja, the son and successor of Devaraja, continued the struggle, and at length "wrested the empire from the famous Bhandi clan." Thus passed away the glories of the family of Harichandra, after it had successfully ruled as suzerain power for about two hundred years. The altered condition of the family is faithfully reflected in inscription No. I. After describing the military exploits of Siluka, the poet tells us that " his son Jhota proceeded to the Bhagirathi " and his grandson Bhilladitya " possessed of satva qualities and disposed to austerities bestowed the kingdom on his son and proceeded to Gangadvara" (vv. 21-22). This seems to indicate that the Pratihara family of Jodhpur was politically insignificant during the latter part of the eighth century A. D. The history of the Gurjaras henceforth centred round the rulers of the Avanti line, and we shall therefore proceed with their history, touching only incidentally upon that of the older family. The early kings of this dynasty, their relation to one another and the known dates we possess

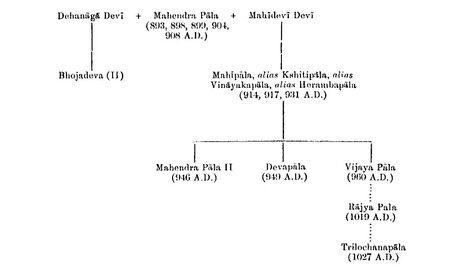

[Page-31] of them may be represented by the table as pictured.

The third king Devaraja is also known as Devasakti, and the seventh king is referred to under four different names such as, Mihira, Adivaraha, Prabhasa and Bhoja. Mahendrapala is called Mahendrayudha and Nirbhaya Narendra by his court poet Rajasekhara. The fifth verse of the Gwalior inscription may be taken to imply that the second king Kakkuka was also known as Kakustha.

We have already seen that Nagabhata, the founder of the family flourished about 725 A. D. and established its greatness by his triumphant success over the Arabs. The Hansot plates of the Chahamana feudatory Bhartrivaddha II (Ep Ind. Vol. XII, p. 197) records a grant that was made at Broach, in the increasing reign of victory of the glorious Nagavaloka, in the year 756 A.D. Prof. D. R. Bhandarkar upheld the view that this Nagavaloka is no other than Nagabhata I (Ind. ant., 1911, p. 240) and Dr. Sten Konow has accepted it. (Ep. Ind., Vol. XII, p 200) It

[Page-32] would then follow that he re-established the Pratihara suzerainty over Broach which the family of Jodhpur must have lost during the Arab expeditions. A reminiscence of Nagabhata's struggle with the neighbouring powers seems to have been preserved in the Ragholi plates of Jayavardhana II, a king of the Shaila (शैल) dynasty1 ruling over part of Central Provinces. We are told that Prithuvardhaua, a previous king of the family, conquered the Gurjara country. (EI,IX,p.41)

Practically nothing is known of the second king Kakkuka. The third king Devaraja is described in the Gwalior inscription as a very powerful ruler, wielding sovereignty over a number of chiefs. But, as noted above, he failed in his attempt to establish his suzerainty by defeating the Jodhpur Pratiharas. The cause of this failure is not far to seek. Almost at the same time when Nagabhata was laying the foundations of the future greatness of his family, a new power arose in the south. This was the Rashtrakuta dynasty of Malkhed. The Sanjan plates of Amoghavarsha informs us that king Dantidurga, the founder of the new power, conquered Avanti and performed a sacrifice in which a Gurjara king served as the Pratihari or door-keeper. (See the verse quoted above on p. 25.) This event possibly took place some time after 754 A.D., as it is not mentioned in the Samangad plates of Dantidurga, dated in that year. It is likely, therefore, that the Gurjara-Pratihara king who suffered defeat in the hands of the Rashtrakutas was Devaraja. Thus began that hereditary struggle between the two powers which lasted for about two hundred years. For the present, it must have considerably weakened the newly risen power. But

Note - 1. Shail (शैल) is a Jat clan

[Page-33] fortunately, confusion shortly broke out in the Rashtrakuta affairs, and a palace revolution placed Krishna I on the throne. Vatsaraja, the son and successor of Devaraja, was thus in a more favourable position than his father, and successfully accomplished the task left unfulfilled by the latter. He was undoubtedly one of the greatest heroes of the family and his reign constitutes a definite landmark in its history. The passage in Jaina Harivamsa, quoted above, definitely locates him at Avanti in the year 783-784 A.D., but, as a matter of fact, his power extended beyond its limits. The Gwalior inscription informs us that he took the empire from the Bhandis. As I have already indicated above this probably refers to his suzerainty over the Gurjara states in Rajputana. In any case, the Osia stone a inscription and the Daulatpura copper plate (Ep. Ind., Vol. V, p. 208.) clearly show that he exercised sway in Gurjaratra, in central Rajputana. We gather some important information about Vatsaraja from the Rashtrakuta records. The eighth verse

[Page-34] in the Radhanpur plates of Govinda III, which is also repeated in the Wani (वणी) grant of the same monarch refers to the defeat inflicted upon him by the Rashtrakuta king Dhruva in the following words :

- " By his matchless armies having quickly driven into the trackless desert Vatsaraja, who boasted of having with ease appropriated the fortune of the royalty of the Gauda, he in a moment took away from him, not merely the Gauda's two umbrellas of state, white like the rays of the autumn moon, but his own fame also that had spread to the confines of the regions." (Ep. lnd. t VI, 248.)

This passage certainly proves that Vatsaraja had defeated the King of Gauda, before he was himself defeated by Dhruva. It has been generally concluded that Vatsaraja invaded Gauda and must have of course conquered the intermediate states. This view, however, has probably to be given up in view of a verse in the Sanjan copper plate of Amoghavarsha I. It tells us with reference

[Page-35]: to Dhruva, that 'he took away the white umbrellas of the King of Gauda (who was) destroyed between the Ganges and the Jumna.' This verse seems to refer to an encounter between Dhruva and the King of Gauda somewhere between the Ganges and the Jamuna. That the Rashtrakuta king had actually proceeded so far in his career of conquest is also proved by a verse in the Baroda plates of Karkaraja. The important points established by these references may be summarised as follows :

- I. That the kingdom of Gauda stretched as far at least as Allahabad in those days.

- III. That, probably not long afterwards, Vatsaraja as well as the King of Gauda were defeated by Dhruva.

It appears that while Vatsaraja was laying the foundations of the future greatness of his family in the west, the Palas had established a strong monarchy in Bengal in the east. The former gradually expanded his kingdom towards the east while the latter did the same in the opposite direction. Under the circumstances it was inevitable that there would be a trial of strength between the two. In the first encounter the lord of Gauda was defeated; but while the rivals were thus fighting with

[Page-36] each other, a common enemy appeared from the south, involved both of them in a common ruin and pushed as far as the Ganges and the Jamuna. Thus began that tripartite struggle between the Gurjaras, the Palas and the Rashtrakutas which may be looked upon as the most important factor in the political history of India during the next century. The key-note of this struggle seems to have been the possession of the Ganges and the Jamuna, or more properly speaking, Kanauj, for which each of these tried and succeeded in his own turn. In order that the account of this struggle might be intelligently followed we arrange below, in a tabular form, the list of kings of the three rival dynasties, so far as we are concerned with them here.

| Gurjara | Rashtrakuta | Pala |

|---|---|---|

| Devaraja | Dantidurga (753 AD) | Gopala (770-780 AD) |

| Vatsaraja (783-784 AD) | Dhruva (779-794 AD) | Dharmapala (780-815 AD) |

| Nagabhata (815 AD) | Govinda III (794-814 AD) | ... |

| Ramabhadra | Amoghavarsha (811-877 AD) | Devapala (C. 815-850 AD) |

| Bhoja (843-890 AD) | ... | Vigrahapala (850-860 AD) |

| Mahendrapala (890-910 AD) | Krishna II (902 A.D.) | Nyarayapapala (860-915 AD) |

| Mahipaladeva (914-931 AD) |

It will appear from the above scheme that the first encounter took place between the Rashtrakuta king Dhruva, the Gurjara king Vatsaraja, and the Pala king Dharmapala But the death of Dhruva, sometime

[Page-37] before 794 A.D., ushered in a period of confusion in the Rashtrakuta kingdom. A confederacy of twelve kings in the south was formed against the new king Govinda III, and he had, besides, to cope with the treacherous hostility of the Ganga king. While his own hands were busy in the south the northern possessions seem to have been left in charge of his younger brother Indraraja. To the northern kings this was a good respite and they were not slow to take advantage of it. Dharmapala who was probably less affected by the Rashtrakuta blow, seems to have entered the field first and made his suzerainty acknowledged by almost all the important states in northern India including the Gurjara kingdom of Avanti. In particular, he conquered Kanauj by defeating Indraraja and others, and thus reached what seems to have been the goal of royal ambition in those days. The ever-shifting political combination of the time, however, made it difficult, if not impossible, for any king to enjoy undisturbed a long and prosperous reign. The Gurjara power was merely stunned by the Rashtrakuta

[Page-38] blow, not killed, and Nagabhata II, the son and successor of Vatsaraja, set himself to the task of retrieving the fortunes of his family. His achievements are described in four eloquent verses in the Gwalior inscription. By a careful examination of these as well as the data supplied by the Baroda plates of Karkaraja it is possible to form a fair idea of the history of his reign. It appears in the first place that Nagabhata II succeeded in allying himself with several other states. This follows from the statement in the Baroda plates that " by him (i.e., Indraraja, the Rashtrakuta ruler of Lata) alone, the leader of the lords of the Gurjaras, who prepared himself to give battle, bravely lifting up his neck, was quickly caused, as if he were a deer, to take to the (distant) regions ; and the array of the Mahasamantas of the region of the south, terrified and not holding together and having their possessions in course of being taken away from them by Shriballabha, through (shewing) respect obtained protection from him. (Ind. Ant., Vol. XII, p. 163) The same conclusion also follows from verse 8 of the Gwalior inscription." (V-8: Adyalj puman puna-rapi sphuta-kirttir asmaāj-jātas-sa eva kila Nāgabhatas-taākhyap, | Yattr-Andhra-Saindhava-Vidarbha-Kalivga-bhupaih kaannara-dhumni patanga-samair=apati ||) The poet tells us that kings of Sindhu, Andhra, Vidarbha and Kalinga succumbed to the power of Nagabhata as moths do unto fire. Now, moths are attracted by the glare of the fire and approach it of their own accord, although it leads to their ultimate destruction. The force of this simile is preserved if we suppose that the kings of the four countries were not conquered by Nagabhata but joined him of their own accord in the first instance although ultimately they lost their power thereby. The position of these four countries confirms this view. Joined to Avanti and the Gurjara states of Rajputana

[[Page-39] they form a central belt right across the country bounded in the north by the empire of the Palas, and on the south by that of the Rashtrakutas. It appears, therefore, to be quite likely that they formed a confederacy against the two great powers that pressed them from two sides, although, as so often happens, the most powerful member of the confederacy ultimately reduced the others to a state of absolute dependence. At the head of the confederacy thus successfully launched by him, Nagabhata tried his strength with both the rival powers. It is likely that he at first attempted to secure his position in the north by defeating the imperial schemes of the rival lord of Bengal, and like Dharmapala, he too first turned his attention towards Kanauj; for we are told in the Gwalior inscription of Bhoja that Nagabhata defeated "Chakrāyudha, whose lowly demeanour was manifest from his dependence on others." (Jitv-parshrayakrita-sphuta-nicha.bhāvam Chakrāyudham vinaya-i.amra-vapur = vyarājat V.9) As we know from the Bhagalpur plate of Narayanapala that Dharmapala placed one Chakrayudha on the throne of Kanyakubja after having conquered the place, it may be held as certain that the Chakrayudha, defeated by Nagabhata, was this very ruler of Kanyakubja who owed his throne to the favour of the Pala emperor. According to this point of view, Nagabhata's war against Chakrayudha was but a challenge to the emperor himself. The war between Nagabhata and the lord of Bengal is described in the tenth verse of the Gwalior inscription. Nagabhata is said to have achieved the victory, but the way in which the poet describes the array of the mighty hosts of the lord of Bengal (Durvvāra vari-vārana-vāji-vāra-yān-augha-samghatana-ghorā-ghan-andha kāram | Nirjitya Vangapatim.āvirabhud-vivasvān-ndyan-niva ttrijagadeka-Vikasako- yah ||) contrasts strangely with the " easy capture of the Gauda sovereignty " by Vatsaraja, and may be looked

[Page-40] upon as an index of the change that had come over Bengal in the intervening period. The battle probably took place at Monghyr, for the Jodhpur inscription of Bauka informs us that his father Kakka " gained renown by fighting with the Gaudas at Monghyr (Mudgagiri)." As Prof. D.R. Bhandarkar has shown, the inscription of Bauka is dated in 837 A.D.(Cf. verse 24, Jodhpur inscription of Pratihara Bauka). Kakka may be thus looked upon as a contemporary of Nagabhata, and as it does not appear likely that Kakka could lead an expedition up to Monghyr on his own account, it may be assumed that he accompanied his Gurjara overlord in his Bengal campaign. Another chief that probably accompanied Nagabhata on the same occasion was Vāhukadhavala, the feudatory chief of Surashtra. For we learn from an inscription of his great-grandson Avanivarman II (Ep. Ind., Vol. IX, pp.2 ff.) , a feudatory of Mahendrapaladeva, that he defeated king Dharma in battle, and as Kielhorn observes, this king Dharma may be identified with the Pala emperor of the same name. Kielhorn held that Vahukadhavala lived in the middle of the 9th century A.D., and was a feudatory of Bhoja (ibid p, 3). Dr. V. A. Smith (J.R.A.S., 1909, p. 266) and Mr. B. Chanda (Gauda-raja-mala p, 28) have supported this view. But as his great-grand-son was a feudatory of "Mahendrapala at the end of the ninth century A.D., it is more reasonable to hold, as Mr. R. D. Banerji has done (Banglar itihasa, p. 167) that Vahukadhavala was a feudatory of Nagabhata II at the beginning of the ninth century A.D. We can still trace a third chief who joined Nagabhata in his expedition against Bengal. This is Samkaragana, the Guhilot prince, referred to in the Chatsu inscription of Baladitya. (Ep. Ind., Vol. XV, pp. 10 ff.) It contains the following verse with reference to Samkaragana : Pratijnām prākkritro.dbhata-karighatā-samkata-rane bhatam jitvā Ganda- hshitipam = avanim samgara-hritām, | Balād-dāsim chakre (pra) bhu-charanayor=yah pranayimm tato-bhupah so-bhuj-jita-bahu-ranah Samkaraganah,|| (V.4.) Prof. D. R. Bhaadarkar who edited this inscription concluded from the above that Samkaragana conquered Bhata, the king of the Gauda country, and made a present of this kingdom to bis overlord. He farther suggested that this Bhata might be the same as Surapala. I beg to differ from these views of the learned scholar. The verse seems to me to mean that Samkaragana defeated the king of Gauda, a great warrior (Bhata), and made the whole world, gained by warfare, subservient to his overlord. Secondly, Samkaragana was the great-grand-son of Dhanika one of whose known dates is 725 A.D. (ibid, p. 11). Samkaragana, should, therefore, be taken as a contemporary of Nagabhata II and Dharmapala at the beginning of the ninth century A.D. The verse thus shows that Samkaragana helped his overlord Nagabhata to wrest the empire from Dharmapala by defeating the latter.

[Page-41] These scattered notices are sufficient to indicate the extensive preparations of Nagabhata against his adversary, and the very fact that he could advance as far as Monghyr seems to indicate that the ruler of Bengal was worsted in the fight. The simile by which the poet of the Gwalior inscription describes the triumph of Nagabhata seems to be a significant one. We are told that after defeating the dark dense array of the lord of Vanga, Nagabhata revealed himself, even as the rising Sun reveals himself by dispelling the dense darkness. This means, in plain language, that the rise of Nagabhata was possible only if he could defeat the king of Vanga and that explains why he first turned his attention in this direction. The Sun of Gurjara glory had set in with Vatsaraja, and the fortunes of his family, crushed by the lord of Vanga, lay enveloped in the darkness of night as it were, till a defeat inflicted by Nagabhata upon his enemy ushered in a new dawn for the Gurjaras. Soon the dawn passed away and the Sun reached its noonday height, for the next verse informs us that Nagabhata captured the strongholds of Anartta, Malava, Kirata, Turushka, Vatsa and Matsya countries. (Gwalior inscription of Bhoja I, verse 11. For the identification of the localities see J. R. A. S., 1909, pp. 257-8.) The poet leaves his hero at the height of his glory but it is quite clear from other records that the Sun had reclined tolhe west, and dusk set in, even in the lifetime of Nagabhata.

[Page-42] It has been already remarked above that the Rashtrakuta king Govinda III had been busy with turmoils in the south from the commencement of his reign, and it is undoubtedly to this fortunate accident that Nagabhata owed the respite which enabled him to carry on his brilliant military expeditions in the north. But the inevitable war between the two hereditary enemies broke out at last and we can gather some account of it from contemporary records. According to the Baroda plates of Karkaraja, Govinda III appointed Indraraja as the Governor of Latesvara-Mandala, which in my opinion denotes the whole of the northern possession of the Rashtrakutas. A passage in this inscription, already quoted above refers to a defeat inflicted upon the lord of the Gurjaras by Indraraja (alone). The lord of the Gurjaras seems undoubtedly to refer to Nagabhata, but the inscription of Avanivarman II, referred to above, puts up a claim on behalf of Vahukadhavala, a feudatory of the Gurjara king, that he defeated a Karnata army, meaning apparently the Rashtrakutas. (EI, IX, p. 3.) A comparison of these two statements leads to the inference, that even while Govinda III was engaged in the south, his governor of Lata had to feel the brunt of the Gurjara invasion under Nagabhata after the latter had strengthend himself by extensive conquests in tlie north. In the struggle which thus ensued each party claimed the victory, and there was probably no decisive result on either side. The situation was however completely changed when Govinda III, no doubt after settling his affairs in the south, hastened to the rescue of his brother. Once more

[Page-43] there was a trial of strength between the Gurjaras and the Rashtrakutas, but fortune was no more favourable to Nagabhata II than to his father. The result of this struggle is known from different sources. The Radhanpur plates of Govinda III inform us that when the Rashtrakuta monarch advanced towards the Gurjara king, the latter " in fear vanished nobody knew whither, so that even in a dream he might not see battle." (Ep. Ind., Vol. VI, p. 250.) Again, we learn from verse 22 of the Sanjan copper plate that Govinda III "destroyed the valour of Nagabhata and Chandragupta while he uprooted many other kings and again re-instated them." (Sa Nagabhata Candragupta-nripayor = yashauryam rane Svaharyyam = apaharyya dhairyyavikalan = ath = onmulayat. Sanjan plate, verse 22) According to the Pathari pillar inscription (Ep. Ind., Vol. IX, p. 248.) the Rashtrakuta chief Karkaraja defeated one Nagavaloka, and Prof. D. R. Bhandarkar perhaps rightly identifies this Nagavaloka with Nagabhata II and concludes that Karkaraja accompanied Govinda III in his expedition against the Pratihara king. (Ind. Ant., 1911, p. 239.) It would thus appear that Nagabhata II could not stand against the Rashtrakuta forces, although it is likely that he made good his retreat. But as verse 23 of the Sanjan copper plates imply, Govinda III overran his territory, and proceeded up to the Himalaya mountains. The Nilgund inscription (Ep. Ind. Vol. VI, p. 102.) informs us that Govinda III also fettered the Gaudas, and this is easily explained if we recall to mind how Dharmapala had provoked his hostility by attacking Indraraja, his younger brother, and governor in the north. The Sanjan plates, which contain much useful historical information not to be found anywhere else, are, however, much more explicit on the point. ---

[Page-44] We learn from these that Govinda III had proceeded up to Himalayas, and Dharmapala and Chakrayudha waited upon, or humbled themselves, of their own accord, to him. If we remember that both of them were defeated by Nagabhata II not long ago, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that they had made up their differences with the Rashtrakuta monarch by acknowledging his suzerainty in order to make a common cause against their more dangerous rival, viz., Nagabhata. This satisfactorily explains the advance of the Rastrakuta army up to the Himalayas although Nagabhata had not yet been worsted in an open battle. The date of this struggle admits of being more or less definitely settled by a comparison of the Want and the Radhanpur grants of Govinda III. The latter practically contains the same verses as the former with only a few additions and alterations ; and as the Gurjara conquest occurs in the additional part it may be assumed to have taken place between the dates of these two grants. Now, the Radhanpur grant is dated on the 27th July, 808 A D and the date of the Wani grant, although irregular, cannot be placed earlier than the 25th of April, 807 A. D. Thus Nagabhata II was defeated by Govinda III some time between 807 and 808 A D. The victory of the Rashtrakutas, although by no means final and "decisive, was no doubt disastrous to the Gurjaras. One of their late conquests, viz., the province of Malwa, passed into the hands of the Rashtrakutas and Andhra, Vidarbha and Kalinga also probably shared the same fate.

[Page-45] Pratiharas, however, did not cease to give trouble to the Rashtrakutas, for we are told in the inscription of the feudatory Karkaraja of Gujarat, that the Rashtrakuta king had " caused his arm to become an excellent door bar of the country of the lord of the Gurjaras. But the political situation changed. The Rashtrakutas themselves were torn asunder by internal dissensions. Karkaraja, the son and successor of Indraraja of Lata, was expelled by his younger brother in 812 A. D., and what was worse still, the revolutionary movement thus set on foot afterwards developed into an attempt to prevent the accession of Amoghavarsha I. This unexpected embroglio in the Rashtrakuta affairs left the Palas and the Gurjaras free to fight among themselves. It is difficult to follow in detail the course of this struggle which continued for more than a century, but a few prominent landmarks may be ascertained by a comparison of the records of the contending powers. The Bhagalpur copper plate of Narayanapala refers to Jayapala, the nephew of Dharmapala, in terms which seem to show that he defeated the enemies of Dharmapala in battles and made Devapala the supreme ruler of earth. Again the Monghyr copper plate of Devapala refers to his warlike expeditions up to the Vindhya mountains. This is fully supported by the Garuda pillar inscription of Badal according to which Devapala made the whole of northern India from Himalaya to Vindhya, and from the eastern to the western ocean tributary to him.

Pratiharas of Kannauj

This branch had the ancestry as under:

Harichandra (550 AD) → Nagabhata I (730–756) → Yashovarddhana → Vatsraja (775–805) → Nagabhata II (805–833) → Mihir Bhoja (Bhojadeva I) (836–886 AD) → Mahendrapala (885-912 AD) → Mahipaladeva (912-931 AD) → Vinayakapala I (931-943) → Mahendrapala II (943-948) → Devapala (948-959 AD) → Vijayapala (959-984) → Rajyapala → Trilochanpala (1019 AD) → Jasapala (1036 AD)

[Page-46] As regards the Gurjara Pratihara power, we learn from a Jaina book, Parbhavaka Charita, that king Nagavaloka of Kanyakubja, the grandfather of Bhoja died in 890 V. S., and this Nagavaloka has been rightly identified with Nagabhata II. (Ep. Ind., Vol. XIV, p, 179, fn. 3.) The Harsha stone inscription of Vigraharaja refers to him in terms which show that he was a very powerful king, and Guvaka I, the founder of the Chahamana dynasty was his vassal. (Ind. Ant. 1911, p. 239; Ep. Ind., Vol. II, p, 12.) Of Ramabhadra, the son and successor of Nagabhata II, we know very little, but that the Gurjara power declined during his reign is quite evident from the scattered notices we possess about him. Thus the Gwalior inscription of Vaillabhatta informs us that he had been the chief of boundaries in the service of Ramabhadra, and that his son occupied the office after him and was appointed to the guardianship of the fort of Gwalior by Bhoja. (Ep. Ind, Vol. I, pp. 154 ff.) This shows that during the reign of Ramabhadra and the early part of the reign of Bhoja Gwalior was the boundary of the Pratiharas. Again the twelfth verse of the Gwalior inscription of Bhoja (Ann. Rep. Arch. Sur t 1903-4, pp. 277ff.) seems to imply that Ramabhadra freed his country from the yoke of foreign soldiers who were notorious for their cruel deeds. It seems likely that ' the band of foreign soldiers by driving whom Ramabhadra got back the fame that was lost, even as Ramachandra recovered his Sita,' belonged to the Palas, for the other rival power, viz., the Rashtrakutas are not known to have advanced as far as the Gurjara kingdom at this period. The Daulatpura plates (Ep. Ind., Vol. V, p, 208,) also lead to the same conclusion. It renews the grant of a piece of land in Gurjaratra which was originally made by Vatsaraja and continued by Nagabhata II but had fallen into abeyance in the reign of Bhoja. This seems to indicate that the province was held by Vatsaraja

[Page-47] and Nagabhata II but lost by Ramabhadra and regained by Bhoja, sometime before 843 A. D., the date of the inscription. With the available evidence referred to above we are justified in tracing the course of the history of this period somewhat on the following lines. About 808 A. D. the Gurjara Pratihara power suffered a severe blow in the hands of the Rashtrakutas. Their rivals, the Palas, took advantage of this to establish their supremacy in northern India. Nagabhata retained his hold upon Kanauj which he had conquered from Chakrayudha, transferred his capital there and probably succeeded in offering an effective resistance to the Palas till his death in 833-34 AD. His successor Ramabhadra was a weak monarch and so the Pala emperor Devapala established his unquestioned suzerainty over northern India. His army advanced up to the Vindhyas and it was enough for Ramabhadra to have saved his own dominions. After a short and unsuccessful reign, the latter was succeeded by Bhoja about 840 A.D. Bhoja seems to have inherited the ambition of Vatsaraja and Nagabhata, and founded an empire for which his illustrious predecessors had tried in vain. A reminiscence of the struggles by which Bhoja thus regained his power in the north has been preserved in the Chatsu inscription of Baladitya. The Guhilot prince Harsharaja, the son of that amkaragana who accompanied Nagabhata II in his expedition against Bengal, is said to have conquered the kings in the north and presented horses to Bhoja, who has no doubt been rightly identified with the great Pratihara emperor Bhoja by Prof. D. R. Bhaudarkar. (Ep. Ind., Vol. XII, p. 12.) As Shankaragana was a contemporary of Nagabhata II, Harsharaja must have lived in the earlier years of Bhoja. It is therefore legitimate

[Page-48] to hold that the wars of Harsharaja were fought on behalf of the overlord Bhoja in the early years of the latter and enabled him to make extensive conquests in the north. Among others, as the Daulatpura copper plates seem to indicate, Gurjaratra was reconquered before 843 A. D. There are, however, good grounds for the belief that inspite of these early successes Bhoja's aspirations were at first doomed to failure. The Ghatiyala inscriptions of Kakkuka refer to the province of Gurjratra as being held by that king of the earlier Pratihara dynasty of Jodhpur. As this inscription is dated in 861 A. D. Bhoja must have lost the province between 843 and this date. It has been shown above that the province was held by Vatsaraja and Nagabhata, but lost by Ramabhadra, and regained by Bhoja before 843 A. D. This view entirely agrees with the condition of the Gurjara kingdom sketched out above as well as with the inscriptions of the Jodhpur Pratiharas. We have seen that there was a great decline of the Gurjara Pratihara power of Avanti after the defeat of Nagabhata II in the hands of the Rashtrakutas. Their difficulty must have offered the requisite opportunity to the Jodhpur Pratiharas to regain the power that they had lost. We have sketched their history up to the end of Shiluka's reign when the suzerain power was taken from them by Vatsaraja. We have also noted that the two successors of Shiluka are described as practising austerities an unmistakable proof of their political and military inanity. King Kakka, the third king after Siluka is however described as a great fighter and his queen consort is called a mahtirajni. (VV 24-26 of Jodhpur Inscription, J. R. A. S., 1894, pp. 1 ff.) Their son Bauka was also a great hero and his military exploits are described at great length in the Jodhpur inscription dated 837 A. D. Bauka was succeeded by