A glossary of the Tribes and Castes of the Punjab and North-West Frontier Province By H.A. Rose Vol II/B

| The full text of this book has been converted into Wiki format by Laxman Burdak |

Ba...

- Bab (बब) — A Muhammadan Jat clan (agricultural) found in Montgomery and Multan.

- Baba Lal Daryai (बाबा लाल दर्याई), a sect, followers of saddhu whose shrine is on the Chenab in the Wazirabad tahsil of Gujrdawala- and who miraculously turned water into food.

- Baba Lali (बाबा लाली), a follower of one of several Baba Lals. Baba Lal Tahliwala was a Bairagi of Pind Dadan Khan who could turn dry sticks into fihisham [tahli] trees. Another Baba Lal had a famous coutroversy with Dara Shikoh * Another Baba Lal had his headquarters at Bhera, and yet another has a shrine in Gurdaspur.

- Babar (बाबर). — A small tribe allied to the Sheranis — indeed said to be descended from a son of Dom, a grandson of Sherainai. They are divided into two main branches, Mahsand and Ghora Khel. The former are sub-divided into four and the latter into eight sub-divisions.

- The Babars are a civilised tribe and most of them can read and write.† They are devoted to commerce and are the wealthiest, quietest and most honest tribe of the sub-Sulaiman plains. Edwardes called them the most superior race in the whole of the trans-Indus districts, and the proverb says : 'A Babar fool is a Gandapur sage.' Intensely democratic, they have never had a recognised chief, and the tribe is indeed a scattered one, many residing in Kandahar and other parts of Khorasan as traders. A few are still engaged in the powinda traffic. The Babars appear to have occupied their present seats early in the 14th century, driving out the Jats and Baloch (?) population from the plains and then being pushed northward, by the Ushtarani proper. Their centre is Chaudwan and their outlying villages are held by Jat and Baloch tenants, as they cultivate little themselves.

- Babbar (बब्बर), a Jat tribe in Dera Ghazi Khan — probably immigrants from the east or aboriginal — and in Bahawalpur, where they give the following genealogy : —

- Raja Karan.

- ↓

- Kamdo.

- ↓

- Pargo.

- ↓

- Janjuban.

- ↓

- Khakh.

↓

- Babla (बबला). a section of the Bhatias, to which belong the chaudhris of Shujabad. Multan Gr, 1902, p. 166.

- Bachhal (बछल), a tribe of Jats, found in pargana Bhirug. Naringarh tahsil, Ambala : descended from a Taoni Rajput by his Jat wife.

- * This sect is noticed in Wilson's sects of the Hindus.

- † A Babar, the Amin-ul-Mulk Nur Muhammad Khan, was Diwan-i-Kul-Mamlakat to Taimiar Shah and gave a daughter to Shah Zaman Abdali. Four Babar families are also Settled in Multan : Gazetteer, 1901-02, p. 161

- Badechh (बदेछ), a tribe of Jats, claiming to be Saroa Rajputs by descent through its eponym and his descendant Kura Pal whose sons settled in Sialkot under Shah Jahan : also found in Amritsar.

- Badgujar/Bargujar (बड़गुजर), a class (or possibly rank) found among the Brahmans, Rajputs, Meos and possibly other tribes, as well as often along with Gujars. Thus the Bargujar Rajputs about Bhundsi in Gurgaon border on villages held by Gujars, and in one village there Gujars hold most of the village and Bargujar Rajputs the rest. Similarly in Basdalla near Punahana in Gurgaon Meos hold most of the village and Gujars the rest. (Sir J. Wilson, K.C.S.I., in P. N. Q. I., § 130). But according to Ibbetson, the Bargujar are one of the 36 royal Rajput families, and the only one except the Gahlot which claims descent from Lawa, son of Ram Chandra. Their connection with the Mandahar is noticed under Mandahar. They are of course of Solar race. Their old capital was Rajor, the ruins of which are still to be seen in the south of Alwar, and they held much of Alwar and the neighbouring parts of Jaipur till dipossessed by the Kachwdha. Their head-quarters are now at Anupshahr on the Ganges, but there is still a colony of them in Gurgaon on the Alwar border. Curiously enough, the Gurgaon Bargujar say that they came from Jullundur about the middle of the 15th century ; and it is certain that they are not very old holders of their present capital of Sohna, as the buildings of the Kambohs who held it before them are still to be seen there and are of comparatively recent date.

- Badhan (बधन) or Pakhai (पखई), a tribe of Jats, claiming Saroa Rajput origin and descended from an eponym through Kala, a resident of Jammu. Found in Sialkot.

- Badhaur (बधौर), an agricultural clan found in Shahpur.

- Badhi (बधी), the carpenter who makes ploughs and other rude wood-work among the Gaddis : (f r. badhna, to cut with an axe or saw). See Barhai.

- Badi (बादी), a gipsy tribe which does not prostitute its women. The word is said to be a corruption of Bazi-(gar) q. v. Cf. Wadia.

- Badohal (बदोहल), a tribe of Jats who offer food to their sati, at her shrine in Jasran in Nabha, at weddings ; also milk on the 9th sudi in each month. Found in Jind.

- Badozai (बदोजई), a Pathan family, found in Multan the Derajat and Bahawalpur State.

- Badu ( बदु), Baddun (बद्दुन), a gipsy tribe of Muhammadans, found in the Central Punjab, chiefly in the upper valleys of the Sutlej and Beas, Like the Kehals

they are followers of Imam Shafi* and by his teaching justify their habit of eating crocodiles, tortoises and frogs. They are considered outcast by other Muhammadans. They work in straw, make pipe-bowls, their women bleed by cupping and they are also said to load about bears and occasionally travel as pedlars. Apparently divided into three clans, Wahle, Dhara and Balara. They claim Arab origin. First cousins cannot intermarry. See Kehal.

- Badwal (बदवाल), a Rajput clan (agricultural) found in Montgomery.

- Bagdar (बगदर), a Baloch clan (agricultural) found in Montgomery.

- Baghban (बागवान), Baghwan, the Persian equivalent of the Hindi word Mali meaning a 'gardener,' and commonly used as equivalent to Arain in the Western Punjab, and even as far east as Lahore and Jullundur. The Baghbans do not form a caste and the term is merely equivalent to Mali, Maliar, etc.

- Baghela (बघेला), lit. "tiger's whelp," one of the main division of the Kathias, whose retainers or dependent; they probably were originally. Confined to the neighbourhood of Kamalia in Montgomery, and classed as Rajput agricultural.

- Bagiyana ( बगियाना), a Muhammadan Jat clan (agricultural) found in Montgomery.

- Bagrana (बगराना), a Baloch clan (agricultural) found in Montgomeri.

- Bagri (बागड़ी),† (1) a term applied to any Hindu Rajput or Jat from the Bagar (बागड़)or prairies of Bikaner, which lie to the south and west of Hissar in contradistinction to Deswala. The Bagris are most numerous in the south of that District, but are also found in some numbers under the heading of Jat in Sialkot and Patiala. In Gurdaspur the Bagri are Salahria who describe themselves as Bagar or Bhagar by clan and probably have no connection with the Bagri of Hissar and its neighbourhood. (2) a Jat clan (agricultural) found in Amritsar.

- Bahi, a tribe of Pathans which holds a bara of 12 villages near Hoshiarpur, (should be verified ?).

- * It is said that in the time of the Prophet there were four brothers, Imam Azam, Imam Hamil, Imam Shafi, and Imam Naik, aud Shaikh Dhamar, ancestor of the Badus, was a follower of this lmam Shafi. Once Shaikh Dhamar killed a tortoise, an act which was reprobated by three of the brothers, but Imam Shafi, approving his conduct the Shaikh ate the animal whereupon the three Imams called him had and hence his descendants are called Badu ! Such is the Badu legend, but the four Imams were were not brothers nor were they contemporaries of Prophet and Hamil is a corruption of Hampal.

- † It is doubtful whether Bagri is not applied to any Hindu or Muhammadan from Jaisalmer or Bikaner who speaks Bagri.

- Bahniwal(बहनिवाल), a Jat tribe, found chiefly in Hissar and Patidla. They are also found on the lower Sutlej in Montgomery, where in 1881 they probably returned themselves as Bhatti Rajputs, which they claim to be by descent. In Hissar they appear to be a Bagri tribe, though they claim to be Deswali, and to have been Chauhans of Sambhar in Rajasthan whence they spread into Bikaner and Sirsa. Mr. Purser says of them:— "In numbers they are weak; but, in love of robbery they yield to none of the tribes." They gave much trouble in 1857. In the 15th century the Bahniwal held one of the six cantons into which Bikaner was then divided.

- Bahoke (बहोके), a Kharral clan (agricultural) found in Montgomery.

- Bahrupia (बहरूपिया). — Bahrupia is in its origin a purely " occupational term derived from the Sanskrit bahu 'many' and rupa 'form' and denotes an actor, a mimic, one who assumes many forms or characters, or engages in many occupations. One of the favourite devices of the Bahrupias is to ask for money, and when it is refused, to ask that it may be given on condition of the Bahrupia succeeding in deceiving the person who refuses it. Some days later the Bahrupia will again visit the house in the disguise of a pedlar, a milkman, or what not, sell his goods without being detected, throw off his disguise, and claim the stipulated reward. They may be drawn from any caste, and in Rohtak there are Chuhra Bahrupias. But in some districts a family or colony of Bahrupias has obtained land and settled down on it, and so become a caste as much as any other. Thus there is a Bahrupia family in Panipat which holds a village revenue- free, though it now professes to be Shaikh. In Sialkot and Gujrat Mahtams are commonly known as Bahrupias. In the latter District the Bahrupias claim connection with the Rajas of Chittaur and say they accompanied Akbar in an expedition against the Pathans. After that they settled down to cultivation* on the banks of the Chenab. They have four clans — Rathaur, Chauhan, Punwar and Sapawat— which are said not to intermarry. All are Sikhs in this District. Elsewhere they are Hindus or Muhammadans, actors, mountebanks and sometimes cheats. The Bahrupias of Gurdaspur are said to work in cane and bamboo. The Bahrupia is distinct from the Bhand, and the Bahrupia villages on the Sutlej in Phillaur tahsil have no connection with the Mahtons of Hoshiarpur.† Bahrupias are often found in wandering gangs.

- Bahti (बाहती), a term used in the eastern, as Chang is used in the western, portion of the lower ranges of the Kangra Hills and Hoshiarpur as equivalent to Ghirth. All of them intermarry.

- Bahti (बहती), hill men of fairly good caste, who cultivate and own land largely; and also work as labourers. They are said to be degraded Rajputs. In Hoshiarpur (except Dasuya) and Jullundur they are called Bahti; in Dasuya and Nurpur Chang ; in Kangra Ghirth; all intermarry freely. In the census of 1881 all three were classed as Bahti. The Chang are also said to be a low caste of labourers in the hills who also ply as muleteers.

- * As cultivators they are thrifty and ambitious. They also make baskets, ropes and rope-nets — tranggars, and chikkas in Gujrat.

- † P. N. Q. I. § 1034.

- Baid (बैद), a got of the Oswal Bhabras, Muhial Brahmans and other castes : also a physician, a term applied generaly to all who practise Vedic medicine.

- Bains (बैंस), a Jat tribe, whose head-quarters appear to be in Hoshiarpur† and Jullundur, though they have spread westwards oven as far as Rawalpindi, and eastwards into Ambala and the adjoining Native States. They say that they are by origin Janjua Rajputs, and that their ancestor Bains came eastwards in the time of Firoz Shah. Bains is one of the 36 royal families of Rajputs, but Tod believes that; it is merely a sab-division of the Suryabansi section. They give their name to Baiswara, or the easternmost portion of the Ganges-Jamna doab. The Sardars of Alawalpur in Jullundur are Bains, whose ancestor came from Hoshidrpur to Jalla near Sirhind in Nabha some twelve generations ago.

Bairagi

Bairagi (बैरागी). — The Bairagi (Vairagi, more correctly, from Sanskrit vairagya, 'devoid of passion,') is a devotee of Vishnu. The Bairgis probably represent a very old element in Indian religion, for those of the sect who wear a leopard-skin doubtless do so as personating Nar Singh, the leopard incarnation of Vishnu, just as the Bhagauti faqir imitates the dress,†† dance, etc., of Krishna. The priest who personates the god whom he worships is found in 'almost every rude religion : while in later cults the old rite survives at least in the religious use of animal masks,'§ a practice still to be found in Tibet. There is, moreover, an undoubted pun on the word bhrag, 'leopard ', and Bairagi, and this possibly acfounts for the wearing of the leopard skin. The feminine form of Bairagi, bairagan, is the term applied to the tau-shaped crutch on which a devotee leans either sitting or standing, to the small emblematic crutch about a foot long, and to the crutch hilt of a sword or dagger. In Jind the Bairagi is said to be also called Shami.

The orders devoted to the cults of Ram and Krishn are known generically as Bairagis, and their history commences with Ramanuja, who taught in Southern India in the ll-12th centuries, and from his name the designation Ramamuji may be derived.‖ But it is not until the time of Ramanand, i.e., until the end of the 14th century, that the sect rose to power or importance in Northern India.

The Bairagis are divided into four main orders (sampardas , viz., Ramdnandi, Vishnuswami, Nimanandi and Madhavachari.

- * -Fancifully derived from baid, a pbysician — who rescued a bride of the clan from robbers and was rewarded by their adopting his name.

- † The Bains hold a barah or group of 12 (actuaily 15 or 16) villages near Mahilpur in this District.

- †† - Trumpp's Adi-Granth. p. 98.

- § Robertson Smith : Religion of the Semites, p. 437.

- ‖ -See Ibbetson, § 521 : where the Ramanujis are said to worship Mahadeo and thus appear to be Shaivas. Further the Bairagis are there said to have been founded by SriAnand, the 12th disciple of Ramanand. The termination nandi appears to be connected with his name. It is only to the followers of Ramanand or his contemporaries that the term Bairagis properly applied.

Of these the first-named contains six of the 52 dwaras* (schools) of these Bairagi orders, viz., the Anbhimandi, Dundaram, Agarji, Telaji, Kubhaji, and Ramsaluji.

In the Punjab only two of the four sampardas are usually found. These are (i) the Ramanandis, who like the Vishnuswamis are devotees of Ramchandr, and accordingly celebrate his birthday, the Ramnaumi,† study the Ramayana and make pilgrimages to Ajudhia : their insignia being the tar pundri or trident, marked on the forehead in white, with the central prong in red or white.

The only other group found in the Punjab is (ii) the Nimanandi, who, like the Madhavacharis, are devotees of Krishna. They too celebrate the 8th of Bhadon as the date of Krishna's incarnation, but they study the Sri Madh Bhagwat and the Gita, and regard Bindraban, Mathra and Dwarkanath as sacred places. On their foreheads they wear a two-pronged fork,††all in white.

In the Punjab proper, however, even the distinction between Rama and Nima-nandi is of no importance, and probably hardly known. In parts of the country the Bairagis form a veritable caste being allowed to marry, and [e.g.] in Sirsa they are hardly to be distinguished from ordinary peasants, while in Karnal many (excluding the sadhus or monks of the monasteries, asthal, whose property descends to their spiritual children§) marry and their hindu or natural children succeed them.‖ This latter class is mainly recruited from the Jats, but the caste is also recruited from the three twice-born castes, the disciple being received into his guru's samparda and dwara.¶ In some tracts, e.g. , in Jind, the Bairagis are mostly secular. They avoid in marriage their own samparda and their mother's dwara. In theory any Bairagi may take food from any other Bairagi, but in practice a Brahman Bairdgi will only eat from the hands of another Brahman, and it is only at the ghosti or place of religious assembly that recruits of all castes can eat together. The restrictions regarding food and drink are however lax throughout the order. Though the Bairagis, as a rule, abstain from flesh and spirits, the secular members of the caste certainly do not. In the southern Punjab the Bairagi is often addicted to bhang.

To return to the Bairagis as an order, it would appear that as a body they keep the jata or long hair, wear coarse loin-cloths and usually affect the suffix Das. As opposed to the Saniasis, or Lal-padris, they style themselves Sita-padris, as worshippers of Sita Ram.

- *It may be conjectured that the Valabhacharis, Biganandis, and Nimi-Kharak-swamis are three of these dwaras : or the latter term may be equivalent to Nimanandi. Possibly the Sita-padris are really a modern dwara. The Radha-balabhi, who affect Krishna's wife Radha, can hardly be anything but a dwara.

- † The 9th of Bhadon.

- †† Its shape is siid to be derived from the figure of the Nar Singh (man-lion) incarnation which tore Pralad to pieces.

- § Called nadi, is contradistinction to hindu children. Celibate Bairagis are called Nagas, the secular ghar-basi or ahirishi, i.e. , householders.

- ‖ It is not clear how property descends, e.g. it is said that if a guru marry his property descends on his death to his disciples, in Jind (just as it, does in Karnal. But apparently property inherited from the natural family devolves on the natural children, while that inherited from the quru descends to the chela. In the Kaithal tahsil of Karnal the agricultural Bairaigis who own the village of Dig are purely secular.

- ¶' But men of any caste may become Bairagis and the order appears, as a rule, to be recruited from the lower castes.

As regards his tenets a Bairagi is sometimes said to be subject to five rules : —

- (i) he must journey to Dwarka and there be branded with iron on the right arm :*

- (ii) he must mark his forehead, as already described, with the gopi chandan clay :

- (iii) he must invoke one of the incarnations of Krishna:

- (iv) he must wear a rosary of tulsi : and

- (v) he should know and repeat some mantra relating to one of Vishnu's incarnations.

Probably these tenets vary in details, though not in principle, for each samparda, and possibly for each dwara also.

The monastic communities of the Bairagis are powerful and exceedingly well conducted, often very wealthy, and exercise much hospitality. They are numerous in Hoshiarpur. Some of their mahants are well educated and even learned men, and a few possess a knowledge of Sanskrit.

The intense vitality of the Bairagi teachings maybe gauged from the number of sub-sects tn which they have given birth. Among these may be noted the Hari-Dasis (in Rohtak), the Kesho-panthist† (in Multan) the Tulsi-Dasis, Gujranwala, the Murar-panthis††, the Baba-Lalis.

The connection of the earliest form of Sikhism with the Bairagi doctrines is obscure, but it is clear that it was a close one. Kalladhari the ancestor of the Bedi family of Una, was also the predecessor of the Brahman Kalladhari mahants of Dharmsal in the Una tahsil, who are Bairagis, as well as followers of Nanak, whence they are called Vaishav-Nanak-panthi. This community was founded by one Nakodar Das who in his youth was absorbed in the deity while lying in the shade of a banyan tree instead of tending his cattle, and at last after a prolonged period of adoration, disappeared into the unknown. Another Bairagi, Ram Thamman, was a cousin of Nanak and is sometimes claimed as his follower. His tank near Lahore is the scene of a fair, held at the Baisakhi, and formerly notorious for disturbances and, it is said, immoralities. It is still a great meeting point for Bairagi ascetics. Further it will not be forgotten that Banda, the successor of the Sikh gurus, was, originally, a Bairagi, while two Bairagi sub-sects (the Sarndasi and Simrandasi§) arc sometimes classed as Udasis.

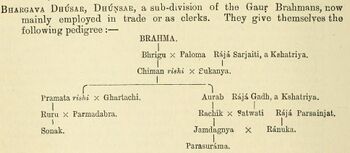

A modern offshoot of the Bairagis are the Charandasis, founded by one Charan Das who was born at Dehra in Alwar State in 1703.‖ His father was a Dhusar who died when his so-j, then named Ranjit Singh, was only 5. Brought up by relations at Delhi the boy became a

- * These brands include the conch shell (shankh) ,discus or Chakkar, club or gada, and lotus. Besides the iron brands (tapt mudara, lit. fire-marks) watermarks (sital mudra, lit. cold-marks) are also used. Further the initiatory rite, though often performed at Dwarka, may be performed anywhere especially in the guru's house. Some Bairagis even brand their women's arms before they will eat or drink anything touched by them.

- † probably worshippers of a local saint or of Krishna himself.

- †† Possibly followers of a Baba Murar whose shrine is in Lahore District, or worshippers of Krishn Murari, i.e., the enemy of Mura demon.

- § Sometimes said to be one and the same. Simran Das was a Brahman, who lived two centuries ago, and his followers are Gosains who wear the tulsi necklace and worship their gurus bed.

- ‖ Another account says he became Sukhdeo's disciple at the age of 10 in Sbt. 1708, 1651 A. D. For a full account of the sect see Wilson's quoted in Maclagan's, Punjab Census Report, 1891, p. 121.

disciple of Sukhdeo Das, himself a spiritual descendant of Biasji, in Muzaffarnagar, and assumed the name of Charan Das. He taught the unity of God, preached abolition of caste and inculcated purity of life. His three principal disciples, Swami Ram-rup, Jagtan Gosain and a woman named Shahgoleai ench founded a monastery in Delhi, in which city there is also a temple dedicated to Charan Das where the impression of his foot (charan) is worshipped.* His initiates are celibate and worship Krishna and his favourite queen Radha above all gods and goddesses. They wear on the forehead the joti sarup or "body of flame," which consists of a single perpendicular line of white†; and dress in saffron clothes with a tulsi necklace. The chief scripture of the sect is the Bhagat-sāgar, and the 11th day of each fortnight is kept as a fast. Charan Das is believed to have displayed miracles before Nadir Shah, on his conquest of Delhi, and however that may be, his disciples obtained grants of land from the Mughal emperors which they still hold.

Ba...

- Bairwal (बैरवाल), a tribe of Jats who claim to be descendants of Birkhman, a Chauhan Rajput, whose son married a Jat girl as his second wife and so lost status. The name is eponymous, and they are found in the Bawal Nizamat of Nabha.

- Baistola (बैस्तोला), a Jain sect : see Jain.

- Baizai (बैजई), one of the two clans of the Akozai Yusafzai. It originally held the Lundkhwar valley, in the centre of the northernmost part of Peshawar, and all the eastern hill country between that and the Swat river. It still holds the hills, but the Khattak now hold all the west of the valley and the Utman Khel its north-east corner, so that the Baizai only hold a small tract to the south of these last. Their six septs are the Abba and Aziz Khels, the Babozai, Matorezai, Musa and Zangi Khels. The last lies south of the Ilam range which divides Swat from Buner. Only the three first-named hold land in British territory.

- Bajarah (बजारह), One of the 15 Awan families descended from Kulugan, son of Qutb Shah: see History of Sialkot, p. 37.

- Bajwa (बाजवा), a Jat clan (agricultural) found in Sialkot, Amritsar and Multan, and as a Hindu Jat clan in Montgomery. The Bajwa Jats are of the same kin as the Bajju Rajputs.†† In Sialkot they have the customs of rasoa or lagan and bhoja twixt betrothal and marriage. The jathera of the Bajwa is Baba Manga, and he is revered at weddings, at which the rites of jandian and chhatra are also observed.

- Tlie Bajwa Jats and Bajju Rajputs have given their name to the Bajwat or country at the foot of the Jammu hills in the Sialkot District. They say that they are Solar Rajputs and that their ancestor Raja

- * Clearly there is some connection here with the Vishnupad or foot-impression of Vishnu.

- † It is also called simply sarup, or "body" of Bhagwan.

- †† It might be suggested that wā is a diminutive form.

Shalip was driven out of Multan in the time of Sikandar Lodi. His two sons Kals and Lis escaped in the disguise of falconers. Lis went to Jammu and there married a Katil Rajput bride, while Kals married a Jat girl in Pasrur. The descendants of both live in the Bajwāiit, but are said to be distinguished as Bajju Rajputs and Bajwa Jats. Another story has it that their ancestor Jas or Rai Jaisan was driven from Delhi by Rai Pithora and settled at Karbala in Sialkot. Yet another tale is that Naru, Raja of Jammu, gave him 84 villages in ilaqa Ghol for killing Mir Jagwa, a mighty Pathan. The Bajju Rajputs admit their relationship with the Bajwa Jats. Kals had a son, Dawa, whose son Dewa had three sons, Muda, Wasr, and Nana surnamed Chachrah. Nana'a children having all died, he was told by an astrologer that only those born under a chachri tree would live. His advice was taken and Nana's next son founded the Chachrah sept, chiefly found near Narowal. The Bajju Rajputs have the custom of chundavand and are said to marry their daughters to Chibh , Bhau and Manhas Rajputs, and their eons to Rajputs. The Bajju Rajputs are said to have had till quite lately a custom by which a Mussalman girl could be turned into a Hindu for purposes o£ marriage, by temporarily burying her in an underground chamber and ploughing the earth over her head. In the betrothals of this tribe dates aroused, a custom perhaps brought with them from Multan, and they have several other singular customs resembling those of the Sahi Jats. They are almost confined to Sialkot, though they have spread in small numbers eastwards as far as Patiala.

- Bakhri (बाखरी), a clan found in the Shahr Farid ilaqa of Bahawalpur. They claim to be Sumras by origin, and have Charan bards, which points to a Rajput origin. They migrated from Bhakhkhar to Multan, where they were converted to Islam by Gaus Baha-ud-Din Zakaria, and fearing to return to their Hindu kinsmen settled down in Multan as weavers. Thence they migrated to Nurpur, Pakpattan and other places, and Farid Khan I settled some of them in Shahr Farid from Nurpur. They make lungis. (The correct form is probably Bhakhri).

- Bakhshial (बख्शिआल), a family of Wahora Khatris, settled at Bhaun in Jhelum, which has a tradition of military service.

- Bakhtiar (बख्तिआर), a small Pathan tribe of Persian origin who are associated with the Mian Khel Pathans of Dera Ismail Khan, and now form one of their principal sections.

- Raverty however disputes this, and ascribes to the Bakhtiars a Sayyid origin. Shiran, the eponym of the Shirani Pathdns, gave a daughter to a Sayyid Ishaq whose son by her was named Habib the Abu-Sa'id, or 'Fortunate' (Bakhtyar). This son was adopted by his step-father Mianai, son of Dom, a son of Shiraz. The Bakhtiars have produced several saints, among them the Makhdum-i-'Alam, Khwaja Yahya-i-Kabir, son of Khwaja llias, son of Sayyid Muhammad, and a contemporary of Sultan Muhammad Tughluq Shah. He died in

- 1333 A.D., and his descendants are called Shaikhzais. Raverty says the Persian Bakhtiaris* are quite distinct from the Bakhtiars.

- Bakhtmal sadhs (बख्त्मल-साध), a Sikh sect founded by one Bakhtmal. When Guru Govind Singh destroyed the masands or tax-gatherers one of them, by name Bakhtmal, took refuge with Mata, a Gujar woman who disguised him in woman's clothes, putting bangles on his wrists and a nath or nose-ring in his nose. This attire he adopted permanently and the mahant of his gaddi still wears bangles. His followers are said to be also called Bakhshish sadhs, but this is open to doubt. The head-quarters of the sect appears to be unknown.

- Bal (बल), a Jat tribe of the Bias and Upper Sutlej, said to be a clan of the Sekhu tribe with whom they do not intermarry. Their ancestor is also said to have been named Baya Bal, a Rajput who came from Malwa. The name Bal, which means " strength," is a famous one in ancient Indian history, and recurs in all sorts of forms and places. In Amritsar they say they came from Ballamgarh, and do not inter-marry with the Dhillon.

- Balagan (बलगन), a tribe of Jats, claiming to be Jammu Rajputs by descent from their eponym. Found in Sialkot.

- Balahar (बलाहर), in Gurgaon the balahar (in Sirsa he is called daura,) is a village menial who shows travellers the way, carries messages and letters, and summons people when wanted by the headmen. In Karnal he is, called lehbar† ; but is not a recognised menial and any one can perform his duties on occasion. In Sirsa, Gurgaon and Karnal he is almost always a Chuhra, cf. Batwal.

- Balahi (बलाही), Balai (बलाई), cf. (Balahar). — In Delhi and Hissar a chaukidar or watchman : in Sirsa a Chamar employed to manure fields, or who takes to syce's and general work, is so termed.

- Balbir (बलबीर), a sept of Kanets which migrated from Chittor in Rajasthan with the founders of Keonthal and settled in the latter State. The founders of Keonthal were also accompanied by a Chaik, a Salathi and a Pakrot, all Brahmans, a Chhibar Kanet, a blacksmith and a turi and the descendants of all these are still settled in the State or in its employ.

- Balfarosh (बलफरोश), a synonym for Bhat (Rawalpindi).

- Bali (बाली), a section of the Muhials (Brahmans) : corr. to the Dhannapotras of the South-West Punjab.

- Balka (बलका), an agricultural clan found in Shahpur: balka in the east of the Punjab is used as equivalent to chela, for ' the disciple of a 'faqlr.'

- * There is said to be a sept of the Baloch of this name in Bahawalpur and Muzaffargarhi on both sides of the Panjnad.

- † Or rehbar, probably from rahbar, 'guide'. In Karnal is no Balahar caste, the term being applied to a sweeper who does this particular kind of corvee— which no one but a sweeper (or in default a Dhanank) will perform.

- Balmiki (बाल्मीकी), Valmiki (वाल्मीकी). — The sect of the Chuhras, synonymous with Balashahi and Lalbegi, so called from Balmik, Balrikh or Bala Shah, possibly the same as the author of the Ramayana* Balmik, the poet, was a man of low extraction, and legend represents him as a low-caste hunter of the Nardak in Karnal, or a Bhil highway-man converted by a saint whom he was about to rob. One legend makes him a sweeper in the heavenly courts, another as living in austerity at Ghazni. See under Lalbegi.

Baloch

The term Baloch is used in several different wavs. By travellers and historians it is employed to denote (i) the race known to them-selves and their neighbours as the Baloch, and [ii] in an extended sense as including all the the races inhabiting the great geographical area shown on our maps as Balichistan. In the latter sense it comprises the Brahuis, a tribe which is certainly not of Baloch origin. In the former sense it includes all the Baloch tribes, whether found in Persia on the west or the Puniab on the east, which can claim a descent, more or less pure, from Baloch ancestors. Two special uses of the term also require notice. In the great jungles below Thanesar - in the Karnal district is settled a criminal tribe, almost certainly of Baloch extraction, which will be noticed below page 55.† Secondly, throughout the Punjab, except in the extreme west and the extreme east, the term Baloch denotes any Muhammadan camel-man. Throughout the upper grazing grounds of the Western Plains the Baloch settlers have taken to the grazing and breeding of camels rather than to husbandry; and thus the word Baloch has become associated with the care of camels, insomuch that in the greater part of the Punjab, the word Baloch is used for any Musalman camel-man whatever be his caste, every Baloch being supposed to be a camel-man and every Muhammadan camel-man to be a Baloch,

Pnttinger and Khanikoff claimed for the Baloch race a Turkoman origin, and Sir T. Holdich and others an Arab descent. Bellew assigned them Rajput descent on very inadequate philological grounds, while Burton, Lassen and others have maintained that they are, at least in the mass, of Iranian race. This last theory is supported by Mr. Longworth Dames who shows that the Baloch came into the present locations in Mekran and on the Indian border from parts of the Iranian plateau further to the west and north, bringing with them a language of the Old Persian stock, with many features derived from the Zend or Old Bactrian rather than the Western Persian.

Dames assigns the first mention of the Baloch in history to the Arabic chronicles of the 10th century A. D., but Firdausi (c. 400 A.H.) refers to a still earlier period, and in his Shah-nama†† the Baloches are described as forming part of the armies of Kai Kaus

- * Temple (in Legends of the Punjab, I, p. 529) accepts this tradtion and says Balmiki is the same as Bala Shah or Nuri Shah Bala, but assigns to him 'the place next to Lal Beg.'

- † This group is also found in Ambala, and the Giloi Baloch of Lyallpur are also said to be an offshoot of it.

- †† So Dames, but the text of the Shah-nama is very corrupt, and the reading Khoch "crest " cannot be relied upon implicit.

and Kai Khusrao. The poem says that the army of Ashkash was from the wanderers of the Koch and Baloch, intent on war, with exalted coekscomb crests, whose back none in the world ever saw. Under Naushirwan, the Cosroes who fought against Justinian, the Baloch are again mentioned as mountaineers who raided his kingdom and had to be exterminated, though later on we find them serving in Naushirwan's own army. In these passages their association with the men of Gil and Dailam (the peoples of Gilan and Adharbaijan) would appear to locate the Baloch in a province north of Karman towards the Caspian Sea.

However this may be, the commencement of the 4th century of the Hijra and of the 10th A.D. finds the Balus or Baloch established in Karman, with, if Masudi can be trusted, the Qufs (Koch) and the Zutt (Jatts). The Baloch are then described as holding the desert plains south of the mountains and towards Makran and the sea, but they appear in reality to have infested the desert now known as the Lut, which lies north and east of Karman and separates it from Khorasan and Sistan. Thence they crossed the desert into the two last-named provinces, and two districts of Sistan were in Istakhri's time known as Baloch country.* Baloch raiders plundered Mahmud of Ghazhni's ambassador between Tabbas and Khabis, and in revenge his son Masud defeated them at the latter place, which lies at the foot of the Karman Mountains on the edge of the desert.

About this time Firdausi wrote and soon after it the Baloch must have migrated bodily from Karman into Mekran and the Sindh frontier, after a partial and temporary halt in Sistan. With great probability Dames conjectures that at this period two movements of the Baloch took place : the first, corresponding with the Saljuq invasion and the overthrow of the Dailami and Ghaznawi power in Persia, being their abandonment of Karman and settlement in Sistan and Western Makran ; while the second, towards Eastern Makran and the Sindh border, was contemporaneous with Changiz Khan's invasion and the wanderings of Jalal-ud-Din in Makran.

To this second movement the Baloch owed their opportunity of invading the Indus valley; and thence, in their third and last migration, a great portion of the race was precipitated into the Punjab plains.

It is now possible to connect the traditional history of the Baloch themselves, as told in their ancient heroic ballads, with the above account. Like other Muhammadan races, the Baloch claim Arabian extraction, asserting that they are descended from Mir Hamza, an uncle of the Prophet, and from a fairy (pari). They consistently place their first settlement in Halab (Aleppo), where they remained until, siding with the sons of Ali and taking part in the battle of Karbala, they were expelled by Yazid, the second of the Omayyad Caliphs, in 680 A.D. Thence they fled, first to Karman, and eventually

- * Their settlements may indeed have extended into Khorasan. Even at the present day there is a considerable Baloch population as far north as Turbat-i-Haidari (Curzon's Persia, 1892, i, p. 203),

to Sistan where they wore hospitably received by Shams-ud-Din,* ruler of that country. His successor, Badr-ud-Din, demanded, according to eastern usage, a bride from each of the 44 bolaks or clans of the Baloch. But the Baloch race had never yet paid tribute in this form to any ruler, and they sent therefore 44 bovs dressed in girls' clothes and fled before the deception could be discovered. Badr-ud-Din sent the boys back but pursued the Baloch, who had fled south-eastwards, into Kech-Makran where he was defeated at their hands.

At this period Mir Jalal Khan, son of Jiand, was ruler of all the Baloch. He left four sons, Rind, Lashar, Hot and Korai from whom are descended the Rind, Lashari, Hot and Korai tribes ; and a son-in-law, Murad, from whom are descended the Jatoi† or children of Jato, Jalal Khan's daughter. Unfortunately, however, certain tribes cannot be brought into any of these five, and in order to provide them with ancestors two more sons, Ali and Bulo, ancestor of the Buledhi, have had to be found for Jalal Khan. From Ali's two sons, Ghazan and Umar, are descended the Ghazani, Harris and the scattered Umranis.

Tradition avers that Jalal Khan had appointed Rind to the phagh or turban of chiefship, but that Hot refused to join him in creating the asrokh or memorial canopy to their father. 'Thereupon each performed that ceremony separately and thus there were five asrokhs in Kech.' But it is far more probable that five principal gatherings of clans were formed under well-known leaders, each of which became known by some nickname or epithet, such as rind "cheat," hot, "warrior," Lashari, " men of Lashar" and, later, Buledhi, " men of Boleda." To these other clans became in the course of time affiliated.

A typical example of an affiliated clan is afforded by the Dodai, a clan of Jat race whose origin is thus described : —

Doda†† Sumra, expelled from Thatha by his brethren, escaped by swimming his mare across the Indus, and, half frozen, reached the hut of Salhe, a Rind. To revive him Salhe placed him under the blankets with his daughter Muaho, whom he eventually married. " For the woman's sake," says the proverb, " the man became a Baloch who had been a Jatt, a Jaghdal, a nobody; he dwelt at Harrand under the hills, and fate made him chief of all." Thus Doda; founded the great Dodai tribe of the Baloch, and Gorish, his son, founded the Gorshani or Gurchdni, now the principal tribe of Dodai origin. The great Mirrani tribe, which for 200 years gave chiefs to Dera Ghazi Khan, was also of Dodai origin.

- * According to Dames there was a Shams-ud-Din, independent malik of Sistan, who claimed descent from the Saffaris of Persia and who died in 1104 A.D. ;559 H.) or nearly 500 years after the Baloch migration from Aleppo. Badr-ud-Uin appears to be unknown to history.

- † It is suggested that Jatoi or 'husband of a Jat woman,' just as bahnoi means ' husband of a sister,' although in Jatoi the 't' is soft.

- †† Doda, a common name among the Sumras whose dynasty ruled Sindh until it was overthrown by the Sammas. About 1250 A.D. or before that year we find Baloch adventurers first allied with the Sodhas and Jharejas, and then supporting Doda IV, Sumra, Under Umar, his successor, the Baloches are found combining with the Sammas, Sodhas and Jatts, (Jharejas), but were eventually forced back to the hills without effecting any permanent lodgment in the plains.

After the overthrow of the Sumras of Sindh nothing is heard of the Baloch for 150 years and then in the reign of Jam Tughlaq, the Samma (1423 — 50), they are recorded as raiding near Bhakhar in Sindh. Doubtless, as Dames holds, Taimur's invasion of 1399 led indirectly to this new movement. The Delhi empire was at its weakest and Taimur's descendants claimed a vague suzereignty over it. Probably all the Western Punjab was effectively held by Mughal intendants until the Lodi dynapty was established in 1451. Meanwhile the Langah Rajputs had established themselves on the throne of Multan and Shah Husain Langah (1469 — 1502) called in Baloch mercenaries, granting a jagir, which extended from Kot Karor to Dhankot, to Malik Sohrab Dodai who came to Multan with his sons, Ghazi Khan, Fath Khan and Ismail Khan.*

But the Dodai were, not the only mercenaries of the Langahs. Shah Hussain had conferred the jagirs of Uch and Shor(kot) on two Samma brothers, Jam Bayazid and Jam Ibrahim, between whom and the Dodais a feud arose on Shah Mahmud's accession. The Jams promptly allied themselves with Mir Chakur, a Rind Baloch of Sibi who had also sought service and lands from the Langah ruler and thereby mused the Dodais' jealousy. Mir Chakur is the greatest figure in the heroic poetry of the Baloch, and his history is a. renarkable one. The Rinds were at picturesque but deadly feud with the Lasharis. Gohar, the fair owner of vast herds of camels favoured Chakur, but Gwaharam Lashari also claimed her hand. The rivals agreed to decide their quarrel by a horse race, but the Rinds loosened the girths of Gwahardm's saddle and Chakur won. In revenge the Lasharis killed some of Gohar's camels, and this led to a desperate 30 years' war which ended in Chakur's expulsion from Sibi in spite of aid invoked and received from the Arghun conquerors of Sindh. Mir Chakur was accompanied by many Rinds and by his two sons, Shahzad† and Shaihak, and received in jagir lands near Uch from Jam Bayazid, Samma. Later, however, he is said in the legends to have accompanied Humayun en his re-conquest of India. However this may have been, he undoubtedly founded a military colony of Rinds at Satgarha, in Montgomery, at which place his tomb still exists. Thence he was expelled by Sher Shah, a fact which would explain his joining Humayun.

At this period the Baloch were in great force in the South-West Punjab, probably as mercenaries of the Langah dynasty of Multan, but also as independent freebooters. The Rinds advanced up the Chenab, Ravi and Sutlej valleys; the Dodai and Hots up the Jhelum and Indus. In 1519 Babar found Dodais at Bhera and Khushab and he confirmed Sohrab Khan's three sons in their possession of the country of Sindh. He also gave Ismail Khan, one of Sohrdb's sons, the ancient pargana of Ninduna in the Ghakhar country in exchange for the lands of Shaikh Bayazid Sarwani which he was obliged to surrender. But in 1524 the Arghuns overthrew Shah Mahmad Langah.

- * The founders of the three Dehras, which give its name to the Derajāt. Dera Fath Khan is now a mere village.

- †Shahzad was one of miraculous origin, his mother having been overshadowed by some mysterious power, and a mystical poem in Balochi on the origins of Multan is ascribed to him. Firishta says he first introduced the Shia creed into Multan. a curious statement.

with bis motley host of Baloch, Jat, Rind, Dodai and other tribes, and the greatest confusion reigned.

The Arghuns however submitted to the Mughal emperors, and this appears to have thrown the bulk of the Baloch into opposition to the empire. They rarely entered the imperial service — a fact which is possibly explained by their dislike to serve at a distance from their homes — and under Akbar we read of occasional expeditions against the Baloch. But the Lasharis apparently took service with the Arghuns and aided them against Jam Firoz — indeed legend represents the Laghari as invading Guzerat and on return to Kachhi as obtaining a grant of Gundava from the king.* The Jistanis, a Lashari clan, also established a principality at Mankera in the Sindh-Sagar Doab at this time, but most of the Lasharis remained in Makran or Kachhi. Among the earliest to leave the barren hills of Balochistan were the Chandias who settled in the Chandko or Chanduka tract along the Indus,† in Upper Sind on the Punjab border. The Hots pressed northwards and with the Dodais settled at Dera Ismmail Khan which they held for 200 years. Close to it; the Kulachis founded the town which still bears their name. Both Dera Ismail Khan and Kulachi were eventually conquered by Pathans, but the Kulachis still inhabit the country round the latter town. South of the Jistkanis of Mankera lay the Dodais of the once great Mirrani clan which gave Nawabs to Dera Ghazi Khan till Nadir Shah's time. Further still afield the Mazaris settled in Jhang and are still found at Chatta Bakhsha in that District, The Rinds with some Jatois and Korais are numerous in Multan, Jhang, Montgomery, Shahpur and Muzaffargarh, and in the last-named district the Gopangs and Gurmanis are encountered. All these are descendants of the tribes which followed Mir Chakur and have become assimilated to the Jat tribes with whom in many cases they intermarry. West of the Indus only has the Baloch retained his own language and tribal organization.

In the Derajat and Sulaimans the Baloch are grouped into tumans which cannot be regarded as mere tribes. The tuman is infact a political confederacy, ruled by a tumandar, and comprising men of one tribe, with affliated elements from other tribes not necessarily Baloch. The tumans which now exist as Organisations are the Marri, Bughti, Mazari, Drishak, Tibbi Lund, Sori Lund, Leghari, Khosa, Nutkani, Bozdar, Kasrani, Gurchani and Shambuni. Others, such as the Buledhi, Hasani, Jakrani, Kahiri, are found in the Kachhi territory of Kalat and in Upper Sind, with representatives in Bahawalpur territory.

The Bozdar tuman is probably in part of Rind descent, but the name means simply goat-herd. They live in independent territory in the Sulaimdns, almost entirely north-west of Dera Ghazi Khan.

The Bughti or Zarkani tuman is composed of several elements. Mainly of Rind origin it claims descent from Gyandar, a cousin of Mir Chakur. The Raheja, a clan with an apparently Indian name, is said to have been founded by Raheja, a son of Gyandar. The Nothani

- * The Maghassis, a branch of the Lasharis, are still found in Kachh Gundāva.

- † Chandias are also numerous in Mzafargarh and Dera Ismail Khan.

clan holds the guardianship of Pir Sohri's shrine though they have admitted Gurchani to a share in that office, and before an expedition , each man passes under a yoke of guns or swords held by men of the clan. They can also charm guns so that the bullets shall be harmless,* and claim for these services a share of all crops grown in the Bughti country.

The Shambanis, who form a sub-tuman, but are sometimes classed as an independent tuman, trace their descent to Rihan, a cousin of Mir Chakur, and occupy the hill country adjacent to the Bughti and Mazari tumans. The Bughti occupy the angle of the Sulaiman Mountains between the Indus and Kachhi and have their head-quarters at Syahaf (also called Dera Bibrak or Bughti Dera).

The Buledhi or Burdi tuman derives its name from Boleda in Makran and was long the ruling race till ousted by the Gichki. It is also found in the Burdika tract on the Indus, in Upper Sindh and in Kachhi.

The Drishak tuman is said to be descended from one of Mir Chakur's companions who was nicknanied Drishak or 'strong' because he held up a roof that threatened to crush some Lashari women captives, but it is possibly connected with Dizak in Makran. Its head-quarters are at Asni in Dera Ghazi Khan.

The Gurchani tuman is mainly Dodai by origin, but the Syahphad Durkani are Rinds; as are probably the Pitafi, Jogani, and Chang clans — at least in part. The Jistkanis and Lasharis (except the Gabol† and Bhand sections) are Lasharis, while the Suhriani and Holawani are Bulethis. The Gurchani head-quarters are at Lalgarh near Harrand in Dera Ghazi Khan.

Kasrani†† (so pronounced, but sometimes written Qaisarani as descended from Qaisar) is a tuman of Rind descent and is the most northerly of all the organised tumans, occupying part of the Sulaimans and the adjacent plains in Deras Ghazi Khan (and formerly, but not now), Ismail Khan.

The Khosas form two great tumans,§ one near Jacobabad in Upper Sindh, the other with its head- quarters at Batil near Dera Ghazi Khan. They are said to be mainly of Hot descent, but in Dera Ghazi Khan the Isani clan is Khetran by origin, and the small Jajela clan are probably aborigines of the Jaj valley which they inhabit.

The Legrhari tuman derives its origin from Kohphrosh, a Rind, nicknamed Leghar or 'dirty.' But the tuman also includes a Chandia clan and the Haddiani and Kaloi, the sub-tuman of the mountains, are said to be of Bozdar origin. Its head-quarters are at Choti in Dera Ghazi Khan, but it is also found in Sindh.

- * The following Baloch septs can stop bleeding by charms and touching the wounds, and used also to have the power of bewitching the arms of their enemies : — The Bajani sept of the Durkani, the Jabrani sept of the Lashari, and the Girani sept of the Jaskani ; among the Gurchanis : the Shahmani sept of the Hadiani Legharis, and, among the Khosas, the Chitar and Faqirs.

- † A servile tribe, now of small importance, found mainly in Muzaffargarh.

- †† The Qasranis practise divination from the shoulder-blades of sheep (an old Mughal custom) and also take auguries from the flight of birds.

The Lunds form two tumans, one of Sori, with its head -quarters at Kot Kandiwala, the other at Tibbi, both in Dera Ghazi Khan. Both claim descent- from Ali, son of Rihan, Mir Chakur's cousin. The Son Lunds include a Gurchani clan and form a large tuman, living in the plains, but the Tibbi Lunds are a small tuman to which are affiliated a clan of Khosas and one of Rinds — the latter of impure descent.

The Marri tuman, notorious for its marauding habits which necessitated an expedition against it only in 1880, is of composite origin.

The Ghazani section claims descent from Ghazan, son of Ali, son of Jalal Khan and the Bijaranis from Bijar Phuzh* who revolted against Mir Chakur. The latter probably includes some Pathan elements. The Mazaranis are said to be Khetrans, and the Loharanis of mixed blood, while Jatt, Kalmati, Buledhi and Hasani elements have doubtless been also absorbed.

The Mazaris are an organised clan of importance, with head-quarters at Rojhan in Dera Ghazi Khan. Its ruling sept, the Balachani, is said to be Hot by descent, but the rest of the tribe are Rinds. The name is derived apparently from mazar, a tiger, like the Pathan 'Mzarai.'

The Kirds or Kurds, a powerful Brahui tribe, also furnish a clan to the Mazaris. The Mazaris as a body (excluding the Balachanis) are designated Syah-laf, or 'Black-bellies.'

Other noteworthy tribes, not organized as tumans, are —

The Ahmdanis† ofMana, in Dera Ghazi Khan. They claim descent from Gyandar and were formerly of importance.

The Gishkauris, found scattered in Dera Ismail Khan, Muzaffargarh and Mekran, and claiming descent from one of Mir Chukur's Rind companions, nick-named Gishkhaur, But the Gishkhaur is really a torrent in the Boleda Valley, Mekran, and possibly the clan is of common descent with the Buledhi.††

Talpur or Talbur, a clan of the Leghdris, is, by some, derived from its eponym, a son of Bulo, and thus of Buledhi origin. Its principal representatives are the Mirs of Khairpur in Sind, but a few Talpurs are still found in Dera Ghazi Khan. Talbur literally means 'wood-cutter' (fr. tāl, branch, and buragh, to cut).

The Pitafis, a clan found in considerable numbers in [[Dera Ismail Khan]] and Muzaffargarh§. Pitafi would appear to mean 'Southern.'

The Nutkani or Nodhakani, a compact tribe, organized till quite recently as a tuman, and found in Sangarh, Dera Ghazi Khan District.

The Mashori, an impure clan, now found mainly in Muzaffargarh.‖

The Mastoi, probably a servile tribe, found principally in [[Dera Ghazi Khzn]] where it has no social status.

- * The Phuzh are or were a clan of Rinds, once of great importance --indeed the whole Rind tribe is said to have once been called Phuzh. They are now only found at Kolanah in Mekran, in Kachhi and near the Bolan Pass. ui

- †Large Ahmdani clans are also found among the Lunds of Sori and the Haddiani Leghanis.

- †† The Lashari sub-tuman of the Gurohani also includes a Gishkhauri sept, and the Dombkis nave a clan of that name.

- § Also as a Gurchani clan in Dera Ghazi Khan. The Bughtis have a Masori clan.

The Dashti, another servile tribe, now found scattered in small numbers iu Dera Ismail Khan and Dera Ghazi Khan, in Muzaffargarh and Bahawalpur.

The Gopang, or more correctly Gophank [ic. gophanh, 'cowherd'), also a servile tribe, now scattered over Kachhi, Dera Ismail Khan, Multan and Muzaffargarh, especially the latter.

The Hot (Hut) once a very powerful tribe (still so in Mekran) and widely spread wherever Baloches are found, but most numerous in Dera Ismail Khan, Muzaffargarh, Jhang and Multan.

The Jatoi, not now an organized tribe, but found wherever Baloches have spread, i.e., in all the Districts of the South-West Punjab and as far as Jhang, Shahpur and Lahore.

The Korai or Kaudai, not now an organized tuman, but found wherever Baloches have spread, especially in Dera Ismail Khan, Multan and Muzaffargarh.

The history of the Baloch is an instructive illustration of the transformations to which tribes or tribal confederacies are prone. The earliest record of their organisation represents them as divided into 44 bolaks of which 4 were servile.

But as soon as history begins we find the Baloch nation split up into 5 main divisions, Rind, Lashari, Hot, Korai (all of undoubted Baloch descent) and Jatoi which tradition would appear to represent as descended from a Baloch woman (Jato) and her cousin (Murad). Outside these groups are those formed or affiliated in Mekran, such as the Buledhis, Ghazanis and Umaranis. Then comes the Doadi tribe, frankly of non-Baloch descent in the male line. Lastly to all these must be added the servile tribes, Gopangs, Dashtis, Gholas and others. In a fragment of an old ballad is a list of servile tribes, said to have been gifted by Mir Chakur to Bānari, his sister, as her dower and set free by her :

' The Kirds, Gabols, Gadahis, Talburs and the Marris of Kahan — all were Chakur's slaves.'

Other versions add the Pachalo (now unknown) and 'the rotten-boned Bozdars.' Other miscellaneous stocks have been fused with the Baloch — such as Pathans, Khetrans, Jatts.

Not one single tribe of all those specified above now forms a tuman or even gives its name to a tuman. We still find the five main divisions existing and numerous, but not one forms an organised tuman. All five are more or less scattered or at least broken up among the various tumans. The very name of bolak is forgotten — except by a clan of the Rind Baloch near Sibi which is still styled the Ghulam (slave) bolac. Among the Marris the clans are now called takar (cf. Sindhi takara, mountain), the septs phalli, and the smaller sub-divisions phara. The tuman (fr. Turkish tūmān, 10,000) reminds us of the Mughal hazara, or region, and is a semi-political, semi-military confederacy.

Tribal nomenclature among the Baloch offers some points of interest. As already mentioned the old main divisions each bore a significant name. The more modern tribes have also names which occasionally look like descriptive nick-names or titles. Thus Lund (Pers.) mean

knave, debauchee or wanderer, just as Rind does : Khosa (Sindhi) means robber (and also 'fever'): Marri in Sindhi also chances to mean a plague or epidemic. Some of the clan-names also have a doubtfull totemistic meaning : e.g., Syah-phadh, Black-feet : (gul-phadh, flower-feet (a Drishak clan) : (ganda-gwalagh, small red ant, (a Durkani clan) Kalphur, an aromatic plant, Glinus lotoides (a Bughti clan).

Custom, not the Muhammadan Law prevails among the Baloch as a body but the Nutkanis profess to follow the latter and to a large extent do in fact give effect to its provisions. Baloch often postpone a girl's betrothal till she is 16 years of age, and have a distinctive observance called the hiski,† which consists in Casting a red cloth over the girl's head, either at her own house or at some place agreed upon by the kinsmen. Well-to-do people slaughter a sheep or goat for a feast; the poorer Balocti simply distribute sweets to their guests. Betrothal is considered almost as binding as marriage, especially in Rajanpur tahsil, and only impotence, leprosy or apostasy will justify its breach. Baloch women are not given to any one outside the race, save to Shyyids, but a man may marry any Muhammadan woman, Baloch, Jat or even Pathan, but not of course Savyid. The usual practice is to marry within the sept, women being sold out of it if they go astray. Only some sections of the Nutkanis admit an adult woman's right to arrange her own marriage ; but such a marriage, if effected without her guardian's consent, is considered 'black' by all other Baloch. Public feeling demands strong grounds for divorce, and in the Jampur tahsil it is not customary, while unchastity is the only recognised ground in Rajanpur. Marriage is nearly always according to the orthodox Muhammadan ritual, but a form called tan-bakhshi (' giving of the person ') is also recognised. It consists in the woman's mere declaration that she has given herself to her husband, and is virtually only used in the case of widows. The rule of succession is equal division among the sons, except in the families of the Mazari and Drishak chiefs in which tho eldest son gets a some- what larger share than his brothers. Usually a grandson got no share in the presence of a father's brother, but the custom now universally recognised is that grandsons get their deceased fathers' share,†† but even now in Sangarh the right of representation is not fully recognised, for among the Baloch of that tahsil grandsons take per capita, if there are no sons. As a rule a widow gets a life interest in her husband's estate, but the Gurchanis in Jampur refuse to allow a woman to inherit under any circumstances. Daughters rarely succeed in the presence of male descendants of the deceased's grandfather equally remote, the Baloch of Rajanpur and Jampur excluding the daughter by her father's cousin and nearer agnates ; but in Sangarh tahsil daughters get a share according to Muhammadan Law, provided they

- * From Mr. A. H Diack's Customary Law of ihe Dera Qhdzi Khan District, Vol. xvi of the Punjab Customary Law Series.

- †The hiski is falling into disuse in the northernmost tahsil of Dera Ghazi Khan and among the Gopang along the Indus in Jampur.

- †† A few Nutkani sections in Sangarh still say that they only do so if it is formally bequeathed to them by will.

do not make an unlawful marriaore.* Where the daughter inherits her right is not extinguished by her marriage, but the Baloch in Rajanpur tahsil insist, that if married she shall have married within her father's phalli, or if unmarried shall marry within it, as a condition of her succession. The resilient son-in-law acquires no special rights, but the daughter's son in Jampur and Rajanpur succeeds where his mother would succeed. No other Baloch appear to recognise his right. When brother succeeds brother the whole blood excludes the half in Sangarh and Dera Ghazi Khan tahsils, but in Jampur and Rajanpur all the brothers succeed equally. Similarly, in Sangarh, the associated brothers take half and the others the remaining half. Sisters never succeed (except in those few sections of the Nutkani]]s of Sangarh which follow Muhammadan law). A step-son has no rights of succession, but may keep what his step-father gives him during his life-time, and, in Sangarh and Rajanpur, may get one-third of a natural son's share by will. Adoption is not recognised, except possibly among the Baloch of Sangarh, and those of Rajanpur expressly forbid it. But adoption in the strict Hindu sense is quite unknown, since a boy can be adopted even if the adoptor has a son of his own, and any one can adopt or be adopted. In Sangarh, again, a widow may adopt, but only with the consent of her husband's kinsmen. The adopted son retains all his rights in his natural father's property, but in Sangarh he does not succeed his adoptive father if the latter have a son born to him after the adoption (a rule curiously inconsistent with that which allows a man to adopt a second son). Except in Jampur tahsil, a man may make a gift of the whole of his land to an heir to the exclusion of the rest, and as a rule he may also gift to his daughter, her husband or son and to his sister and her children, but the Lunds and Legharis would limit the gift to a small part of the land. Gifts to a non-relative are as a rule invalid, unless it be for religion, and even then in Jampur it should only be of part of the estate. Death-bed gifts are invalid in Sangarh and Jampur and only valid in the other two tahsils of Dera Ghazi Khan to the extent allowed by Muhammadan Law. Sons cannot enforce a partition, but in Sangarh their consent is necessary to it ; yet in that and the Dera Ghazi Khan tahsils it is averred that a father can make an unequal partition (and even exclude a son from his share) to endure beyond his life-time. But in Jampur and Rajanpur the sons are entitled to equal shares, the Mazari and Drishak chiefs excepted. The subsequent birth of a son necessitates a fresh partition. Thus among the Baloch tribes we find no system of tribal law, but a mass of varying local usuage. Primitive custom is ordinarily enforced, and though the semi-sacred Nutkanis in Sangarh tahsil consider it incumbent upon them to follow Muhammadan Law, even they to do not give practical effect to all its niceties.

Birth customs. The usual Muhammadan observances at birth are in vogue. The hang is sounded into the child's ear by the mullah six days after its birth and on the 6th night a sheep or cattle are slaughtered and the brotherhood invited to a feast and dance. The child

- * But the Khosas and Kasranis in this tahsil do not allow daughters to succeed at all, unless their father bequeath them a share, and that share must not exceed the share admissible under Muhammadan Law.

is also named on this occasion. If a boy it is given its grandfather's name, if he be dead ; or its father's name if he is dead: so too an uncle's name is given if both fther his grandfather be alive, (common name's are Dadu, Bangul, Kambir, Thaga (fr. thagagh, to be long lived), Drihan.

Circumcision (shade, tahor) is performed at the age of 1 or 2, by a tahorokh. or circumcisor who is a Domb, not a mullah or a Pirhain, except in the plains where a Pirhain is employed. In the hills a Baloch can act if no Domb be available. Ten or twelve men bring a ram and slaughter it for a feast, to which the boy's father (who is called the tahor wzha*) contributes bread, in the evening : next morning he entertains the visitors and they depart. In the plains cattle are slaughtered and the brotherhood invited; nendr being also given — a usage not in vogue in the hills.

Jhand, the first tonsure, is performed, prior to the circumcision, at the shrine of Sakhi Sarwar, the weight of the child's hair in silver being given to its mujawars.

Divorce (called sawan as well as tilāk) is effected in the hills by casting stones 7 times or thrice and dismissing the wife.

Concubinage is not unusual, and concubines are called suret, but winzas are not known, it is said. The children by such women are called suretwal and receive no share in their father's land, but only maintenance during his life-time. These surets appear, however, to hold a better position than the molid or slave women.

Terms of kinship. The kin generally are called shād or brathari (brotherhood), brahmdagh.

Pith-phiru, fore-fathers.

Table ?

The mother's brother is māma as in Punjabi, but her sister is tri and her son tri-zākht.

In addressing relatives other words are used, such as abba, father; adda (fem.-i), brother (familiarly). A wife is uually zāl, also āmrish.

A step-son is patrāk, pazādagh or phizādngh (fr. phadha, behind, thus corresponding to the Punjabi pichhalag). A step daughter is nafuskh.¶

- * Wazha = Khwaja or master. The father is 'lord of the tahor or purification,'

- † It will be observed that nashār = son's or brother's wife

- †† Dakhun or dahun also appears to mean brother's wife.

- § tri thus equals mother's sister or father's brothers wife.

- ‖ Barāthar is a poetical form.

- ¶ Dames' Monograph, p. 25,

A namesake is amnam and a contemporary amsan. Equally simple are the Baloch marriage customs. The youth gives shawls to his betrothed's mother and her sisters, and supplies the girl herself with clothes till the wedding. Before that occurs minstrels (doms) are sent out to summon the guests, and when assembled they make gifts of money or clothes to the bridegroom. Characteristically the latter's hospitality takes the form of prizes— a camel for the best horse, money to the best shot and a turban to the best runner. The actual wedding takes place in the evening, Nendr* or wedding gifts, the neota or tambol of the Punjab, are only made in the plains, but among the hill Baloch a poor man goes the round of his section and begs gifts, chiefly made in cash. Similarly the tribal chiefs and headmen used to levy benevolences, a cow from every herd, a sheep from every flock, or a rupee from a man who owned no cattle, when celebrating a wedding. It is also customary to knock the heads of the pair together twice and a relation of them ties together the corners of their chadars (shawls).

A corpse is buried at once, with no formalities, save that a mullah, if present, reads the janaza. Dry brushwood is heaped over the grave.

Three or four days later the āsrokh† or sehā takes place. This appears to be a contribution also called pathar or mhanna, each neighbour and clansman of the deceased's section visiting his relations to condole with them and making them a present of four annas each. In the evening the relations provide them with food and they depart.

On a chief's death the whole clan assembles to present gifts which vary in amount from four annas to two rupees. Six months after- wards the people all re-assemble at the grave, the brushwood is removed and the grave marked out with white stones.

Of the pre-Islamic faith of the Baloch hardly a trace remains. Possibly in Nodh-bandagh (lit. the cloud-binder), surnamed the Gold-scatterer, who had vowed never to reject a request and never to touch money with his hands, an echo of some old mythology survives, but in Baloch legend he is the father of Gwaharam, Chakur's rival for the hand of Gohar. Yet Chakur the Rind when defeated by the Lasharis is saved by their own chief Nodh-bandagh, and mounted on his mare Phul (' Flower').

The Baloch is as simple in his religion as in all else and fanaticism is foreign to his nature. Among the hill Baloch mullahs are rarely found and the Muhammadan fasts and prayers used to be hardly known. Orthodox observances are now more usual and the Quran is held in great respect. Faqirs also are seldom met with and Sayyids are

- * Also called mhanna, lit. 'contributions.'

- † See Doie, Bilochi noma, pp 64-65. But Dames (The Baloch Race, p. 37) translates asrokh by memorial canopy, apparently with good reason. Capt. Coldstream says : 'Asrokh is a ceremony which takes place on a certain day after a death The friends of the deceased assemble at his house and his heirs entertain them and prayers are repeated. The ceremony of dastarbandi or tying a pagri on the head of the deceased's heir is then performed by his leading relative in presence of the guests. The date varies among the different tumans. In Dera Ghazi Khan it is generally the 3rd day after the death : in Balochistan there is apparently no fixed day, but as a rule the period is longer,'

unknown.* The Baloch of the plains are however much more religious outwardly, and among them Sayyids possess considerable influence over their murids.

The Bugtis especially affect Pir Sohri ('the red saint') a Pirozani of the Nodhani† section. This pir was a goat-herd who gave his only goat to the Four Friends of God and in return they miraculously filled his fold with goats and gave him a staff wherewith if smitten the earth would bring forth water. Most of the goats thus given were red (i.e., brown), but some were white with red ears. Sohri was slain by some Buledhis who drove off his goats, but he came to life again and pursued them. Even though they cutoff his head he demanded his goats which they restored to him. Sohri returned home headless and before he died bade his sons tie his body on a camel and make his tomb wherever it rested. At four different places where there were kahir trees it halted, and these trees are still there. Then it rested at the spot where Sohri's tomb now is, and close by they buried his daughter who had died that very day, but it moved itself in another direction. Most Baloches offer a red goat at Sohri's tomb and it is slaughtered by the attendants of the shrine, the flesh being distributed to all who are present there.

Another curious legend is that of the prophet Dris (fr. Arab. Idris) who by a faqir's sarcastic blessing obtained 40 sons at a birth. Of these he exposed 39 in the wilderness and the legend describes how they survived him, and so terrified the people that public opinion compelled Dris to bring them back to his home. But the Angel of Death bore them all away at one time. Dris, with his wife then migrates to a strange land but is false'y accused of slaying the king's son. Mutilated and cast forth to die he is tended by a potter whose slave he becomes. The king's daughter sees him, blind and without feet or hands, yet she falls in love with him and insists on marrying him. Dris is then healed by Health, Fortune and Wisdom and returning home finds his 40 sons still alive! At last like Enoch he attains to the presence of God without dying.††

It must not however be imagined that the Baloch is superstitious. His nervous, imaginative temperament makes him singularly credulous as to the presence of sprites and hobgoblins in desert place, but he is on the whole singularly free from irrational beliefs. His Muhammadanism is not at all bigoted and is strongly tinged with Shiaism its mysticism appealing vividly to his imagination. "All the poets give vivid descriptions 6l the Day of Judgment, the terrors of Hell and the joys of Paradise, mentioning the classes of men who will receive rewards or punishments. The greatest virtue is generosity, the crime demanding most severe punishment is avarice," a law in entire accord with the Baloch code. One of the most characteristic of Baloch legends is the Prophet's Maraj or Ascension, a qnaintlv beautiful narrative in anthropomorphic form § some of the legends current

- * There are a considerable number of Sayyids among the Bozdars.

- † More correctly Nodhakani, descendants of Nodhak, a diminutive of nodh. 'cloud ' a common proper name among the Baloch. The word is corrupted to Nutkani by outsiders.

- †† For the full version see The Baloch Race, pp. 169— 175 where the legend of the Chihil. Tan ziarat is also given. That shrine is held in special reverence by the Brahuis

- § It is given in Dames' Popular Poetry of the Baloches, pp. 157 — 161.

concerning Ali would appear to be Buddhist in origin, e.g., that of The Pigeon and the Hawk.*

Music is popular among the Baloch, but singing to the dambiro, a four-stringed guitar, and the sarinda, a five-stringed instrument like a banjo, is confined to the Dombs. The Baloch himself uses the nar, a wooden pipe about 30 inches in length, bound round with strips of raw gut. Upon this is played the hung, a kind of droning accompaniment to the singing, the singer himself playing it with one corner of his mouth. The effect is quaint but hardly pleasing, though Dames says that the nar accompaniments are graceful and melodious.

The Magassi Baloch.

The Magassi Baloch who are found in Multan, Muzaffargarh, Dera Ghazi Khan, Mianwali and Jhang,† appear to be a "peculiar people" rather than a tribe.†† As both Sunnis and Shias are found among them they do not form a sect. Most of them in the above Districts are murids or disciples of Mian Nur Ahmad, Abbassi, of Rajanpur in Dera Ghazi Khan, whose grandfather Muhammad girl's shrine is in Mianwali. The Magassis in Balochistan are, however, all disciples of Hazrat Ghaus Bahd-ud-Din of Multan. Like all the murids of the Mian, his Magassi disciples abstain from smoking and from shaving the beard. Magassis will espouse any Muhammadan girl, but never give daughters in marriage outside the group, and strictly abstain from any connection with a sweeper woman, even though she be a convert to Islam. At a wedding all the Magassi who are murids of the Mian assemble at the bride's home a day before the procession and are feasted by her parents. The guests offer prayers § to God and the Mian for the welfare of the married pair. This feast is called shādmāna‖ and

- * ibid. p. 161.

- † The Baloch of Jhang merit some notice. They are divided into following septs:-

- 1 Rind-Madari-Gadi.

- 2 Rind-Laghari.

- 3 Rind-Chandia.

- 4 Rind-Kerni.

- 5 Rind-Gadhi.

- 6 Bhand.

- 7 Almani.

- 8 Gishkauri.

- 9 Gopang.

- 10 Gorah.

- 11 Gurmani.

- 12 Hindrani.

- 13 Hot.

- 14 Jamali.

- 15 Jiskani.

- 16 Jatoi.

- 17 Laghari.

- 18 Lishari.

- 19 Lori.

- 20 Marath.

- 21 Mirrani.

- 22 Miruana.

- 23 Nutkani.

- 24 Parihar.

- 25 Patafi.

- 26 Sabqi.

- 27 Shalobi.

- 28 Galkale.

- 29 Kurai.

- 30 Mangesi, &c

- The Madari-Gadi Rinds will not give brides to the Laghari, Chandia, Kerni and Gadhi Rind septs, from whom they receive them, but all these Baloch will take wives from other Muhammadans except the Sayyids. The Mangesi only smoke with men of their own sept.

- † In Balochistan the Magassi are said to form a tuman under Nawab Qaisar Khan, Magassi, of Jhal Magassi. They say that in the time of Ghazi Khan many of them migrated into the present Sangarh tahsil of Dera Ghazi Khan, but were defeated by Lal Khan, tumandar of the Qasranis and driven across the Indus, where they settled in Nawankot, now in Leiah tahsil. Their settlement is now a ruin, as they were dispersed in the time of the Sikhs, but a headman of Nawankot is still regarded as their sirdar or chief

- § In Multan these prayers are called āzi and are said to be offered when the feast is half eaten.

- ‖ In Leiah a shādmāna is said to be observed on occasions of great joy or sorrow All the members and followers of the " Sarai ' or Abbassi family assemble and first eat meat cooked with salt only and bread containing sugar, the leavings being distributed among the poor after prayers have been recited. Every care is taken to prevent a crow or a dog from touching this food, and those who prepare it often keep the mouth covered up. A shādmāna is performed at the shrines of ancestors. It is a solemn rite and prayers are said in common. A boy is not accepted as a disciple by the Pir until he is circumcised, and until he is so accepted he cannot take part in a shādmāna.

precedes all tte other rites and ceremonies. Contrary to Muhammadan usage a Magassi bridegroom may consummate his marriage on the very first night of the wedding procession and in the house of the bride's father. At a funeral, whether of a male or female, the relatives repeat the four takbirs, if they are Sunnis, but disciples of the Mian recite the janaza of the Shias. Magassis, when they meet one another, or any other murid of the Mian Sahib, shake and kiss each other's hands in token of their hearty love and union.

The Magassi in Leiah are Shias and like all Shias avoid eating the hare. But the following customs appear to be peculiar to the Magassi of this tahsil : When a child is born the water in a cup in stirred with a knife, which is also touched with a bow smeared with horse-dung and given to the child to drink. The sixth night after a male birth is kept as a vigil by both men and women, the latter keeping apart and singing sihra songs, while among the men a mirasi beats his drum. This is called the chhati. On the 14th day the whole brotherhood is invited to assembble, women and all, and the boy is presented to them. The doyen of the kinsman is then asked to swing the child in his cradle, and for this he is given a rupee or a turban. From 14 paos to as many sers of gur and salt are then distributed among the kinsmen, and the boy is taken to the nearest well, the man who works it being given a dole of sugar and bread or flour. This is the rite usually called ghari gharoli, and it ought to be observed on the 14th day, but poor people keep it on the day after the chhati. The tradition is that the chhatti and ghari gharoli observances are kept, because Amir Hamza was borne by the fairies from Arabia to the Caucasus when he was six days old, and so every Baloch boy is carefully guarded on the sixth night after his birth. Amir Hamza was, indeed, brought back on the 14th day, and so on that day the observances are kept after a boy's birth. For this reason too, it is said, the bow is strung ! All wedding rites take place at night, and on the wedding night a couch and bedding supplied by the bridegroom are taken to the bride's house by mirasis, who sing songs on the way, and get a rupee as their fee. The members of the bridegroom's family accompany them. This is called the sejband.

At a funeral five takbirs are recited if the mullah happens to be a Shia, but if he is a Sunni only four are read. The nimaz in use are those of the Shias.

The Baloch of Karnal and Ambala form a criminal community. They say they were driven from their native land in the time of Nadir Shah who adopted severe measures to check their criminal tendencies, but they also say that they were once settled in the Qasur tract near Lahore and were thence expelled owing to their marauding habits. They give a long genealogy of their descent from Abraham and derive it more immediately from Rind, whose descendants, they say, are followers of the Imam Shafi and eat unclean things like the Awans, Qalandars, Madaris and the vagrant Baloch who are known as